Articles Menu

Jan. 4, 2022

Growing awareness of contemporary injustices towards First Nations children and a landmark court ruling this fall forced the federal government to reach agreements seeking to settle cases of discrimination in the child welfare system, says the First Nations advocate who led the fight for change.

Cindy Blackstock, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, called the agreements words on paper, but said in an interview that she will measure progress at the level of First Nations children.

The federal government has agreed to pay $20-billion in compensation to First Nations children and $20-billion for long-term reform of the First Nations child welfare system under agreements-in-principle designed to settle a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) case and separate class-action lawsuits.

Details of the agreements, which are non-binding until finalized, were released on Tuesday.

Ottawa reaches a deal on First Nations child-welfare compensation, sources say

Taking back control of child welfare services is a turning point for the Inuvialuit

“Although this is very encouraging in terms of a plan, what is really important to me is when this plan actually gets implemented and makes a difference in lives of children, to end this ongoing discrimination,” Dr. Blackstock said.

The agreements include compensation for First Nations children on-reserve and in Yukon removed from their homes between April 1, 1991, and March 31, 2022, and for their families. They also pledge long-term reform of the child welfare system to ensure that discrimination found by the tribunal is never repeated, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) said.

The tribunal also found that changes the federal government has made in recent years have not been sufficient.

Dr. Blackstock said the agreements are the result of Indigenous people bringing past injustices to light, and the resulting increase in awareness among Canadians.

“I think it is a credit to the young people in care, and the residential school survivors, and the 60s scoop, and the murdered and missing Indigenous women and the Canadian public who have become more aware of the contemporary injustices to First Nations kids,” she said. “That along with the landmark loss of the federal government in court has created a scenario where the government had to act.”

Dr. Blackstock said public pressure needs to continue until change occurs.

“What we know from governments in the past is that symbols like a non-binding agreement, symbols like signing ceremonies, etc. are intended to kind of send a message to the public that the problem has been dealt with,” she said. “Too often, the problem doesn’t get dealt with. And what we need to watch is whether or not they actually deliver on these agreements.”

Negotiations facilitated by former Truth and Reconciliation Commission chair Murray Sinclair wrapped up late on New Year’s Eve with parties to the tribunal case ― the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations ― and the lawsuits.

In a statement, Mr. Sinclair thanked the parties for their work over the past few months on behalf of First Nations children and called the agreements-in-principle an “important milestone.” He also said he looked forward to collaboration over the coming months to secure a positive final agreement.

The federal government said on Tuesday that the agreements will provide a basis for final settlements to be negotiated in the coming months.

In 2019, the CHRT found Ottawa wilfully and recklessly discriminated against Indigenous children on reserve by failing to provide funding for child and family services. It also ordered the government to provide up to $40,000 to each First Nations child who was unnecessarily taken into care on or after Jan. 1, 2006. It added that its orders also cover parents or grandparents and children denied essential services.

In September, Ottawa’s request for a judicial review of the CHRT findings was rejected, a decision released on the eve of the first federal National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

In December, the federal government said it would earmark $40-billion to compensate First Nations children and families for the failures of Canada’s child-welfare system and to pay for long-term reform, in the hopes of settling the matter before the end of the year. Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller said the settlement would be the largest in Canadian history.

Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu on Tuesday pointed out that when she was appointed to her portfolio in October she said litigation was not serving anyone. She said she hopes the country has learned that discrimination is not only extremely painful to those experiencing it, but extremely costly to the government.

Mr. Miller noted that no amount of money can reverse the harm to First Nations children.

“When it comes to reconciliation, I think we all have to realize once and for all, you can want reconciliation all you want, but it ain’t free,” he said. “There’s a cost to it, but it’s an important one.”

In October, the government announced it would appeal the September Federal Court decision that upheld the CHRT finding. Ottawa said at the time it agreed to put a pause on the litigation while it negotiated with First Nations groups.

Justice Minister David Lametti said the federal government intends to drop the appeal when a final agreement is reached.

Assembly of First Nations Manitoba Regional Chief Cindy Woodhouse, who was involved in the negotiations, said the settlement will affect more than 200,000 children and their families. No amount of money will bring back a lost childhood, she said, but added she hopes the agreements will bring about change.

Lawyer David Sterns, who is involved in class actions covered by the settlement, said Indigenous groups tried many times to persuade the government to make changes before they filed legal challenges.

“It took the strong arm of the law to bring government into the unavoidable realization that it was a flawed, racist and discriminatory system,” he said. “They fought this thing all the way through.”

The parties agreed that after a deal is finalized – there is a deadline of March 31 – the settlement will go to the CHRT and the Federal Court for approval, Mr. Sterns said.

The compensation agreement will likely be different than what the tribunal approved, and he said “we would want the tribunal’s blessing that the departure is fair and reasonable.” The Federal Court would be asked to decide whether the settlement is in the best interests of those who suffered harm from government child-welfare policy.

The NDP’s Charlie Angus and Lori Idlout said the settlement is necessary because “for years, there was a massive amount of damage deliberately inflicted on First Nations children.”

Conservative Indigenous Services critic Jamie Schmale said serious negotiations should have been completed years ago, and the continuation of legal action had a devastating impact on Indigenous children and communities.

Chief Bobby Cameron of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations said “discriminatory funding and other racist decisions have led to a massive overrepresentation of First Nations children in the system, all at the hand of a federal child welfare system that should’ve protected them.”

“The healing journey begins by keeping First Nations children and young people within our own families and communities,” he said.

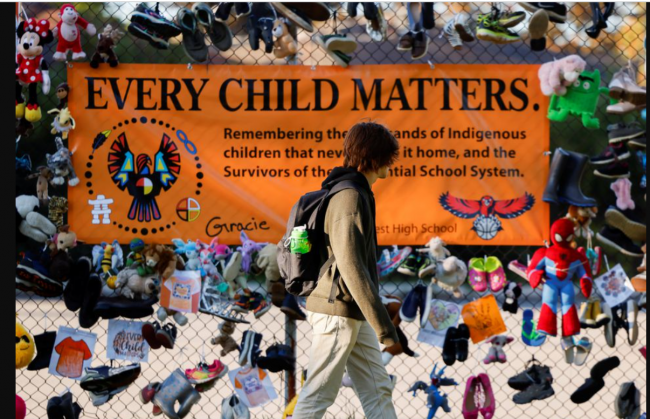

[Top photo: A student walks past a display at Hillcrest High School on Canada's first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, honouring the lost children and survivors of Indigenous residential schools, their families and communities, in Ottawa on Sept. 30, 2021.BLAIR GABLE/REUTERS]