Articles Menu

The global operational capacity of carbon capture and storage (CCS) currently stands at 39 megatonnes (Mt) of CO2 per year, or roughly 0.1% of global annual emissions, with deployment slow and plagued by accidents. And despite its fervid marketing as a climate saviour, CCS today is primarily used merely to extract more fossil fuels.

The UK alone “would need to quadruple the entire global CCS capacity by 2050 to achieve its net-zero targets,” writes Renew Economy, citing new research conducted by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Research on behalf of Friends of the Earth Scotland and Global Witness. “According to the Global CCS Institute, less than a fifth of CCS capacity under development in 2010 was operational by 2019.”

A recently-discovered problem at Australia’s only operating CCS project, which stores collected carbon under the seabed, was yet another signal that the technology remains to be perfected. “The plant’s owners, Chevron, found that a large volume of sand is blocking the flow of water from the facility,” writes Renew Economy.

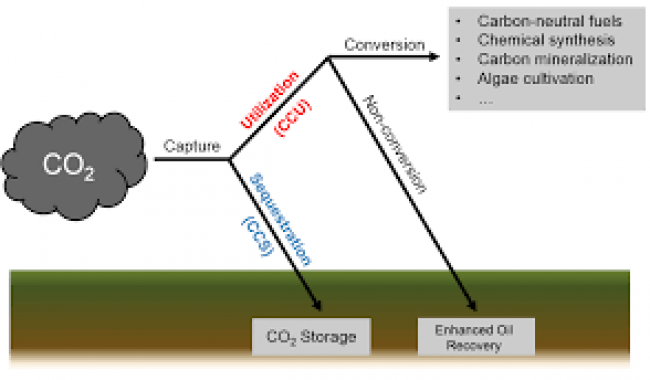

And even the CCS capacity that exists does little to reduce atmospheric carbon concentrations—instead, it’s deployed in the extraction of fossil fuels, the Tyndall report notes. Many CCS systems employ so-called enhanced oil recovery (EOR), a process in which captured carbon is used to push otherwise inaccessible oil deposits closer to the surface, to be extracted and burned.

That technique is the end use of 81% of carbon captured through these systems, reports CBC News.

“People have heard about carbon capture, they have this sort of warm and fuzzy idea that… this can be something good to save us,” said policy expert June Sekera, who reviewed 200 research papers on CCS. “And that’s because they have this impression that we can have carbon-neutral fossil fuels.”

Not so, confirmed CO2 removal expert and Harvard PhD candidate Andrew Bergman. “Talking about the ‘carbon content’ of oil extracted using enhanced oil recovery obscures the fact that [it’s] a process, very simply, for extracting oil,” he told CBC. “Oil itself cannot be net-negative. Oil is oil.”

That makes CCS little more than a dangerous lifeline to fossil extractors at a time when the world needs to vigorously accelerate uptake of renewables, said Dale Marshall, national climate program manager with Environmental Defence.

Yet—wonder of wonders—Big Fossil is lobbying hard for investment in the technology. Reuters reports that Royal Dutch Shell and Exxon Mobil are among the oil majors petitioning for US$2.5 billion in subsidies for a project aiming to store CO2 emitted by Rotterdam port factories into empty gas fields in the North Sea.

That funding would be exactly half the $5 billion in subsidies the Dutch government has vowed to grant in 2021 “for technologies that will help it achieve its climate goals.”

Meanwhile, modelling by an international group of climate policy analysts shows how (dangerously) attractive direct air capture of carbon (DACC) technologies could become in a world where climate policy is increasingly dictated by crisis thinking. “The logic of crisis politics suggests that the climate crisis may open new spigots of public spending, but do little to weaken entrenched interest groups that have often impeded costly policy action,” writes a team of researchers from the Deep Decarbonization Initiative, in a new study recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

In an ironic twist, they add, “big emitting industrial practices could remain in place even as societies becomes increasingly agitated about climate change and willing to spend massively on solutions.”