Articles Menu

Mar. 28, 2022

Last Tuesday, we awoke to news the federal Liberals and NDP had entered into a “supply-and-confidence agreement” (SACA). The agreement would see them collaborate on a shared policy agenda, and so long as the terms of the SACA are honoured, the NDP will pass the Liberals’ next four budgets and support other confidence motions, allowing the Liberals to maintain government until June 2025.

Let me state at the outset of this analysis that I am a longtime fan of minority governments, of fixed election dates and of confidence-and-supply agreements that allow minority Parliaments to govern with some stability and give collaborative expression to the wishes of a broader base of voters. I was particularly keen about the BC NDP-Green Party confidence-and-supply agreement and sang its praises when it was signed in my home province in 2017.

A few days after last September’s federal election, I wrote a column recommending a similar Liberal-NDP agreement. “We need to make this minority Parliament do its job and meet this moment with us,” I said then. “As this new government takes shape, rather than lurching from one confidence motion to the next, as we witnessed over the last two years, how about we stabilize our political lives with a formal Confidence and Supply Agreement.”

Sadly, however, I am much less enthused about the contents of the deal just cemented. As I wrote after the election, “the NDP needs to send a clear message to the Trudeau government — no climate emergency plan, no deal.” Instead, what the NDP managed to secure in this agreement feels weak and vague, especially with respect to the climate crisis.

The NDP has touted its two big policy wins in the deal — an income-tested dental plan and a pharmacare plan. These would be significant additions to health-care coverage in Canada. But only the dental plan has concrete, time-specific language, while the pharmacare rollout remains ambiguous. In my post-election column, I urged the NDP to make both a dental plan and pharmacare part of a SACA deal, but thought these two programs should be part of a much longer list of bold climate and inequality policy measures.

I appreciate that, in practice, negotiations like this are challenging. But the concessions the NDP extracted from the Liberals seem very modest. Other than the dental care commitment and a couple other minor pledges, the rest of the SACA policy agenda is lifted pretty much right out of the Liberals’ election platform. It is true that, in the past, the Liberals have often failed to implement their election promises. So, arguably, the SACA will force them to keep their word this time. But it feels odd to have the NDP’s great success here be “we helped the Liberals keep their promises,” as opposed to “we forced them to up their ambition on the key challenges of our time.”

What makes the negotiation of a SACA so tricky is that once the deal is done, the junior partner forgoes most of their political leverage. With the threat of denying parliamentary confidence withdrawn, the NDP has lost its ability to force further concessions — so long as the letter of the agreement is respected and the Liberals move forward with the policy agenda spelled out in the SACA (and in the absence of some egregious scandal), the NDP is now obliged to honour its side of the deal. That’s why so much hinges on ensuring the content and specificity of the SACA is robust and worth the forfeiting of future demands. Given this, the content of this deal feels decidedly light.

This is especially so with respect to the climate crisis. The five climate planks of the deal — in their entirety — read …

Opinion: We face a climate emergency — that is the existential threat of our time that must be decisively tackled in the three-year life of this agreement. And this agreement does not spell out an emergency plan, writes columnist @SethDKlein. #SACA - Twitter Tackling the climate crisis and creating good-paying jobs:

Tackling the climate crisis and creating good-paying jobs:

To be clear, these promises are all lifted from the Liberal platform. The only new commitment, if you can call it that, is “to identify ways to further accelerate the trajectory to achieve net-zero emissions no later than 2050,” whatever that will mean.

The NDP failed to extract additional climate commitments in the SACA, even though its 2021 election platform contained some worthy climate proposals, and goodness knows there is much needed to up the ambition of the Liberals’ current approach. Sadly, with this deal, the NDP has effectively reinforced the Liberals’ election claim they had nothing additional to contribute on this defining task of our lives.

I’ve written previously about why tackling inequality and the climate crisis must go hand-in-hand. If and when we finally ask people to engage in a grand societal undertaking — as the climate emergency demands — this invitation must come with a promise that the society that emerges from the other side of this transformation will be more just and fair than the one we are leaving behind. This is a key lesson of all societal mobilizations. That’s how we get everyone on the bus.

If we fail to link a bold climate program to ambitious action on the crisis of inequality, then too many people will see climate policies as elitist (a perception to which the Trudeau Liberals are already too vulnerable).

And yet the only specific policy measure in the SACA that speaks to enhancing tax fairness in the face of growing inequality is a pledge to “move forward in the near term on tax changes on financial institutions who have made strong profits during the pandemic.”

Again, this is simply a restatement of the Liberals’ election platform promise to bring in a surtax on big banks and financial institutions. We surely need that. But where is the NDP’s excellent proposal to bring in a wealth tax? Where’s its recent proposal to also impose a windfall surtax on oil and gas companies that are currently making a killing and on all the other companies that have so obscenely profiteered during the pandemic? Again, these worthy ideas were forfeited in the SACA negotiations.

And that’s not just disappointing, it’s dangerous. Because without concrete measures like these, we give fodder to a right-wing populist backlash that capitalizes on perceptions the economy is “rigged” in favour of these wealthy corporate elites.

For an agreement that assures passage of four federal budgets, it is notable that the SACA contains no specific spending commitments with respect to the climate crisis. There is no major monetary pledge for just transition, even though a Just Transition Act without money will be largely meaningless. Yet, a key marker of genuine climate emergency action is that we spend what it takes to win.

I’ve long said, in keeping with the recommendations of former World Bank chief economist Nicholas Stern, that Canada should be spending two per cent of GDP on climate mitigation measures (equivalent to about $40 billion a year, or about five times what we are currently spending on climate). There is no commitment like that in the SACA. But now, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO has been pressuring its member countries to boost their military spending, coincidentally, to two per cent of GDP. The Trudeau government may well be inclined to oblige. The NDP would traditionally oppose such a move, and rightly so. But by agreeing to support the next four federal budgets, might the NDP have committed itself to such a gross ramp-up of military spending?

All spending decisions have opportunity costs, and it would be tragic in the extreme if we end up deploying our resources on more military hardware instead of against the real security threat of our time — the climate emergency.

Those of us who reside in British Columbia know a thing or two about confidence-and-supply agreements, having recently lived under one for three years. It’s worth noting that the text of the B.C. agreement was both more ambitious and detailed than the new federal SACA. It was by comparison a far more exciting and transformative document.

That said, the BC Green Party — the junior partner in this case — came to learn a few hard lessons about such deals. First, the language and details in an agreement have to be very specific, as the dominant party will fully avail itself of any wiggle room the pact allows. Second, the government will do as it pleases on matters left silent in the agreement, and the junior party can do little to stop them (witness the BC Greens’ inability to block the expansion of fracking and LNG, which were left unnamed in the agreement).

And third, the dominant party will break the deal if and when it feels it can win a majority government. Claiming the pandemic required a new and stable mandate, but in truth sensing that a majority was in reach, the Horgan government broke its agreement with the BC Greens a year and a half early. Ironically, in the year and a half since, and with that majority secured, the BC NDP government has accomplished less — and with less accountability — than it did under the confidence-and-supply agreement.

Here’s what’s got me most nervous.

In 2025, when this agreement is scheduled to end, the Liberals will have been in government for 10 years. In the natural political flow of things, a 2025 election will be a “change election,” and we could see a return of a Conservative government. Indeed, this prospect is what makes the absence of meaningful electoral reform such a troubling omission from the SACA; a mutual Liberal-NDP commitment to bring in proportional representation would greatly enhance our chances of ensuring — over the long term — that the will of Canada’s broad progressive majority continues to be reflected in the composition of Parliament.

Forward progress on the climate file is never guaranteed. Change is a fact of life in politics. That said, some policies, programs and institutions can be embedded in a manner that makes them harder to undo. Once a popular new institution or social program (like medicare and child care) is in place, it is very hard for even a right-wing government to dislodge it.

The centrepiece of the Liberals’ climate plan, however, remains the escalating carbon price. Yet Pierre Poilievre has made clear that, if he were prime minister, he’d scrap carbon pricing pronto. The Liberals are also putting great stock in other incentive-based programs like tax credits and rebates, which again can be readily abandoned, as governments like those of Ford in Ontario have shown.

We urgently need bold climate policies and programs in place — a new federal Just Transition Transfer, a Youth Climate Corps, new climate Crown corporations, and massive fixed climate infrastructure investments in transit and renewable energy — that cannot be easily undone or reversed. The SACA has little to offer in this regard.

And take note: this week, when Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault tables the Emissions Reduction Plan — the federal government’s updated climate plan to meet its 2030 greenhouse gas emissions reduction target — pay attention to how many of the commitments are back-end loaded to the latter half of this decade. Politically, those promises may be of little consequence.

Instead, judge the plan by how many bold near-term commitments it includes — ambitious policy measures and new climate institutions that are “Poilievre-resistant.”

And if Justin Trudeau and Jagmeet Singh wish to build upon the spirit of co-operation they say is captured in the SACA — and place a ratchet behind what progress they plan to make in the next three years — then they will act quickly to secure an additional agreement on proportional representation.

This SACA has its strengths and pluses.

The promised new dental care and pharmacare programs the NDP secured are important — they will make a significant difference to thousands of families.

Implementing strong climate policy and other important social and economic policies takes time, and securing three years of political stability to allow for such implementation is a good thing.

Modelling more cross-party collaboration and co-operation in government is worthy, as well. I think, in re-electing a minority Parliament last fall, Canadians asked for that.

But we face a climate emergency — that is the existential threat of our time that must be decisively tackled in the three-year life of this agreement. And this agreement does not spell out an emergency plan.

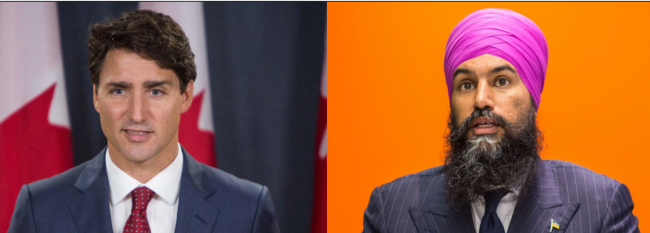

[Top image: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (left) and NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh. Photos by Alex Tétreault]