Articles Menu

The Alberta government has known for more than a decade that its oilsands policies were setting the stage for today’s price crisis.

In 2007, a government report warned that prices for oilsands bitumen could eventually fall so low that the government’s royalty revenues — critical for its budget — would be at risk.

The province should encourage companies to add value to the bitumen by upgrading and refining it into gasoline or diesel to avoid the coming price plunge, the report said.

The Alberta government and oil industry is in crisis mode because the gap between the price paid for Western Canadian Select — a blend of heavy oil and diluent — and benchmark West Texas Intermediate oils has widened to $40 US a barrel.

Some energy companies have called on the government to impose production cuts to increase prices.

The business case for slowing bitumen production was made by the great Fort McMurray fire of 2015.

The fire resulted in a loss of 1.5 million barrels of heavy oil production over several months. As a result, the price of Western Canadian Select rose from $26.93 to $42.52 per barrel.

Premier Rachel Notley has appointed a three-member commission to considering possible production cuts, something Texas regulators imposedon their oil industry in the 1930s to help it recover from falling prices due to overproduction.

Oilsands crude typically sells at a $15 to $25 discount to light oil such as West Texas Intermediate. It costs more to move through pipelines, as it has to be diluted with a high-cost, gasoline-like product known as condensate. According to a recent government report, it can cost oilsands producers $14 to dilute and move one barrel of bitumen and condensate through a pipeline.

And transforming the sulfur-rich heavy oil into other products is more expensive because its poor quality requires a complex refinery, such as those clustered in the U.S. Midwest and Gulf Coast.

But the growing discount has cost Alberta’s provincial treasury dearly because royalties are based on oil prices.

Earlier this year, an RBC report pegged the loss at $500 million a year, while a more recent study estimates the losses could be as high as $4 billion annually.

While a few oilsands companies such as heavily indebted Cenovus say they are losing money due to the heavy oil discount, others are making record profits and say no market intervention or change is necessary.

The difference is those companies heeded the decade-old warnings and invested in upgraders and refineries to allow them to sell higher-value products.

And the current dramatic price discount has divided oilsands producers into winners and losers.

The winners invested in upgraders and refineries, while the losers are producing more bitumen than their refinery capacity can handle or the market needs.

During Alberta’s so-called bitumen crisis, the three top oilsands producers — Suncor, Husky and Imperial Oil — are posting record profits.

All three firms have succeeded this year because they own upgraders and refineries in Canada or the U.S. Midwest that can process the cheap bitumen or heavy oil into higher value petroleum products.

Imperial Oil, for example, boosted production at its Kearl Mine to 244,000 barrels in the most recent quarter, but refined and added value to that product.

As a result its net income for the quarter doubled to $749 million.

CEO Rich Kruger said that the collapse in bitumen prices was not a concern.

“Looking ahead, in the current challenging upstream price environment, we are uniquely positioned to benefit from widening light crude differentials,” he stated in a press release.

Suncor also reported that most of its 600,000-barrel-a-day production is not subject to the price differential because it upgrades the junk resource into synthetic crude or refines heavy oil into gasoline.

In its most recent business report, Husky reported a 48-per-cent increase in profits as cheap bitumen has fed its refineries and asphalt-making facilities.

The Alberta government knew this was coming.

A technical paper on bitumen pricing for Alberta Energy’s 2007 royalty review warned the province about the perils of increasing production without increasing value-added production.

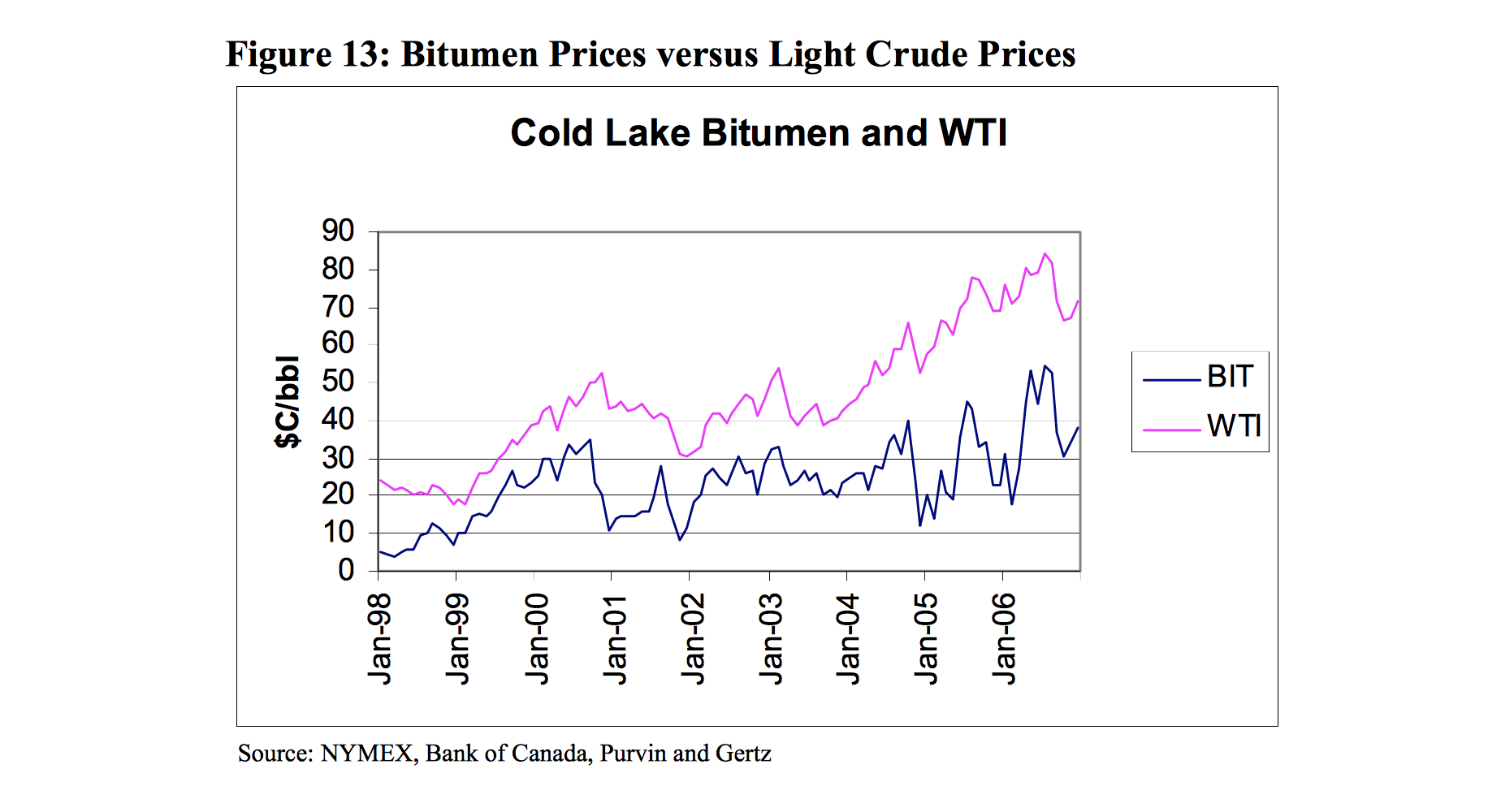

“Bitumen prices, when compared to light crude oil prices, are typified by large dramatic price drops and recoveries,” it noted. Between 1998 and 2005, “bitumen prices were 63 per cent more volatile than West Texas Intermediate prices,” it said.

The analysis added that “for bitumen to attract a good price, it needs refineries with sufficient heavy-oil conversion capacity.”

The province’s push to develop the oilsands quickly increased the risk, the report said. “Price volatility for bitumen, especially the extreme low prices that have been witnessed several times over the past several years, is the most obvious risk.”

And the report noted that increasing bitumen production posed “a revenue risk for the resource owner” — the people of Alberta. When the differential widens, Alberta makes less money on its already low royalty bitumen rates.

Companies can compensate for the price risk by buying or investing in U.S. refineries; securing long-term pipeline contracts; investing in storage or using contracts to protect them from price swings.

Many oilsands producers, including Suncor, Imperial and Husky, have lessened their vulnerability to bitumen’s volatility by doing all of these things.

But the provincial government is more exposed to price swings, the report said.

“For the province, the variety of risk mitigation strategies that can be pursued by industry is generally not available. Therefore Alberta is absorbing a higher share of price risk, particularly where royalty is based on bitumen values.”

In 2007 Pedro Van Meurs, a royalty expert now based in Panama, warned the government that its royalty for bitumen was way too low in a paper titled “Preliminary Fiscal Evaluation of Alberta Oil Sand Terms.”

Van Meurs noted that upgrading considerably enhances the value of bitumen and would generate more revenue for the province.

But that did not appear to be the policy the government was pursuing, warned Van Meurs in his report to the government.

Low royalties “raise the issue whether it is in the interest of Alberta to continue to stimulate through the fiscal system such very high-cost production ventures,” wrote Van Meurs, a chief of petroleum developments for the Canadian government in the 1970s.

Charging higher royalties would not only slow down production and avoid cost overruns in the oilsands but also encourage “upgrading projects with higher value-added opportunities,” he wrote.

But Alberta succumbed to sustained oil patch lobbying in 2007 and ignored Van Meurs’ advice.

As a result oilsands royalties remained low and there was little incentive for companies to add value or build more upgraders and refineries.

In 2009 the province’s energy regulator said in an annual report on supply and demand outlooks that low bitumen prices were a direct consequence of overproduction.

Planned additions for upgrading and refining would resolve the problem in the future.

But after the 2008 financial crisis, planned upgraders in Alberta did not materialize.

With no provincial policy encouraging value-added processing, the industry took a strip-it-and-ship-it approach on bitumen and depended solely on pipelines to deal with overproduction.

Robyn Allan, an independent B.C. economist and former CEO of the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia, says the 2009 report by the energy regulator clearly shows the Alberta government knew the risks of overproduction.

“It won’t matter how many pipelines are built if oil producers continue to increase the amount of low quality product they pump from the oil sands. Pipelines do nothing to improve quality and with new regulations on sulphur content, the world is telling us the downward pressure on heavy oil prices will only get worse,” said Allan.

In 2017, only 43 per cent of the bitumen produced was actually upgraded in Canada while 57 per cent was shipped raw to U.S. refineries.*

According to a Nov. 6 article in the Wall Street Journal, Phillips 66, a major buyer of cheap Canadian bitumen, ran its refineries at 108 per cent of capacity and was “earning an average $23.61 a barrel processed there.” Profits jumped to $1.5 billion, an increase of 81 per cent over last year.

“U.S. refining has really gone from being a dog to being a fairly attractive business model,” one consultant told the Wall Street Journal. “I don’t think that’s going to change any time soon.”

Another beneficiary of Alberta’s no-value added policy has been the billionaire Koch brothers.

They own the Pine Bend refinery in Minnesota, which turns more than 340,000 barrels of Canada’s crude into value-added products every day.

A widening of the price discount of heavy oil by just $15 adds an additional $2 billion in windfall profits a year for Koch Industries, one of the most powerful companies in North America.

The risks of Alberta’s policy of shipping raw bitumen to U.S. refineries was outlined again during the province’s 2015 royalty review, which like the 2007 report, resulted in little change due to successful industry lobbying.

In 2015, Barry Rogers of Edmonton-based Rogers Oil and Gas Consulting warned the government that low royalties for bitumen simply encouraged the industry to export the heavy oil to U.S. refineries with no value added in Canada.

“By not charging a competitive fiscal share Alberta is in fact subsidizing the industry. This gets government directly into the business of business and removes the benefits of market-priced signals — leading to reduced innovation, higher costs, reduced competitiveness, a transfer of economic rent from resource owners to industry and reduced economic diversification.”

Rogers added that the current policy might benefit a few powerful companies but was “a disaster for the overall industry, and, therefore, a disaster for Alberta — both for current and future generations.”

[Photo: In 2007, an Alberta government warned that bitumen prices could eventually fall so low that the government’s royalty revenues — critical for its budget — would be at risk. Photo via Government of Alberta.]