Articles Menu

July 2020

JENNIFER NATHAN, a science educator, and I, a retired lawyer, were convicted a year ago of criminal contempt of court for acting to halt the construction of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion. Before the start of our trial, we applied at a two-day hearing on December 3-4, 2018 in the Supreme Court of British Columbia for leave to raise the common law defence of necessity, and for permission to call expert evidence at our trial about climate change and the emissions implications of continuing to expand Canada’s oil sands industry. The presiding judge, Justice Affleck, dismissed our application. Six weeks after the hearing, the judge’s written decision was released. We were convicted at a further hearing on March 11, 2019, and launched our appeal to the Court of Appeal for British Columbia the same day.

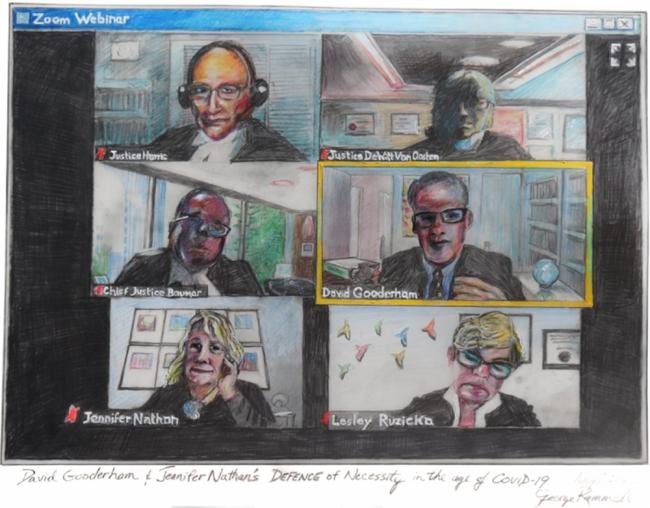

The hearing of our appeal was held on Tuesday, July 7, 2020 in the BC Court of Appeal, in Vancouver. The three-judge panel was Chief Justice Robert Bauman, Justice David Harris, and Justice Joyce DeWitt-Van Oosten. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the hearing was conducted by Zoom conference, with public access by video link.

At the one-day hearing, between 10 am and 12:30 pm, I made the oral submission by video link to the Court on behalf of Jennifer Nathan and myself. In the afternoon, Crown Counsel Leslie Ruzicka argued the case for the Prosecution.

I think George Rammell’s remarkable drawing, shown above, conveys some of the unfathomable character of the occasion of our hearing. Compared to many appeal hearings, there was very little questioning from the judges; there were no exchanges of the usual kind. Of course, from the courts’ perspective, for other good reasons, it was not an occasion for any engagement or lightness of touch. Jennifer and I were there convicted of criminal contempt of court. It was very quiet, the three judges listening—in Georges’s drawing the judge on the top left listening intently, the other two justices harder to see because of the lighting and relatively low definition of the Zoom video.

At the conclusion, the Court reserved judgment. As is usually the case after an appeal hearing, the Court will take some time to consider its decision and then issue a written judgment. We anticipate that the Court’s Reasons for Judgment will be released within approximately the next two to six weeks, although the timing is uncertain and it could be at an earlier date or later. As soon as the Court’s written decision is released, we will make it available on our website. (https://dagooderham.com/legalaction/)

There were two main issues addressed during the hearing:

One, I think the main issue, is whether the trial judge, Affleck J., made an error when he made his key finding that climate change is not an “imminent peril” in the legal sense. He found there is a “contingency” that governments and businesses may adopt what he described as ”societal measures” that will avoid any “dire outcome” (I am borrowing the language used by Affleck J. in his judgment in paragraph 55). Because he made a finding that such societal measures may be adopted in future, he concluded that a very grave outcome is not a “virtual certainty” but is just in the realm of what is “foreseeable or likely.” He took the view that unless we can prove that a dire climate outcome is “virtually certain,” the common law defence of necessity cannot succeed.

Our case is that the trial judge’s finding about the existence of such a contingency was not based on any evidence contained in the record. In short, he drew an inference—about both the intentions of governments and businesses to act and also about the economic and technological viability of unidentified future “societal measures” that he envisioned might solve the problem within the very short and unforgiving timeline remaining - an inference that we say has no foundation in any of the evidence that was presented to him at the trial.

In consequence, the appeal hearing (in terms of our approach to the hearing) required that we undertake a very detailed review of the actual evidence, the evidence contained in the record that we presented to Affleck J. We had to demonstrate, in effect, that there is nothing in the record that could have provided a reasoned basis for Affleck’s finding.

The record of evidence in this case consists of the detailed written summary of the proposed evidence that we sought to call at a full trial. It is found in the Appellants’ Outline of Proposed Evidence (a link to that 119-page document is on our website). The adjudicative record also includes affidavits sworn by Jennifer Nathan and myself.

At the hearing, our oral submission to the Court of Appeal, which took about two hours, was heavily focused on reviewing the details of the evidence in the Outline that we had originally presented to the trial judge in December 2018, including on matters of climate science (i.e., the atmospheric carbon concentration level and its current rate of increase); baseline projections of global emissions to 2030 (all of which unfortunately show global emissions are going to continue going up to 2030 and beyond); and a summary of the results of a series of other reports from the IPCC and other sources (including, in particular, the UN Emissions Gap Report 2017) all showing unequivocally that global emissions must in absolute terms go down 25 to 50 percent by 2030 (those figures represent the reductions required from all countries on average by 2030) to have any realistic chance of staying within the 1.5 degrees C or even within the 2 degrees C warming limit. We also referred to other evidence showing that, in many of the poorer countries like India, emissions are going to continue increasing at least to 2030—because those countries do not have the means to quickly reverse the trend of their rapidly increasing emissions.

We pointed to evidence in the record showing that any prospect of achieving the enormous reductions needed by 2030 would have to depend on even deeper cuts by a relatively small number of rich advanced economies, like Canada, which do have the capital and technological capacity to achieve much deeper emissions reductions in the short term, but have chosen not to do so.

On that point, our submission addressed the sorry record of Canada’s emissions, and we cited multiple reports showing how rising emissions from expanding oil sands production since 2005 are driving our national emissions far above even Canada’s existing modest reduction target. It is a very dark story.

This was probably the first time in Canada that a detailed presentation of evidence showing the gravity of the unfolding climate peril has been presented in a courtroom, and certainly the first time at the appeal court level. (The National Energy Board inquiry during the Trans Mountain Pipeline approval process simply refused to accept any evidence about climate science or emissions). The terrible subject has been largely kept out of the judicial system. Of course, the Carbon Pricing Reference cases over the past two years in the Courts of Appeal of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario did address climate change obliquely, but they were really cases about which jurisdictions (Federal or provincial) have the constitutional power to impose carbon taxes. And none of the Carbon Pricing decisions came anywhere close to touching the questions about how bad it is, or whether Canada’s efforts are remotely on track to make any contribution to avoiding a grave outcome. (On this point, our Reply Factum addresses the very limited scope of what the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal’s judgment had to say about climate change and the nature of the threat, in its Carbon Pricing Reference decision.)

For more detail on our science and emissions evidence, a useful summary of that is found in our main Factum (Appellants’ Factum) filed November 18, 2019, at paragraphs 9 to 55 (pages 2-14). Our oral submission on July 7 followed the sequence of the sections (I - VI) laid out in those 12 pages.

The second major issue on the appeal concerns the question of whether Jennifer Nathan’s conduct and my conduct in disobeying the court injunction was “involuntary conduct” within the special meaning of that term in the earlier cases. I will not expand on that issue here. However, that question is fully addressed in our Reply (Appellants’ Reply Factum), at paragraphs 6 to 16 (pages 3-6), under the heading "“Voluntary” conduct and moral choice.”

Lastly, in advance of our hearing we filed the Appellants’ Supplementary Factum that addresses two foreign law decisions. The most important is Urgenda v. The State of the Netherlands. The judgment released by the Supreme Court of the Netherlands in January 2020 is the first ruling by a senior level court in the EU or US concluding that climate change is an “imminent peril.” It affirmed an earlier ruling by the Hague Court of Appeal in 2018. The original trial in that case was in 2015. The Court of Appeal decision is only about 20 pages and is very readable. It provides a good analysis of the climate science evidence, from the perspective of the legal process. Our website has a link to an essay I prepared a few months ago about the Urgenda case, and how closely the Dutch courts were guided by the science in arriving at their decision. Links to the judgments in that case are given in List of Authorities, on the back page of our Supplementary Factum.

David Gooderham practiced in civil litigation in Vancouver for 35 years, retiring in 2012. For more information, including background and eventual outcome of the appeal, please see https://dagooderham.com/legalaction/