Articles Menu

Feb. 19, 2024

“To a water expert, looking ahead is like the view from a locomotive, 10 seconds before the train wreck.” — The late scientist David Schindler on Alberta’s looming crisis

Alberta’s water reckoning has begun in earnest. Snowpack accumulations in the Oldman River basin, the Bow River basin and the North Saskatchewan River basin range from 33 to 62 per cent below normal. A reduced snowpack means less summer water for the fish and all water drinkers.

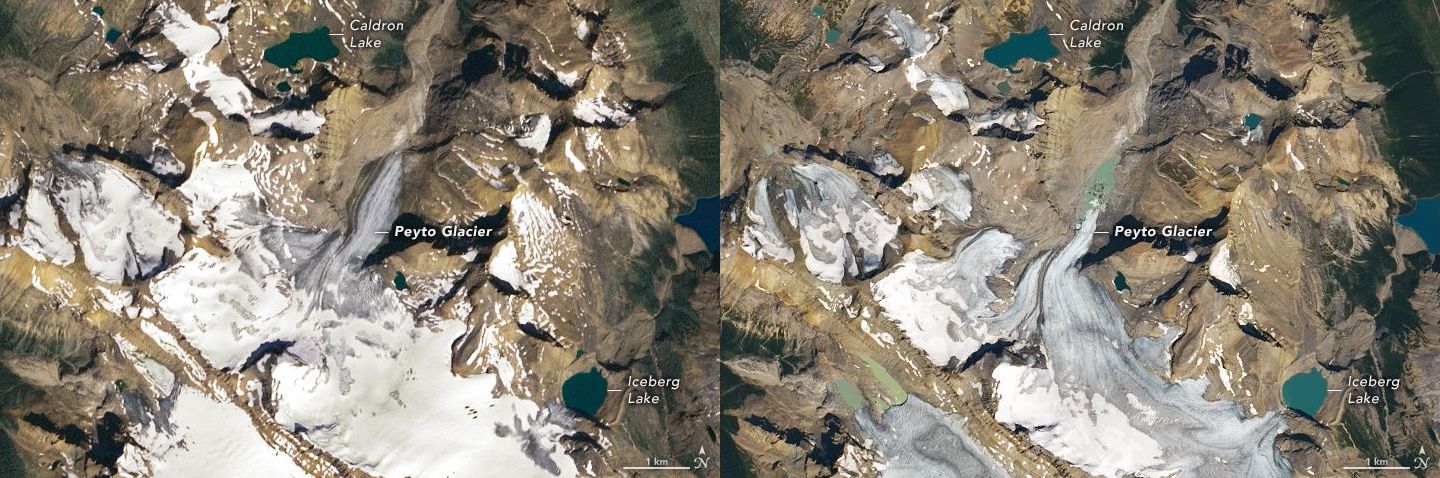

Ancient glaciers that feed and top up prairie rivers in the late summer melted at record speeds last year, the hottest on global records. Many indomitable ice packs, such as the well-studied Peyto Glacier, are disappearing altogether, wasted by the desiccating hand of climate disorder.

Fifty-one river basins from Milk River to Hay River report critical water shortages due to low rainfall and high temperatures, according to the provincial government.

Groundwater levels in parts of Alberta have reached record lows. Wells in Rocky View County just outside of Calgary, for example, show steady declines and the lowest levels ever measured. Some 600,000 rural Albertans depend on groundwater.

Most of the province’s water reservoirs sit five metres below their normal waterlines, boat launch docks projecting over baked earth like monuments from a lost civilization.

The Oldman River Dam, a $500-million megaproject built for the irrigation industry, has become a desert of silt cut by a narrow canal of chocolate water. It sits at 30 per cent capacity. Normally it ranges from 60 to 80 per cent full.

St. Mary Reservoir normally was between 40 and 70 per cent full. Today, at 11 per cent capacity, it has become a ghost of a water body. The Spray Lakes Reservoir, high in Kananaskis country, reports 34 per cent of capacity.

Lake Diefenbaker, from which the people of Saskatchewan get 60 per cent of their drinking water, received only 28 per cent of normal inflow last year from heat-stricken Alberta, a plummet scientists called “unprecedented.”

With less water in the rivers and ground, the cottonwoods and willows that decorate the banks of prairie rivers are dying.

Parched rural communities have even begun to question the huge thirst of the powerful oil and gas industry. A water commission that provides potable water to the municipalities of Innisfail, Bowden, Olds, Didsbury, Carstairs and Crossfield has banned treated bulk water supplies to the fracking industry, which permanently removes water from the water cycle. One study recently noted that water consumption by frackers “intensifies local water competition and alters water supply threatened by climate variability.”

Yet the Alberta government has not declared an emergency. It says it is planning for extreme drought but hoping for snow and rain.

Meanwhile Danielle Smith’s United Conservative Party government has appointed an advisory body with no known water experts. But it does include Ian Anderson, a promoter of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion that will transport bitumen from the oilsands to the Port of Vancouver, criss-crossing many dwindling rivers, creeks and streams as it does.

Predicted by tree rings and scientists

Alberta’s water emergency, which is also a fire emergency, was foretold by scores of water scientists. They predicted that prolonged water scarcity would hit southern Alberta hard for stubborn geographical reasons.

No one sounded the alarm more persistently and urgently than the late David Schindler, one of the world’s great water ecologists.

Schindler never tired of reminding Albertans that their province has only 2.2 per cent of Canada’s renewable fresh water. Meanwhile its industries, government and residents behaved as though water came from ever-flowing taps instead of dwindling glaciers, rivers, aquifers and snowpacks.

There’s another ignored reality. Eighty per cent of Alberta’s water flows north while 80 per cent of the province’s growing population lives in the drier portion south of Edmonton.

“Sometime in the coming century, the increasing demand for water, the increasing scarcity of water due to climate warming, and one of the long droughts of past centuries will collide, and Albertans will learn first-hand what water scarcity is all about,” warned Schindler nearly two decades ago.

Schindler explicitly forecasted that collision when he and fellow researcher Bill Donahue wrote a paper on the impending water crisis facing the Canadian prairies for the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal. It appeared in 2006 with much fanfare.

The big water problem, said Schindler and Donahue, really began in the early part of the 20th century, when European settlers occupied the prairies during a period of unusually stable and moist conditions in the Canadian West. Federal reports also misled immigrants by informing them that cacti were no sign of aridity. The settlers wrongly assumed that the good water conditions would persist.

But extended wet periods aren’t normal on the prairies. In earlier centuries, long droughts made the land thirsty for decades at a time, and then the drought would recede like some hellish glacier. Tree ring data from 1,000-year-old limber pine shows some of the worst dry spells occurred in the 1500s and 1720s. But recent instrument records upon which modern water allocations are based provide a too-small window that leaves the region’s long, dry history out of consideration.

Even the Dirty ’30s and the recent drought that damaged crops in the 2000s were mild affairs compared with these historic events, wrote Schindler and Donahue. No one in modern Alberta has really planned for prolonged dry spells, let alone the ability of climate change to magnify their impacts. Indigenous people, of course, adapted to the drought challenge by being nomadic; they kept their footprint small.

Schindler and Donahue then noted that government policies started to drain the rivers, wetlands and aquifers for malls, casinos, gas wells and farms without thinking how these waters depended on healthy snowpacks and glaciers in the Rocky Mountains.

Next Schindler and Donahue looked at trends in air temperature, rainfall and river flows in a world disrupted by the warming emissions of fossil fuels. They selected 10 sites on the prairies with 80 years of weather records. Most showed warming of one to four degrees. Half showed rainfall declines by 14 to 24 per cent. None showed increased rainfall.

Then they looked at summer water flows because that’s when irrigation, municipal water withdrawals and seasonal evaporation are at their highest. Summer flow for the majority of prairie rivers declined rapidly in the 20th century.

But that hasn’t caused a rethink about Alberta’s approach to agriculture. The province today is the site of about 60 per cent of Canada’s irrigation.

The flow of the Athabasca River, upon which oilsands production depends, declined by 30 per cent between 1970 and 2003.

When Schindler and Donahue issued their report, on dammed rivers such as the Peace and the Oldman, summer flows had fallen 40 to 60 per cent below historic measures. The South Saskatchewan had suffered badly; its flow had fallen by 84 per cent since the 1900s.

Demise of the mighty glaciers

The scientists, in their paper, turned their attention to trends in glacier mass and snowpack depth, which also told a story of persistent decline. The number of days that winter snow lingered on the ground had shortened. The mean depth of snowpacks had shrivelled in the last 100 years.

These dwindling snowpacks once provided water insurance for rivers in the months of May and June, noted Schindler and Donahue. But no more.

All these drying trends have been compounded by the arrival of more and more residents. The oilsands boom triggered a 15 to 20 per cent population surge between 1996 and 2001, which “rendered Alberta the most vulnerable of the western prairie provinces to water shortages,” wrote Schindler and Donahue.

At the time of their paper, Alberta boasted 3.4 million human water drinkers. Now the number tops 4.7 million, and Premier Smith has said she would like to see that population more than double.

Schindler and Donahue then cited some of the impacts of too many people and industries sopping up limited water supplies. They included six million cattle (now down to four million due to drought) and an irrigation system that gulped the majority of the water in southern basins.

They noted that water for deep-well bitumen injection in northern Alberta “currently comprises 25 per cent of licensed groundwater withdrawals, approximately equal to water licensed for municipal use.”

They also noted that freshwater withdrawal for bitumen production had also compromised the winter flow of the Athabasca River.

They added that agricultural interests combined with municipal and highway expansions had destroyed 70 per cent of the prairie’s wetlands with dire consequences. Wetlands clean water, regulate its flow and provide reliable drought insurance.

If these trends continue, warned Schindler and Donahue 18 years ago, “the combination of climate warming, increases in human populations and industry, and historic drought is likely to cause an unprecedented water crisis in the western prairie provinces.”

Evidently, if wholly unsurprisingly, Alberta has arrived at that destination.

Recommendations ignored

What could have been done? What might still be done even at this late moment?

Schindler and Donahue made a few pointed recommendations. They included:

Finally, Schindler and Donahue recommended the opposite of Premier Smith’s boosterism about attracting millions more people to live in Alberta. “It may prove wise to keep human populations in the dry WPP [western prairie provinces] relatively low, to avoid the water scarcity that has already become a major problem in the southwestern United States and many other populous dryland areas of the world.”

Only two things have changed in Alberta since the paper was published. Climate change has intensified. And those in charge are even more heedless in the demands they are willing to place on the region’s ever more scarce water.

Both Alberta and Saskatchewan, for example, have grand plans to expand irrigation during a drought.

The oilsands’ demands keep growing as well. In 2020, just four companies in the oilsands took 200 billion litres of fresh water from the Athabasca River to lubricate eight water-intensive bitumen projects. That’s more than what the city of Calgary withdraws from the Bow and Elbow rivers to slake its needs for a year.

The Tyee asked Bill Donahue about the famous paper and all it warned and prescribed. The independent water scientist and Alberta Environment’s former chief monitoring officer was blunt.

“We’re now 18 years after our PNAS paper made waves and Alberta’s in a worse position,” said the scientist, who now lives in British Columbia. “The irrigated acreage has expanded substantially, water-intensive oil and gas production has skyrocketed, mainly in the form of natural gas fracking and mined and in situ bitumen extraction, and climate change has continued to advance.

“Today’s Alberta government is completely incapable of managing something like climate change, drought and widespread water shortage because they only see environmental problems as political and ideological problems, as opposed to actual problems with potentially catastrophic real-world consequences.”

Equally stark was his assessment of leadership in Alberta Environment and the Alberta Energy Regulator and other arms of government key to dealing with the water crisis in the province. They “lack the attention span and skills to properly respond to it.”

“Dave and I tried to warn Albertans about what was coming, and unfortunately we were largely ignored,” said Donahue.

“In every presentation I’ve ever given on climate change and its effects on water supply in Alberta, I’ve always talked about the possibility that a 20- or 30- or 40-year drought could start this year, based on what the norm was for every century in the last two millennia, other than the exceptionally stable and wet 20th century.”

Brad Stelfox, an Alberta-born, highly respected land-use ecologist, says Albertans need to think about the crisis in terms of supply and demand. If there’s no demand for water, then having very little of it constitutes not a drought but simply low flow.

“Unfortunately Alberta has made lots of water allocation decisions on the poor assumption that abundant rainfall and melt water will persist forever.” When Alberta became a province in 1905, it had 160,000 people who each consumed about 50 litres of water per day, related Stelfox. Now more than 4.7 million Albertans each use eight times that amount on average.

Robert Sandford, a water expert and resident of Canmore, says Alberta won’t be alone in facing a water reckoning. He told The Tyee: “Fire and water are different sides of the same coin but, as we have been witnessing, too much of either can create catastrophe.”

No government was ready for the Canadian wildfires of 2023, and none are prepared for the drought Alberta now faces.

“We need to hope less and do more,” exhorted Sandford, who holds the Global Water Futures Chair in Water and Climate Security at the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health.

“We now exist in a climate regime that humanity has never experienced before.” Responding with “anything less than a well-organized, aggressive and nationally coherent response could ultimately be fatal to thousands.”

“If we want to end this perfect storm — and this climate emergency — we have to wake up and act as though our lives and our futures depend upon immediate action. Because they do.”

[Top photo: St. Mary Reservoir, near Lethbridge, just 11 per cent full. Climate change is only part of the reason Alberta is reeling for lack of water. Photo via Alberta government.]