Dec. 10, 2019 [- See article below: "Green New Deal Must Get Real"]

Ben Wray assesses the phenomenon of the Green New Deal. where it comes from and what potential it has.

I’ve spent a few weeks analysing Green New Deal politics across the western world, reading the latest literature and looking at what is working and what isn’t. I’ve also been researching effective social movements of the past that have changed the course of history, trying to understand what are the common themes of all of them which made them powerful. Finally, I’ve been looking at the General Election manifestos of the main political parties in the UK, to get an idea of what they are proposing.

In this piece I am going to summarise my findings, briefly presenting what’s going on with the GND movement, then proposing 10 key do’s and don’t for the movement if it is to progress.

If you feel you have a good working knowledge of Green New Deal politics, you may wish to skip to the section ’10 things the Green New Deal movement should do – and 10 things it shouldn’t’.

The Green New Deal has lift off

It’s remarkable to think that just over one year ago the Green New Deal was a fringe idea that almost no one in the mainstream of politics had heard of, never mind taken seriously. The sea change (no pun intended) since then – where now it is on the lips of leaders across the world – has been driven by a number of factors coming together at once.

The idea took off in the space of a week, which started with the pivotal IPCC report coming out last November on the need to keep warming to 1.5C, and ended with Alexandia Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) speaking ay the Sunrise movement’s occupation of Democratic Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office to make the case for a Green New Deal.

Since then, the idea has taken off like a rocket, spreading across the Atlantic and becoming a staple of climate politics in the western world. The Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion movements have used protest and direct action to give the ideas energy and keep the issue in the news.

From a vague idea towards a concrete goal

Part of the reason for the Green New Deal’s rapid ascendancy was that people knew it meant something big and ambitious, but little more than that. This vagueness was a strength to begin with as a broad coalition of people have been able to project their own approach on to a common idea for climate action. However, if the movement is to continue to progress there is a need to rapidly move to a new phase, where GND promotion and inspiration gives way to concrete plans and demands for implementation.

If this doesn’t happen, the danger is that the phrase becomes an empty vessel devoid of real meaning. Already we’ve seen some leaders and governments disingenuously attach themselves to the slogan, despite their actual policies not matching up to the ambitions of the Green New Deal movement.

A growing body of literature advocating the Green New Deal is clarifying what the term really means, and what it doesn’t. Recent books by Naomi Klein and Ann Pettifor are good examples of an increased intellectual concreteness which is now steering the idea. Think-tank’s like the New Economics Foundation and Common Weal are adding policy meat to the Green New Deal skeleton.

A few common elements can be deciphered from this:

- The Green New Deal is about total economic transformation – not simply changing the energy sector, and not simply greening the system; it is an idea for sustainability and equality for the entire economy.

- The Green New Deal is about a new economic model – Themodel of capitalist development based on what Marx called “accumulation for accumulation’s sake” – the pursuit of profit as the bottom line – on a planet with finite resources is doomed to crisis and collapse. The financial system which has built up around the needs of serving capital accumulation with infinite credit, and the role of the neoliberal state as the protectorate of that financial system, are therefore also incongruous with a sustainable economic system. Green New Deal economics is heterogenous in that there are a number of different approaches, but the common denominator of all of them is a break with the current paradigm of growth and capital accumulation as the bottom line.

- The Green New Deal is about acting where you are, and acting now – As the FT succinctly put it when describing the ethos behind the Green New Deal: “The goal is to make decarbonisation a defining national mission rather than an internationally mandated chore.” GND politics is about collective action for the collective good, especially on the big priority areas like heating and transport. It is not about targets, it is not about plans in the distant future, and it is definitely not about UN summits for the self-aggrandisement of global leaders.

Green New Deal whirlwind tour

To get an idea of where Green New Deal politics is at in different places, here is a quick summary of what’s going on in the US, UK and mainland Europe.

United States: The Green New Deal has become a key part of the Democratic Primary race. It is especially associated with the left of the Democrats, with Bernie Sanders making it central to his election campaign, but it’s a sign of the pressure on the Establishment-wing of the party that Joe Biden, current frontrunner, has also formally backed the idea.

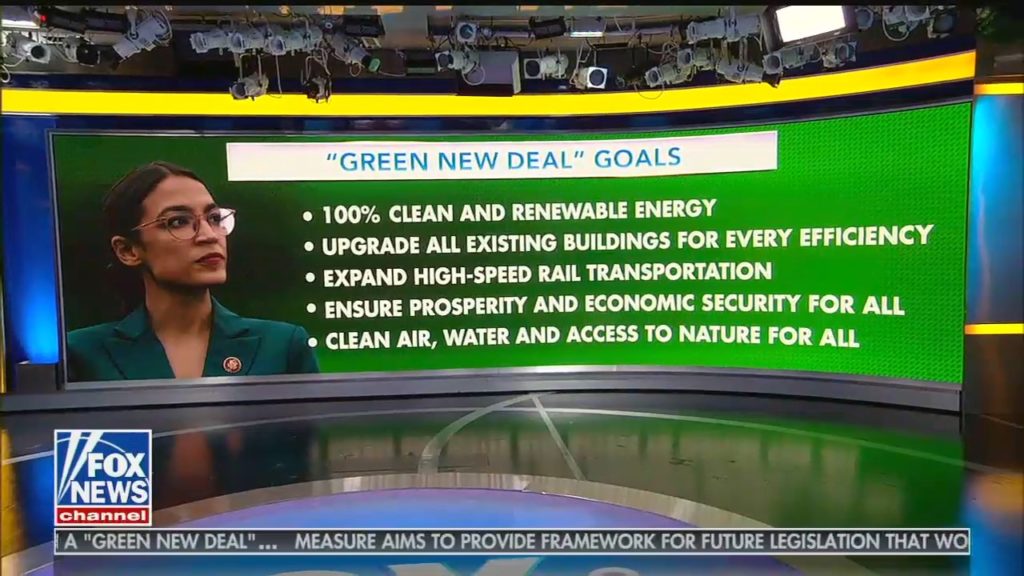

It is also being pursued legislatively, with a resolution put forward by AOC and Ed Markey to the Congress in February. But it’s here that the differences are posed most starkly, with Pelosi welcoming “the enthusiasm” of AOC and Markey’s proposals, but stating: ““I can’t say we’re going to take that and pass it.” Whereas AOC’s plan proposes a 2030 transition to zero-carbon which also includes social measures such as free housing, medical coverage and higher education, Pelosi’s Bill limits itself to trying to get the US to re-commit to the Paris Agreement.

The Democratic Primary will be key to what happens next with the Green New Deal in the US, where the idea has helped re-invigorate socialist politics in in the Democrats, providing it with a new sense of mission and urgency. With Barack Obama warning that the party is moving “too far left”, the trillion-dollar spending associated with the US Green New Deal is the sort of issue that he and other establishment Democrats will be seeking to keep out of the presidential race with the climate-denying Donald Trump – who has said the Green New Deal would “kill millions of jobs” – at the end of 2020.

UK: The Green New Deal is now advocated by all parties on the left to differing degrees.

The Labour Party has made a ‘green industrial revolution’ central to their election manifesto, and are promising a £250 billion ‘Green Transformation Fund’ to finance it, as well as a ‘Just Transition Tax’ on the oil & gas corporations which have contributed most to the UK’s historic carbon emissions, with the money principally being used to fund new jobs for oil & gas workers in the north-east of Scotland. Labour’s plan to nationalise the energy sector could also lay the foundations for a GND.

The SNP backs a GND and is establishing a Scottish National Investment Bank which it says will have as its principal mission financing the zero-carbon transition. However, the commitment’s in the party’s election manifesto do not amount to a Green New Deal in practise, as it prioritises market-based solutions and private sector subsidies. Nicola Sturgeon has also opposed Labour’s Just Transition Tax, saying she believed it would lead to lost jobs in the oil & gas sector.

The Conservatives talk about a “Green Industrial Revolution” in their manifesto and say they will spend more on infrastructure but the biggest spending commitments are on fixing pot-holes in the roads, and under their fiscal rules will not borrow to invest more than 3 per cent of GDP per year, which means they can’t get close to the investment needed for a Green New Deal.

The fossil fuel sector still receives bigger subsidies than renewables in Britain, and, as the absence of the Tories from the climate debate on Channel 4 highlighted, this election is set to be a decisive one for the future of the Green New Deal in Britain.

EU: The European Union as a whole is well behind meeting the terms of the Paris Agreement, with leading states like Germany still locked into coal production until 2038. On Thursday the European Parliament backed a Climate Emergency and set a new target of 55 per cent emissions cut by 2030; still well short of what is required.

The Green New Deal has started to pick up momentum as it has become clear that the EU’s market based mechanisms, like the Emissions Trading Scheme, are woefully inadequate. The GND is posited as an alternative to the current ultra-low public investment environment in the Eurozone, with the currency union’s perverse fiscal rules acting to suppress employment in the Southern European economies in particular.

But while the GND is increasingly talked up across the European left, the mechanism by which it is brought about is divided between pan-European solutions, advocated for instance by Yanis Varoufakis’ DIEM25, and a return to the nation-state, with Jean-Luc Mélenchon among the leading proponents of a radical reform of the Eurozone, and failing that a ‘Plan B’ of unilateral exit. The European Commission is set to unveil a ‘European Green Deal’ plan on 11 December, but an early leaked draft suggests a lack of hard numbers is a concern as to how solid it is, though a commitment to review “the state aid guidelines for environment and energy” is more promising.

The case of the Yellow Vests movement in France shows where green politics can go wrong if it is devoid of a radical agenda and instead seeks to pin the costs on those whose standard of living is already being squeezed. Macron scrapped a wealth tax and replaced it with a tax on fuel to fund green investment. That policy did not last the protests against it and much more, which still rumble on to this day, but in the critique of Emmanuel Macron’s greenwashing and the challenge to inequality, there are commonalities which can be found between the Yellow Vests and GND advocates.

10 things the Green New Deal movement should do – and 10 things it shouldn’t

How do we go forward from here? While every place has its own political conditions to consider, drawing from international experience there are a number of definite do’s and do not’s that activists should consider.

1) Demand performance – not targets

Talk is cheap, and letting politicians talk about climate targets is letting them off the hook. It’s the easiest thing in the world for a leader to talk about an ambitious target in ten or 20 years time as they don’t have to take the tough decision to deliver it. We need to be clear that ambitious targets does not make any nation a ‘world leader’ – only ambitious actions in the here and now can do that.

The Green New Deal movement should not waste one more second talking about targets; we should demand detailed plans for implementation, and exacting timescales to go with those plans. And the start date on the plans must be now.

2) Be collectivist – not individualist

Bernie Sanders slogan ‘not me, us’ should be the slogan of the Green New Deal movement worldwide. We need to imbue political culture with a new collective spirit and sense of common purpose, and the Green New Deal is the perfect idea with which to do that.

There should be no truck with those who would seek to force the movement down the alienating, doomed-to-fail route of individual consumer choices. Not only is that a terrible approach to addressing a collective problem, it’s also morally dubious. We have government to establish a collective set of laws which govern the limits of our individual actions; that’s what it exists for. There’s absolutely no reason why we should all accept the need for laws when it comes to, for instance, food standards and workplace health & safety, but not for ecological sustainability.

3) Be positive – not miserable

I writethis is as someone prone toapocalyptic doom-mongering – it’s not helpful, it’s not appealing and it’s not effective.Everywhere that the Green New Deal is taking off as an idea it is because it is being led by people with a positive story to tell about how not only can we save the world, but we can make all of our lives better in the process.

That’s why while there is a need to reduce global economic output, it is better to couch that in the language of ‘better’, rather than ‘smaller’. And that’s not misleading either – while we need less cars, we also need healthier cities that are more enjoyable to live in. Both things are true, it’s a question of which one you choose to emphasise.

4) Be unilateralist – not multilateralist

The Paris Agreement should have taught us that even if agreements are reached at a global level, unless they can be enforced at national level they are meaningless.

There’s a whole circuit of well-intentioned NGO’s, academics and journalists who are waiting for the next UN Climate Summit, thinking this will finally be the one to get climate action moving. And national leaders love the international summits because it makes them feel like super-heroes. But they are not, and the summits rarely lead to anything serious on the ground for a reason – they don’t actually exercise a lot of power. Multilateralism on climate action is a bit like multilateralism on nuclear weapons abolition – useless.

No more waiting. If international institutions push forward then great, but the action of the Green New Deal movement needs to be locally and nationally focused. Think global, act local – and national.

5) Be socialist – not capitalist

Capitalist enterprises and the markets they operate in are structurally incapable of delivering the Green New Deal. They simply are not set-up for the sort of long-term, large-scale, cross-sector action that is needed to decarbonise the economy. Just as the moon-landing and Britain’s war economy in fighting the Nazis could have only been done on the basis of massive, co-ordinated state planning, so it is for the Green New Deal.

To put it in a more practical way, think about this. In the UK we have the highest proportion of non-renewable heating in Europe; more than 90 per cent of heating is through natural gas. Heating along with transport is where most emissions are now coming from. In the space of a decade the UK needs to replace tens of millions of gas boilers with zero-carbon options. House-by-house solutions like air source heat pumps simply can not be efficiently done at that scale, speed and with adequate reliability. The only way to do this is enormously expensive, requires a mammoth co-ordination of resources and labour to the task, and means carrying out infrastructure instalments largely on a district, rather than house-by-house, basis. Capitalist markets can’t solve our heating emissions problem in a decade. Only socialism can. Full stop.

6) Be concrete – not abstract

The Green New Deal movement has to start being precise with its demands. Politicians like to get away with abstract sloganeering if they are allowed to, but we need to force them to be exacting. Take the district heating example cited above – we do not currently have the skilled workforce to carry out this scale of infrastructure change in the timescale required. So what is our government doing to train more plumbers and electricians? How is it co-ordinating them? Is it sourcing the piping material? How many houses is it going to do per year?

The challenge with concreteness is getting round the short-termism of politics, which operates to an electoral cycle and is motivated not by getting things done but by capturing headlines. The trick is to generate headlines around concrete demands.

7) Break the rules – don’t bend to the rules

The current set of rules for how economies are governed is not fit for purpose in an era of multiple ecological crisis. As a UN report by a group of Finnish academics put it, the “dominant economic theories, approaches, and models…were developed during the era of energetic and material abundance”.

In that context, it is irresponsible to limit the horizons of a Green New Deal to that which is within the constraints of national and international rules which act to thwart effective climate action. The EU’s rules on state aid, fiscal limits and ‘free’ movement of capital and goods, for instance, are a barrier to a Green New Deal. Regardless of whether states are in or outside the EU, these rules must be broken if rapid progress is to be made. Equally, Scottish political leaders should not restrict themselves only to areas of devolved competence. Climate action should be directed by need, not rules – let London and Brussels try to stop us, rather than using their rules as an excuse for our inaction.

8) Be universal – not sectional

All the great movements of history have had a universal message and have not been afraid to think big, and in so doing seizing the terrain of ‘freedom’ and ‘justice’ and making it their own. The Civil Rights movement and Martin Luther King are good examples of this. King fought for the rights of an oppressed minority, but he did so by speaking to universal values and interests, and envisioning a new world which all would benefit from.

In Nelson Mandela’s famous ‘I am prepared to die’ speech, which was in substance a 3-hour long case for the sabotage of the property of the white supremacists, he appealed to a global, universal audience, when he argued: “I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all people will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal for which I hope to live for and to see realised.”

The Green New Deal must not be pidgeon-holed as a movement only of the young, or only of the cosmopolitan. Part of the point of a movement is to overcome narrow, sectional interests and partisan political divides, and instead make a claim to speak for society as a whole.

9) Reach outside the bubble

The Green New Deal movement cannot be a Twitter phenomenon. Neither can it comfort itself with speaking to rooms full of the converted. It needs to get offline, and get out of university cities. The Green New Deal movement can have a message that speaks to people concerned about run-down town centres, about crap jobs, about a lack of decent public transport, but not if it is talking to itself.

Again, Bernie Sanders provides a decent template here. His presidential campaign has explicitly sought to reach outside the bubble. This video of Sanders getting a big cheer at a Fox News organised town hall debate is a good example of bridging divides and knocking down barriers.

The forces which have constituted the Yellow Vests, what Christophe Guilluy calls “peripheral France” – those living in rural areas and are increasingly marginalised and alienated – need to be a target constituency for the Green New Deal movement to win over.

10) Build unity – but with a purpose

Every successful movement manages to balance two competing pressures – co-option and exclusion. If a movement becomes co-opted by Establishment forces, it loses its purpose. This is an obvious concern for the Green New Deal, with governments that have no intention of making a serious Green New Deal happen already using the language to communicate its climate policies. Avoiding co-option requires having concrete demands.

But another danger is exclusion. A campaign can have the perfect Green New Deal programme, but if it doesn’t involve a large section of people who are in favour of climate action, then it’s not really a movement. A wide coalition can and should be built in favour of the Green New Deal.

So the trick is to build unity – but with a purpose. Bring as wide a group of people on board (no matter your divisions on other issues) but do so on the basis of fighting for clear demands. AOC’s Green New Deal Bill, which she is trying to get Republicans as well as Democrats on board with, is an example of the sort of unity with a purpose that can be built.

Good work Ben

Ben –

Thanks for this very helpful summary of the state of things with the Green New Deal – and for the work behind it. You’ve given me a better grasp of where we stand.

One question I’d appreciate your thoughts on, given how deeply you’ve gone into this stuff. You note that ‘there is a need to reduce global economic output’. Based on your reading, how far is there an understanding of the necessity of ‘degrowth’ within the spectrum of Green New Deals?

Invoking the original New Deal brings up connotations of a massive state-backed programme of infrastructure building – this represents a break with neoliberalism, but that’s not the same thing as recognising the need for degrowth. I guess my concern is that part of the appeal of GND is that the reference point is a mid-20th century mixed economy (WWII, the moon landings), which the left can easily get nostalgic about – and which may postpone more difficult conversations about degrowth. (After all, one of the arguments levelled at neoliberalism is that the post-70s era has seen significantly lower annual rates of GDP growth than the post-war decades.)

Coming from the left, I’m nonetheless uneasy with the idea that climate change simply validates positions that most of us would be arguing for anyway. It seems to me that the socialism that has come down to us was formed as much by the logics of an unsustainable industrial model of society (and the struggle to humanise that society) as the capitalism against which it has struggled.

Finally, when you write about the importance of telling ‘a positive story’, it seems worth pausing for a moment, given that you also acknowledge the role played by Extinction Rebellion. Because I remember exactly this argument being directed at XR in October 2018, explaining why their approach wouldn’t work – and they went on to achieve a mobilisation around climate change whose impact has exceeded anything I can think of in the UK in the last 30 years. There are plenty of valid criticisms to be made of XR, but it seems to me that their ability to mobilise activism from a place ‘beyond hope’ has a power which goes deeper than the pitch that we can ‘save the world . . . and make all of our lives better in the process’. And, as you say, the effect of this mobilisation is supportive of and not in conflict with the direction of travel represented by the GND.

I don’t mean to be polemical in voicing these questions and misgivings. I’m wrestling with this stuff myself – and keen to see what light your reading around the GND might shed on it all. When I’ve been asked about the emergence of GND over the past year, my answer has been that, even if I’m right in my misgivings, the movement of the Overton Window which these developments represent is in the direction it needs to move in, if we’re to have the conversations I would want to be having.

Hi Douglald, thanks for this thoughtful comment.

Ok, three things: De-growth, Socialism, Extinction Rebellion.

1) De-growth: I think there is a general awareness that the Green New Deal can’t be a green version of the New Deal. I think the reason why it originally got the New Deal tag was because it was an idea that started getting picked up when the 2008 crash was being compared to the 1930s, and there was a debate about what to do about it. And it’s also that think of a national mission: I think that’s where moon landing etc comes in to, it’s that sense of trying to turn climate action into a defining goal for society to mobilise around. But as I say in the article, GND economics are heterogenous, there are those that are committed de-growthers, those who are opposed to that approach and believe there is such a thing as green growth, and those that are more ambivalent about the question, and think the focus should be not on growth or de-growth but on what we value, and whether that generates growth or not is not an important (or as important) a metric. The economist Kate Raworth falls into the latter camp, see here for instance: https://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/why-degrowth-has-out-grown-its-own-name-guest-post-by-kate-raworth/ I’m inclined towards this position, though I don’t pretend to be an expert in this area. I think we have to explicitly resist attempts, like that of Ursula Von Der Leyen in the European Commission’s European Green Deal, to directly link the Green New Deal to a growth strategy for Europe, but at the same time I think it’s wrong to assume the Green New Deal to be about growth or de-growth, it’s about something much better and more concrete: a plan for rapid decarbonisation. That will include inevitably shrinking some sectors (eradicating fossil fuel extraction altogether) while at the same time growing others (e.g. we need to hire lots of people who can fit district heating systems all over the country). This is the concreteness the GND needs to bring to the climate action movement: not growth or de-growth, but a specific plan for rapid de-carbonisation. I’m not convinced that we do really need to have a philosophical discussion with the public about whether the global economy needs to shrink or not – I think it’s the wrong way to frame the problem because it doesn’t inspire and it doesn’t get to the heart of the issue.

2) Socialism: I think the traditions of socialism are very diverse. Clearly Stalinist socialism was about state-level planning to grow the industrial base each year so the USSR could compete with the US in the Cold War. But, thankfully, I don’t think that’s what most of us mean by socialism today. The reason why I would argue it’s not fundamentally tied to unsustainable logics like capitalism is that under capitalist economic development the surplus the bottom line is profitability. That mean’s there’s a structural imperative towards accumulation at the enterprise-level, which fosters a growth dynamic at the macro level, as enterprises have to accumulate more than rivals to compete. The whole notion of socialism as I understand is that the bottom line of economic development is socially defined. And eco-socialism means we can define it to meet the goal of planetary sustainability. If there is better language for explaining that simple idea I don’t know what it is.

3) I think Extinction Rebellion has been hugely important, though I see it as one part of three key elements that have emerged over the past year, the other two being Fridays for Future and the Green New Deal movement around AOC in the US. I agree with you that these things don’t have to be in conflict – there is certainly a place for direct action – but where I would place my emphasis is on building a movement that can be universal in its politics, in the sense that it should have an appeal to the whole of society. I think that’s the movement’s that ultimately win. Don’t get me wrong, you still need to be critical and attack and be negative when it’s necessary and when the opportunity is there to do so in a way that puts governments under pressure, but ultimately you need to have a universal appeal, which I’m not sure XR has.

That was a bit longer than I intended! Thanks again, it’s helped me clarify my thoughts.

Hi Ben –

Thank you for taking time to respond to my questions. There are some threads here I’d love to take further, but I’m about to go offline for the holidays so I’ll have to let it go for now.

As you might have gathered, your post sent me off into a few days of reading and reflecting around the history and implications of the Green New Deal, one result of which was this week’s essay in the Notes From Underground series I’ve been writing for Bella Caledonia:

https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2019/12/19/notes-from-underground-6-the-salvage-work/

I wrote that before I’d had your reply to the questions I posted here, and you’ll see that I’ve used some passages in your post as a way to structure my own reflections. I hope I haven’t been unfair in my reading of what you wrote – and I hope we’ll have chance to carry on the conversation, there or here, in the new year.

Meanwhile, one piece I came across in my reading stood out, and helped me to get clearer about some of the concerns I’ve been trying to articulate – so in case you haven’t come across it already, I highly recommend this from Nicholas Beuret:

https://www.viewpointmag.com/2019/10/24/green-new-deal-for-what/

Thanks again for getting me thinking.