Articles Menu

June 7, 2021

As tenants trying to live through the pandemic, we’ve been stressed about paying the rent as our landlords wield the threat of eviction, often leaving us with no choice but to expose ourselves to COVID-19 in our workplaces.

Meanwhile, our landlords have enjoyed balanced portfolios. In their 2020 annual report, CAPREIT, one of Canada’s largest landlords, boasts “record performance despite COVID-19 pandemic.” The landlord cites average rent increases of approximately $107, or 7.9%, when units turned over from one tenant to another, which happened to 18.7% of their units, or around 11,000 units.

The key to achieving monthly rent hikes this steep is a high "tenant removal rate," as some landlords call it. Eviction, sometimes engineered through a unit’s renovation, repossession or demolition, is the primary method by which landlords increase their profit margins.

Many provinces had put in place eviction bans early on in the pandemic. But as soon as landlord-tenant boards reopened in the summer and fall of 2020, eviction notices were processed. And because rent payment is prioritized above all else, even public health orders, tenants were forced out of their homes.

So, as tenants at the mercy of the rental market, how do we fight to stay in our homes, and save our communities?

I spoke with organizers from Parkdale Organize, Vancouver Tenants Union, and Brick by Brick, to learn more about their tactics and ideas for tenant organizing in the housing crisis. Each group is in a different city, Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal respectively, and subject to their provinces' rental regulations, but their organizing tactics are universal.

Parkdale Organize (Toronto)

Parkdale Organize (PO), a volunteer-run group composed of tenants and workers in Toronto’s south-west borough of Parkdale, has turned the individual vulnerability of tenants into collective power. Like links in a chain, PO organizes tenants first in their buildings, and then forges solidarity between buildings to organize around issues that affect the entire community.

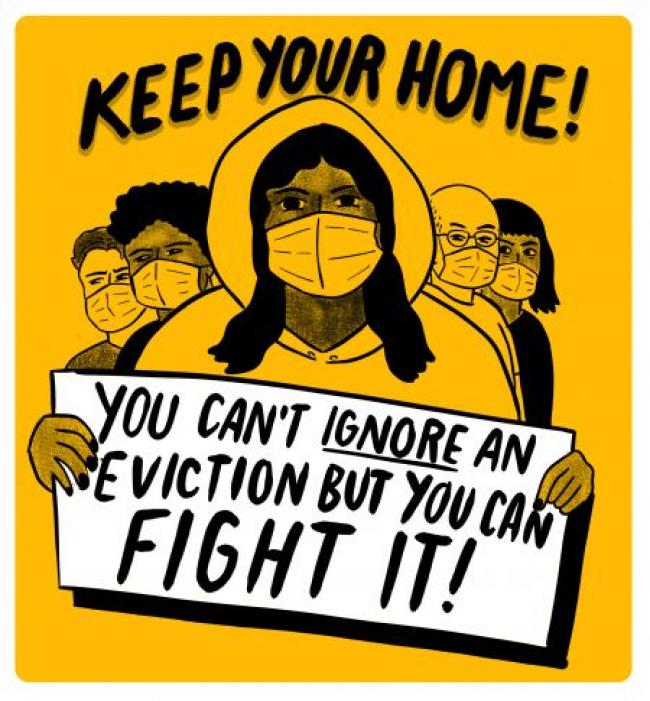

“Counterintuitively, as we know that [rent] arrears have gone up in our neighbourhood, we’ve seen applications for evictions going down,” PO member Ashleigh Doherty tells me. She estimates that throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a 50-60% decrease in evictions in Parkdale, largely thanks to the organizing that happened around the Keep Your Rent campaign started by PO in March of last year.

In March of 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, PO conducted a survey of tenants and found that roughly 10% weren’t going to be able to make rent on the first of the month. Without collective action, the Parkdale community risked losing a significant number of their neighbours. PO mobilized tenants across class lines in the Keep Your Rent campaign, where, in solidarity with their neighbours most affected by the pandemic, tenants collectively didn’t pay rent on April 1st.

And the campaign worked. Instead of facing Ontario’s Landlord and Tenant Board individually, an institution which is meant to “isolate and disempower tenants” according to Doherty, tenants dealt with their landlords altogether.

Rent withholding, rent reductions, phone zaps, visits to the offices and homes of landlords, and issuing mass complaint and repair forms with firm deadlines for landlords to abide by are some of the tactics PO has used throughout the pandemic.

“The end result of our actions in Parkdale was that the largest landlord in the neighbourhood has still not issued [...] eviction notices for rent arrears in COVID, ” Doherty shares.

Vancouver Tenants Union

“Nothing really ever happens [at city council] unless it has the support [of] [...] the landlords and developers [...] in this city,” Vancouver Tenants Union (VTU) organizer Mariah Gillis tells me.

She’s referring to a motion proposed at Vancouver’s City Council a little over a year ago, that would grant government funds to Landlord B.C., a landlord lobby group, to administer an energy retrofit program to make older buildings more energy-efficient. An amendment was added to the motion to apply rent control to retrofitted units, ensuring vacancy control and affordable rent for both new and existing tenants, a modification to the motion VTU advocated for. City Council passed the motion, but councillors walked back their vote just minutes later, nixing the entire program.

“[The] landlord lobby called city council and threatened that if they don't rescind the motion, they won't support them, and the right-wing city councillors gave in,” Gillis explains. “We focus more now on real community organizing.”

Like workers struggling against their bosses, tenants facing landlords alone have little strength. In the demoviction and renoviction capital of Canada, Vancouver Tenants Union (VTU) aims to make the individual tenant struggle a city-wide collective one.

VTU does a range of organizing, including supporting community members resisting eviction, preparing tenants facing hearings at their Residential Tenancy Branch (the provincial body that deals with all residential rental issues) and advocacy around motions pertaining to tenancy at City Council, even though VTU organizers know that these are landlord-friendly spaces.

VTU’s mere existence threatens landlords. “We have to be a little bit paranoid because we have had landlords say explicitly that they want to try and infiltrate us to get a list of our members and build like a blacklist [of tenants].”

Despite the pandemic and landlord intimidation, VTU continues to organize. They’re focusing now on helping tenants across the country create their own tenant unions, so that tenants can represent their buildings and communities, fight for renters’ rights and interests as a collective, and gain community control of our homes and neighbourhoods.

Brick By Brick in Parc-Extension (Montreal)

In 2016, the year Parc-Extension-based non-profit Brick by Brick was founded, the University of Montreal received $84 million from the federal government and $145 million in provincial funding for its new campus on the south side of the neighbourhood. Parc-Ex (as Parc-Extension is often called) is a long-time landing spot for new immigrants, and one of Canada’s poorest neighbourhoods; with no measures to lessen the impacts of gentrification, the new campus and incoming students would threaten the entire neighbourhood with eviction.

In response, community members banded together to resist displacement. Residents are helping each other fight abusive rent increases and eviction notices, organizing rallies, and lobbying the city and university for social housing.

Montreal has a long history of fighting developers and creating alternatives to commodified housing, and Brick by Brick is a promising new model for non-profit housing.

Created in response to Parc-Ex’s housing crisis and community organizing, Brick by Brick’s mission is to provide non-profit housing “for people who face discrimination in the rental market”, founder Faiz Abhuani tells me.

Brick by Brick’s funding model isn’t that of a typical non-profit. Abhuani worked in the community sector for years, and knows about the strings and limitations that come with the grant-based funding models community organizations usually operate with. For Brick by Brick to be successful, he needed to envision a different way to fund the organization.

Abhuani realized that many of the people against gentrification aren’t poor, but actually quite well-off. “These people want to challenge big developers, but their money is sitting in banks in RRSPs, and is actually funding those big developers'', according to Abhuani.

So Abhuani manufactured a different kind of non-profit funding model: Brick by Brick would issue community bonds to people looking for real estate investments, which would fund non-profit social housing for tenants marginalized by the rental market. For investors, backing a Brick by Brick project allows them to make interest off real estate, without extorting tenants like Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) shareholders do.

Brick by Brick was set to buy an old paint factory in Parc-Ex as their first project, when the housing market soared, and they were priced out. Luckily, it was the City of Montreal who outbid them, and later agreed to sell the property to the organization at a discount.

Brick by Brick plans to transform the factory into a 30-unit non-profit apartment complex, mostly for families, with about a dozen studios and one bedroom units. The pandemic has slowed the renovation process, but Abhuani estimates it will be ready to house its first tenants in about 3 years.

What should be done

While Parkdale Organize, Vancouver Tenants Union, and Brick by Brick all use different tactics, they organize for the same reason: developers are eating away at our neighbourhoods, and politicians side with developers, not tenants, at nearly every stage.

For years, tenants have been calling for stricter controls on rent increases and evictions. And again, throughout the pandemic, we’ve made our needs exceedingly clear: enact a moratorium on evictions, and forgive rent debt.

But our political representatives have responded with lukewarm, temporary measures—while many of them profit off of the housing crisis. Since the beginning of the pandemic, at least 8 MPs, seven Liberal and one Conservative, disclosed new rental property assets. And in 2020, about a quarter of elected officials sitting in Parliament and over 18% of those in the Ontario Legislature reported supplementing their salaries with rental income.

As political economist Ricardo Tranjan tells me, “It’s not complicated, it’s not rocket science [...]. We don’t need more research on this, we don’t need some super sophisticated elaborated policy, we don’t need another 300 page housing strategy. No. We know the solution, we’re just not seeing the political will to implement it.”

Uninhibited by significant regulations, landlords will continue to treat tenants like cash cows to extract the highest possible profit. With our homes at the whim of the market, collective organizing is the only tool we have to stave off eviction, while we build alternatives to commodified housing.

[Top image: Illustration from the Toronto-based Keep Your Rent campaign.]