Articles Menu

Mar 30, 2021

The B.C. government is not taking advantage of a crucial opportunity to protect the coast from a potential oil spill, according to critics of the province’s recent report regarding a pending environmental certificate for the $12.6 billion Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project.

As B.C.’s environment and energy ministers consider issuing a certificate for Trans Mountain related to marine shipping, the province has an opportunity to require more detailed information on oil spill response capacities along the coast from the company.

It’s an opportunity onlookers say the province is not acting on.

But rather than require a rigorous response plan for a worst-case-scenario spill, Radzik and others say the province appears to be accepting a plan that it previously argued is inadequate and not aligned with international best practices.

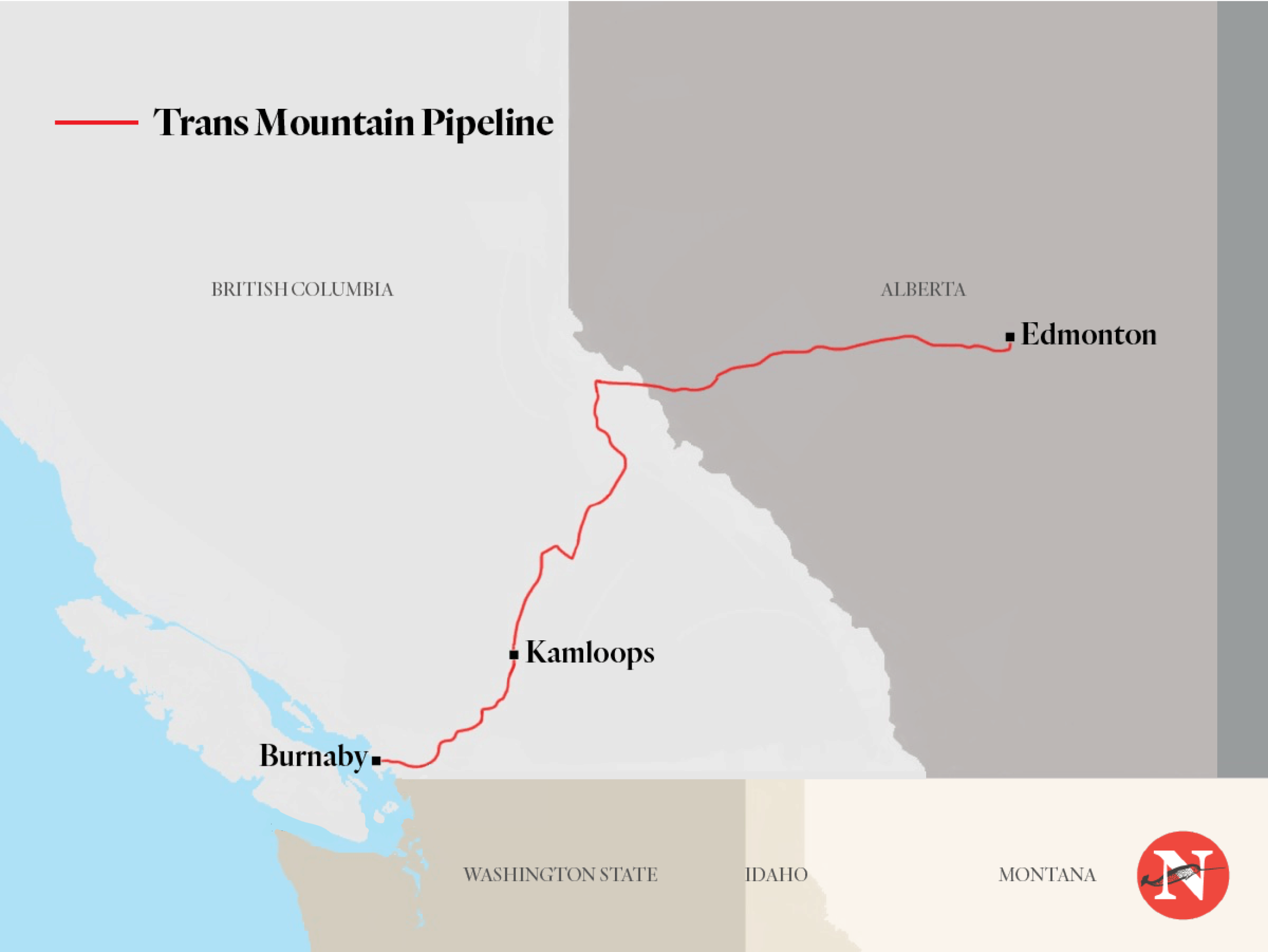

Since their 2017 election campaign, the B.C. NDP have vowed to use “every tool in the toolbox” to stop the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, which would involve twinning the 1,150-kilometre pipeline that runs from near Edmonton, Alta., to export terminals in Burnaby, B.C. The expansion project is anticipated to nearly triple the flow of diluted bitumen as well as other petroleum products in the pipeline, leading to a sevenfold increase in tanker traffic in the Burrard Inlet beside downtown Vancouver and out to shipping routes along the coast.

At the heart of the NDP government’s resistance to the pipeline project is the threat the movement of diluted bitumen presents to coastal ecosystems and, in particular, B.C.’s treasured shorelines over which the province has jurisdiction. The federal government, which purchased the pipeline in 2018, has authority over energy infrastructure that crosses provincial borders.

Yet while B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office considers granting new permits to the Trans Mountain project, Radzik points out the province is now ignoring the very same shoreline protection issues it flagged during the National Energy Board’s additional round of hearings for the pipeline in 2019.

Because of B.C.’s own assurances to use every tool to protect the coast, “we have an expectation that the province will try to defend B.C.’s interest,” Radzik said.

The route of the Trans Mountain pipeline. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The National Energy Board’s review of the pipeline expansion project has been the subject of political and legal controversy for nearly six years.

After the project was greenlit by federal cabinet in 2016, the Federal Court of Appeal overturned that decision, criticizing the National Energy Board for omitting marine shipping from the project’s initial review.

The board was ordered to produce a reconsideration report that would take a closer look at some of the issues not adequately addressed in the project’s original environmental assessment. That report, which included details of an enhanced spill response plan from Trans Mountain, was delivered in early 2019 and notes that the potential socioeconomic and environmental impacts of an oil spill could be dire and the potential impacts to endangered southern resident killer whale populations could be “potentially catastrophic.”

Read more: Trans Mountain vs. killer whales: the tradeoff Canadians need to be talking about

The reconsideration report provided the province with a fresh opportunity to respond to the potential risk of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project.

But in its draft analysis of the reconsideration report, released mid-January, which details the province’s response to the National Energy Board’s assessment of Trans Mountains marine shipping impacts, the B.C. environmental assessment office proposes only one new condition for the project, which would require Trans Mountain to produce an expert report outlining the potential human health impacts of a marine spill. It also proposes an amendment to expand the list of groups being consulted on bitumen research to include potentially impacted coastal governments.

Environmental groups and First Nations who offered feedback on B.C.’s analysis report are frustrated with the province’s limited engagement with the key issues of oil spill response capacity and shoreline protection.

“The reason the shorelines are the big concern here is because that fits into the very narrow area that the province can regulate in terms of this project,” Radzik said.

Radzik points out that B.C.’s analysis lacks transparency about existing measures and plans.

In a written response submitted as part of a public feedback process, Georgia Strait Alliance argues there still are currently “no good answers” in B.C.’s analysis to key questions about a worst-case-scenario oil spill.

According to the organization’s 25-page letter, lingering questions include who would actually clean up the oil when it hits B.C. shorelines, how many people would be needed to clean it up and where those people would come from.

“There is no specific standard for cleanup. There is no publicly available analysis of what differences there might be in shoreline cleanup between diluted or weathered bitumen and standard shoreline cleanup techniques,” their response states.

“There is no modelling presented for how cleanup will proceed or what the rate and intensity of cleanup will be. We do not know what types and amounts of equipment are required. There is nothing to indicate how testing and verification of plan assumptions will occur.”

Pipe stored near Hope, B.C., for anticipated work on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project. Photo: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

In its written response to the province’s analysis, the Tsleil-Waututh Nation outlined similar concerns and asked the province to hold true to what it had said during the National Energy Board hearings in 2019.

During those hearings, the B.C. government pointed out examples of specific shortfalls in Trans Mountain’s spill response plan, including inadequacies in Transport Canada’s standards as well as in the federal government’s $1.5 billion Oceans Protection Plan, which includes $12 million for enhanced protection of killer whales and an additional $9 million to reduce collisions between ships and whales.

But despite the significant focus placed on the Oceans Protection Plan in the National Energy Board’s initial review of the project, B.C. criticized the lack of specifics, saying the province only found “vague, high-level information on an assortment of initiatives.” In particular, B.C. noted that the board pointed to the use of chemical spill treating agents as a potential response to an oil spill on the B.C. coast, despite the fact that Canada does not allow the use of these chemicals, which can have additional ecological impacts.

B.C. also previously raised questions about Trans Mountain’s reliance on Western Canada Marine Response Corporation, a private contractor, to respond to an oil spill. Despite Trans Mountain’s enhanced oil spill response plan, which notes Western Canada Marine Response Corporation’s increased capacity to address an oil spill, B.C. argues Trans Mountain’s standards and plans fall short of oil spill preparedness offered by responders in the Salish Sea just across the Canada-U.S. border.

Despite these previously raised concerns, B.C.’s latest analysis report does not demand improvements to or greater details regarding these elements of Trans Mountain’s spill response regime.

“Tsleil-Waututh reminds the province that in your own words to the NEB … you outlined in detail how these jurisdictions and programs did not address risk,” the nation’s letter states.

“Shoreline protection from the risk of spill and from erosion from marine shipping has not been adequately addressed.”

Tsleil-Waututh’s statement goes on to say how the province continues to shift responsibility to other jurisdictions rather than doing what is within its own powers to protect B.C.’s coast.

“Without revisions, this report will leave the coast of British Columbia vulnerable to the risks of a spill from this project,” the letter continues. “The province must ensure provincial resources are sufficiently protected and hold Trans Mountain and the federal government agencies to account.”

A statement sent to The Narwhal from B.C.’s Ministry of Environment said it received 619 responses to the province’s analysis of the reconsideration report during the public comment period which ended March 1. These responses, the statement said, are currently being analyzed and will inform potential updates to the analysis.

The province will continue to urge the federal government to ensure “the strongest protections possible” are put in place to protect the environment and public safety, according to the ministry’s statement.

“Our government remains concerned about the risks posed by diluted bitumen and the potential of a catastrophic oil spill on our coast,” it said.

“Those responsible for spills should also be responsible for fixing the environmental damage they’ve caused.”

Participants gathering in canoes during a Tsleil-Waututh Nation water ceremony in 2017. The Westridge refinery can be seen in the background. Photo: Zack Embree / Tsleil-Waututh Nation Sacred Trust

The Environmental Assessment Office is expected to release another draft version of the province’s analysis report in April to summarize feedback received during the public comment period, and will then continue with further engagement with First Nations and other affected parties, according to the province.

The ministry said it expects to finalize its reconsideration report this summer and provide it to ministers, who will look at adding or amending conditions in Trans Mountain’s environmental assessment certificate.

Eugene Kung, a staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law whose work has focused on Trans Mountain, said if the point of the Environmental Assessment Office’s report is to provide information for ministers to make an informed decision about whether or not to approve the environmental assessment certificate, there needs to be more analysis.

“That to me includes an informed analysis of the existing [spill response] regime and conditions,” he said. “Shouldn’t it include an analysis of the effectiveness of those measures?”

The province should work to maximize and overlap environmental protections as much as possible, Kung said, but “unfortunately that’s not what we’re seeing.”

Kung noted the province is faced with a key opportunity to enhance the protection of the coast and act on the critiques that the province itself identified during the National Energy Board hearings.

“I think ultimately the question is how confident do they feel in the existing measures and if and when there is a spill, will they feel like they did everything they could to be prepared?” he said.

Radzik said if B.C. doesn’t take the opportunity to add protections, it will look like it’s not just passing the buck, but is “closer to surrender.”

“This is squarely something the province could do something about, but now it’s not acting,” he said.

“This is them saying, ‘We’re going to leave certain tools in the toolbox,’ ” Radzik said. “ ‘And we’re going to leave them because the feds have tools, we don’t know if they work, but we know that they’re there.’ ”

[Top photo: A aerial view of Kinder Morgan's Trans Mountain marine terminal, in Burnaby, B.C. Photo: Jonathan Hayward / The Canadian Press]