Articles Menu

Sept. 8, 2022

The Coastal GasLink pipeline is currently B.C.’s most infamous — with the arrests of Indigenous land defenders and journalists, repeated environmental infractions and celebrity activism from the likes of Mark Ruffalo, Greta Thunberg and Leonardo DiCaprio.

But the list of controversial pipeline projects in the province doesn’t stop there.

There’s Pacific Trails, which would parallel the Coastal GasLink route across Wet’suwet’en territory and Prince Rupert Gas Transmission, a pipeline intended to cut through the Kispiox Valley — a proposal that brought members of the Gitxsan Nation and locals from all walks of life together in opposition. And, of course, there’s the federally owned Trans Mountain pipeline, which continues to be met with fierce opposition from First Nations and allies along the route as construction impacts ecosystems, most recently disrupting salmon runs on the Coquihalla River.

And, waiting in the wings for its chance to ship fracked gas from northeast B.C. to overseas markets, is a project quietly clinging to the dream of a liquified natural gas (LNG) boom that was promised more than a decade ago. It’s called Westcoast Connector Gas Transmission.

If you’ve never heard of it, you’re not alone.

That year, Shell scrapped a planned liquefaction and export facility near Prince Rupert that would have received gas from the pipeline and, despite opposition from some stakeholders, Enbridge applied for and received a five-year extension to the project’s approval in 2019. When that extension was granted, the company was told it must have “substantially started” the project by Nov. 25, 2024. To date, that hasn’t happened. With the deadline nearing, stakeholders along the pipeline route received notice of the company’s intent to file for a rare second extension.

According to B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, only two projects have ever received a second certificate extension — Seabridge’s KSM mine on the Alaska border and Taseko’s New Prosperity mine on Tsilhqot’in First Nation territory.

If the extension isn’t granted, they’d need to start the lengthy environmental assessment process all over again.

“There is a ton of new information since 2014 — new information on climate, new information on Indigenous Rights and new protected areas,” Naxginkw Tara Marsden, who works on land use planning and governance issues with the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs, told The Narwhal in an interview. “As a whole I can’t see all of that being ignored in an extension request, but we’ll see.”

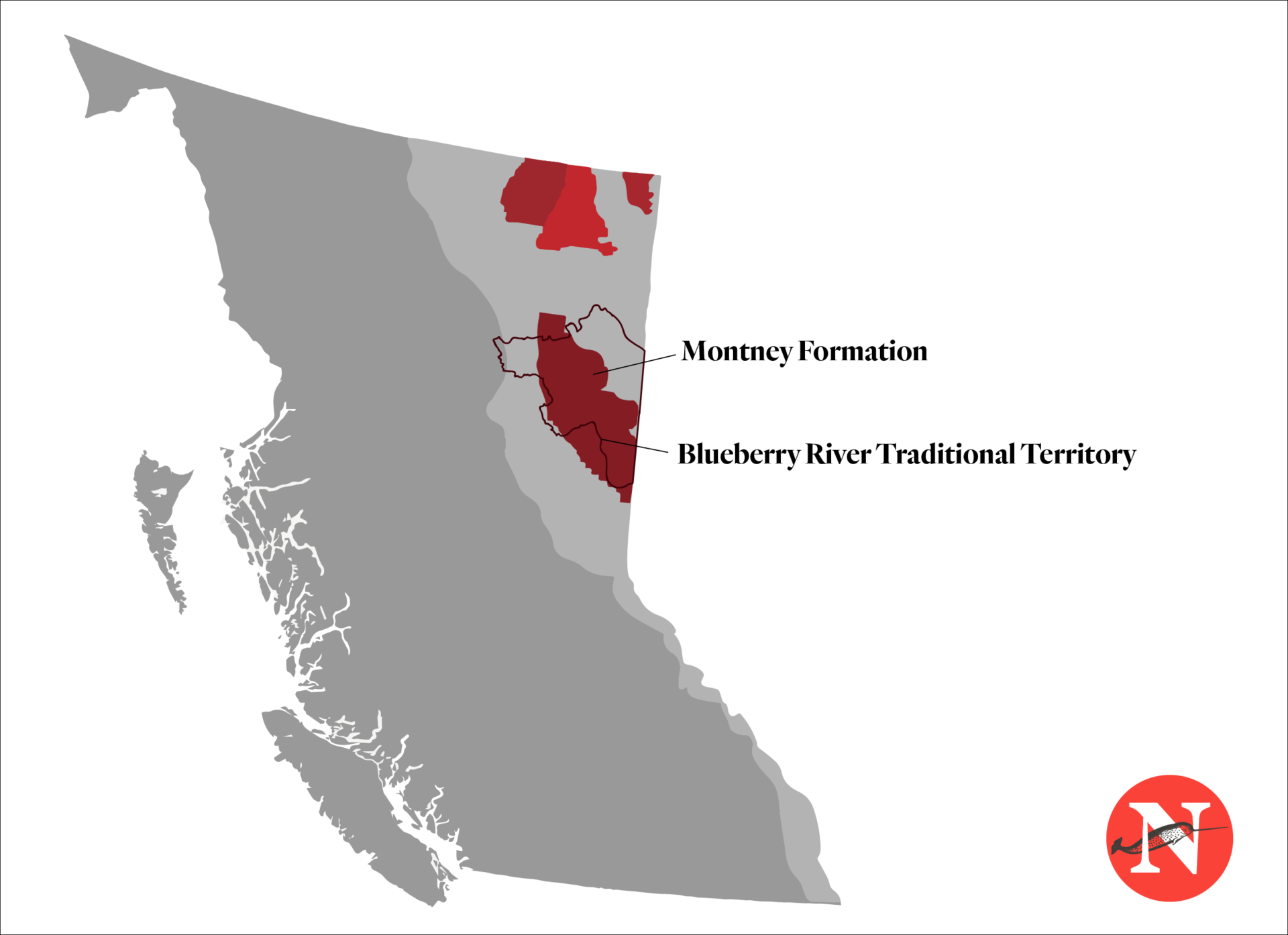

In addition to the extension, the company recently asked the B.C. government for permission to shorten the pipeline by removing a section of its proposed route in the northeast, 100 kilometres of which overlaps a First Nations’ territory at the heart of a 2021 B.C. Supreme Court ruling on Treaty Rights.

The landmark ruling, often referred to as the Yahey decision after former chief Marvin Yahey, found the province guilty of infringing on Blueberry River First Nations’ rights by permitting and encouraging widespread industrial development.

Here’s what we know about the project and its proposed changes.

The 850-kilometre pipeline — roughly 700 kilometres if B.C. approves the amendment request — would tap into existing infrastructure in the northeast and transport fracked gas to the west coast for liquefaction and export.

The project, as approved, is described as “a pipeline system consisting of either one or two adjacent pipelines” and would be capable of moving 8.4 billion cubic feet of fracked gas daily. That’s four times the amount Coastal GasLink plans to transport during its first phase of operations.

The Westcoast Connector pipeline would not traverse Wet’suwet’en territory — where Hereditary Chiefs oppose the Coastal GasLink project. Its route would cross the province further north, including transecting Gitxsan and Gitanyow territories and crossing the Skeena and Kispiox rivers — both important salmon and steelhead rivers.

Enbridge noted in its recent letter to the environmental assessment office it is “actively developing the project” to build the first Westcoast pipeline and “continues to work on development opportunities for the second pipeline in the future.”

But the company told The Narwhal in an email the “project is in the early stages of development” and final decisions haven’t been made on whether it will proceed, or when.

“The Westcoast Connector Gas Transmission project is not yet approved — we still require additional permits,” a spokesperson wrote.

The environmental assessment approval is the major hurdle for projects but, when construction is imminent, the pipeline will require permits issued by the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission. Permitting is a regulatory process and applications can be submitted for multiple activities at one time. Those applications draw on technical studies conducted during assessment.

The project was originally slated to deliver gas to one of several proposed liquefaction and export facilities near Prince Rupert, none of which are still on the table. Now, the project is listed as a potential supplier for the proposed Ksi Lisims LNG plant on Nisg̱a’a territory. Ksi Lisims is a partnership between the Nisg̱a’a Nation, a consortium of Canadian gas producers called Rockies LNG and Texas-based Western LNG.

Enbridge hadn’t filed an extension request with the province prior to publication, but it is signaling that this will be the next step.

In July, Enbridge made a presentation to Terrace city council citing the main reasons for extending its certificate as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Blueberry River First Nations court decision. The company told the council it spent $10 million on the project in 2022 and noted it is actively engaging potential LNG terminal developers and gas producing partners.

“At this point we’re still engaging with Indigenous nations to better understand their perspective and we have not confirmed any commercial partners,” Enbridge told The Narwhal in an emailed statement. “If this project proceeds, we will be completing an environmental protection plan that will specify the measures required to protect wildlife.”

The company said it is considering applying for the extension but does not know when that might happen.

Gavin Smith, a lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law, told The Narwhal he’s concerned an extension could pave the way forward for a flood of related requests.

“We have seen both with Taseko’s New Prosperity and with KSM in recent years willingness from the provincial government to effectively bend the rules about how long [environmental assessment] certificates are supposed to remain valid,” he said. “Those rules exist for a good reason, which is that … certificates are granted on a lot of complex information, input from communities and so on, that can become stale-dated if left for too long.”

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy told The Narwhal every request is carefully reviewed and the context of the request considered.

“For any extension request, the environmental assessment office and statutory decision-maker consider it on its own merits and its specific circumstances through a robust and transparent process,” the ministry wrote in an emailed statement.

Marsden said an additional concern is how the province handles feedback from communities.

“When they came to us with the KSM extension, they said, ‘What’s changed? Is there new information you’d like to share?’ ” she explained. “We shared new information — there’s climate change, there’s new recognition of Indigenous Rights and requirements for consent. And [the province] came back and said, ‘Well, that’s not how we define new information.’ ”

“There’s no definition of what new information is, it’s this really circular argument of whatever you say doesn’t really matter but we are going to go through this process of seeing if you have anything new to say.”

The ministry argued the KSM decision did reflect input from First Nations and other stakeholders, noting the extension included extra conditions that provide the province with “an additional level of regulatory oversight to require that management plans remain current and reflect the best available science and management practices.”

Smith said by extending approvals past legislated guidelines, B.C. could be setting the stage for future conflicts.

“Look at the changing legal realities around implementation and recognition of the [United Nations] Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that were not at the forefront 15 to 20 years ago,” he said. “Those types of changes are relevant to how environmental assessments are carried out.”

In a word: no.

While the extension request would buy Enbridge breathing room until 2029, it’s not the only way to keep the proposed pipeline alive. If a project is deemed to be “substantially started” — a determination made by B.C.’s environmental assessment office partly on sunk costs and on the scale of work completed — it effectively locks in the approval indefinitely.

For example, the Pacific Trails pipeline, that Enbridge bought from Chevron and Woodside Petroleum in early 2022, received “substantially started” designation in 2016. This means its certificate — which was granted in 2008 based on studies conducted in the years prior — remains valid regardless of any changes on the land.

“It’s good for forever, essentially,” Marsden said. “It’s a big investment of money, but then they’re safe in terms of not having to ever re-apply.”

She said the KSM extension and the imminent request from Enbridge show how companies “want to keep riding the market — they want to keep waiting for that sweet spot where they’re going to get the prices and they’re going to be able to build this thing.”

With governments worldwide pledging major emissions reductions as part of climate commitments, the fossil fuel industry continues to pivot to different business models. The push to export gas from B.C. reserves was initially pegged as a means to “transition” from other fuels such as coal.

But prevailing science now agrees that methane — the main component of natural gas — poses even more of a threat to the climate than conventional fossil fuels. In an April press release, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that methane emissions need to be reduced by more than 30 per cent by 2030 to limit warming to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels.

“Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible,” Jim Skea, with the panel, said.

But open market prices for natural gas remain high, in part because of the energy crunch caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Companies like Enbridge still see potential profits from developing projects like Westcoast Connector.

“Given how completely crazy the global LNG markets have been this year, I can imagine that Enbridge may see some real upside to keeping the project alive,” Clark Williams-Derry, energy finance analyst with the Ohio-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, told The Narwhal.

“In my view, Enbridge is making an economic calculation: there’s a benefit to keeping the project alive, there’s a cost to keeping it alive and there’s a cost to letting it die,” he explained. “They’re weighing the costs and benefits — and seem to be deciding that the benefits are worth the costs.”

He said keeping the project on the table is low-risk, financially.

“If you declare the project dead, development costs have to be written off and recognized as a loss,” he said. “Plus there also can be ‘soft’ costs for letting a project die — costs to executives’ reputations, to investors’ views about a company’s future prospects, etc.”

“Meanwhile, it often doesn’t take a whole lot of money or effort to keep a project alive,” he added. “A bit of paperwork, a bit of staff time now and again.”

Marsden said the province needs to ask some tough questions about where B.C. is heading in terms of its economy in light of climate change.

“Do you want to risk a bunch of other things that are at play to ensure this industry is prioritized? Or do you want to take a pause and reconsider things?”

The request to remove a section of the pipeline route seems like an example of a fossil fuel company adapting to minimize conflict on Indigenous Rights issues.

In a letter to B.C.’s environmental assessment office in May, Enbridge wrote that “removing the first 138 kilometres of the pipeline from the project as certified will reduce potential cumulative effects on Treaty 8 territory, including those within Blueberry River First Nations territory.”

However, a spokesperson for the company told The Narwhal in an email that “the removal of a 138 km [section] of the pipeline route … is not related to the Yahey decision.” Enbridge did not respond to follow up questions apart from noting the company determined the section “would no longer be required.”

Just how far-reaching the impacts of the Yahey decision will be is still unknown but in the short-term, B.C. has put the brakes on any new development on Blueberry River First Nations territory. In October, the province and nations reached an interim agreement that allows projects approved before the court ruling to proceed, but pauses any new authorizations or permits as the nation negotiates a final agreement with the province.

That means if those “additional permits” Enbridge said it needs to move forward are for work on the territory, the project could be tied up for an unknown amount of time.

Blueberry River First Nations opposed the Westcoast Connector from the outset.

During the project’s environmental assessment, the nations’ lands and resource department flagged numerous concerns, submitting a comprehensive report on cumulative impacts. In one of multiple letters filed to the province, the community expressed frustration around the consultation process, saying the few opportunities given to provide feedback were “no more than opportunities to blow off steam.”

That October 2014 letter continues: “Aside from the [environmental assessment] process, there has been no engagement by the provincial Crown in consultation with [Blueberry River First Nations] on the project or on the larger LNG development proposed in B.C., including on the very significant development that will be induced in our territory as a result of the construction and operation of LNG facilities on B.C.’s coast, serviced by pipelines from [our] territory.”

Earlier, in a June 2014 letter, the nation wrote that it was “deeply troubled by the conclusion that there are no identified potential effects of the project on … habitation, hunting, fishing, trapping or gathering practices.”

Despite Enbridge’s statement that its desire to shorten the pipeline is not related to the Yahey decision, that June letter was echoed in its amendment request. By removing the section, the company wrote, the project would reduce or eliminate potential impacts on critical caribou habitat, 50 wetlands, 135 water crossings and “hunting, trapping, fishing and plant gathering locations, trails and travelways, habitation sites and gathering and sacred sites.”

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy confirmed it is reviewing the request and told The Narwhal it will “provide an opportunity for federal, provincial, and local governments, and First Nations and Indigenous people to provide advice and inform the … review.”

The ministry said responding to a request like this typically takes three to six months.

In the era when Westcoast Connector was first proposed, it was just one of many LNG projects brought to municipalities and First Nations across northern B.C. The province cast its net wide to gain support, signing agreements with numerous band councils and other forms of First Nations governments under John Rustad, the former minister of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation. (Rustad was recently removed from the Liberal caucus for publicly promoting climate change denial.)

Enbridge told The Narwhal it was “pre-emptive” to ask questions about its relationships with First Nations and did not supply any information about agreements it may have with communities along the pipeline route. However, a provincial government webpage shows that six Indigenous governments have signed benefits agreements in support of Westcoast Connector or associated infrastructure — though many of them signed before Enbridge was in charge.

“Spectra was a very well established company in B.C.,” Marsden said. “They had many natural gas pipelines that were sort of familiar to people and had really dedicated a lot of time and resources to building quite strong relationships.”

But, she said, Enbridge is a different company.

“Many of the nations, including Gitanyow, opposed the oil pipeline that Enbridge proposed with Northern Gateway. With the reputation of Enbridge and what their interests have been in trying to get oil to the west coast, that’s a huge concern for me, personally, and for others as well at Gitanyow. Is this an attempt to try and get another oil pipeline through? We don’t have that certainty and until we do, it’s still a potential threat.”

The pipeline also faces potential opposition from the Gitxsan Nation.

In early August, a Gitxsan house group, Wilps Gwininitxw, declared 170,000 hectares of territory an Indigenous Protected Area, where it will prioritize maintaining an intact watershed that’s home to mountain goats, wolverines and grizzlies. The area is just upstream of the Westcoast pipeline route and TC Energy’s Prince Rupert Gas Transmission line. In a statement released following the announcement of the protected area, the house group noted both pipelines would “directly affect Wilps Gwininitxw by crossing our salmon-bearing rivers and streams.”

“In the absence of meaningful provincial or federal government action to protect the Skeena watershed from industrial development, Wilps Gwininitxw is unilaterally declaring their territories protected.”

It is unclear how the Indigenous Protected Area will impact the pipeline project should it proceed to permitting and construction.

[Top image: Enbridge's little-known northern B.C. pipeline would transport up to 8.4 billion cubic feet of fracked gas daily. The company is seeking an amendment that would shorten its route and avoid Blueberry River First Nations territory, and considering a request for an extension that would keep the project in play until 2029.

Illustration: Shawn Parkinson / The Narwhal]