On the heels of the last significant police action on Wet’suwet’en territory, B.C. quietly embarked on a process to “streamline” its response to what it saw as a rising wave of protests across the province.

Weeks after the RCMP arrested 30 people on Nov. 18 and 19, 2021, along the Coastal GasLink pipeline route, the Civil Disobedience Work Plan was launched by B.C.’s Public Safety Ministry following direction from the premier’s office, according to documents obtained by The Tyee through freedom of information requests.

In addition to CGL opposition, the province was concerned with protests against old-growth logging at Fairy Creek and demonstrations that began in February 2022 against vaccine mandates and other COVID-19 measures.

“Government, law enforcement and the justice system recognize that all Canadians have the right to peaceful protest,” the Public Safety Ministry’s Policing and Security Branch wrote in internal briefing notes introducing the initiative in early 2022. “However, the magnitude and frequency of protests that have exceeded the boundaries of this right and interfere with public safety, private enterprise, government operations and civil society have demonstrated that the current tools to deal with this issue are insufficiently robust.”

Efforts to develop a plan got underway on Jan. 25, 2022, with a meeting among the Ministry of the Attorney General, the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General and police leaders, according to the documents.

The work plan was meant to result in a “new model” for managing civil disobedience in B.C., according to an internal briefing note prepared for deputy solicitor general Doug Scott on March 8, 2022.

Scott approved the work plan the following month.

It’s not clear where the process led or what changes may have resulted. The Tyee emailed questions about the Civil Disobedience Work Plan and its outcomes to B.C.’s Public Safety Ministry on Aug. 7 but the ministry did not provide a response prior to publication.

Aislin Jackson, policy staff counsel with the BC Civil Liberties Association, said one glaring omission from the work plan is public consultation.

“From the materials, it seems like they don’t see the public, who engages in protest activity, or civil society groups like ours that are watchdogs for protest rights, as stakeholders in this conversation,” Jackson told The Tyee. “When they’re talking about stakeholders, it seems like mostly they’re talking about various branches of the government and the police.”

Among the changes considered by the plan was an “Integrated Protest Response Team” to respond to civil unrest.

The plan also considered new information systems to “enhance government monitoring of protests” and ensure consistent messaging across provincial ministries, as well as plans to “update the information management system and policies to allow broader access to policing data.”

Documents show that the government also contemplated a communications strategy to combat negative publicity related to police actions, which have attracted scrutiny by First Nations groups, independent police watchdogs, human rights organizations and the courts.

“How to counteract the negative narrative re: police response. Should we do an info campaign to the public? Narratives to avoid/include?” reads a note in one document meant to track progress on the work plan.

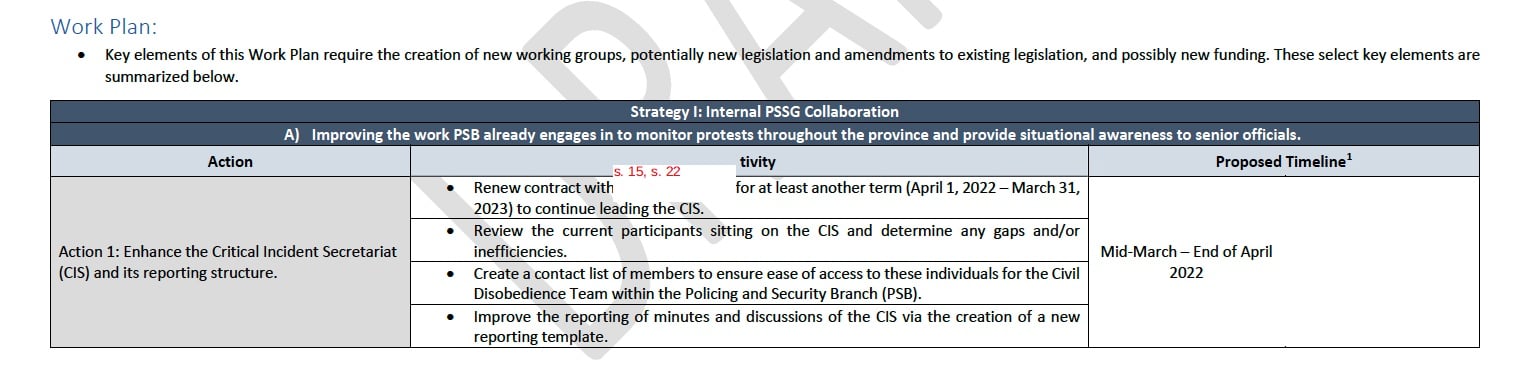

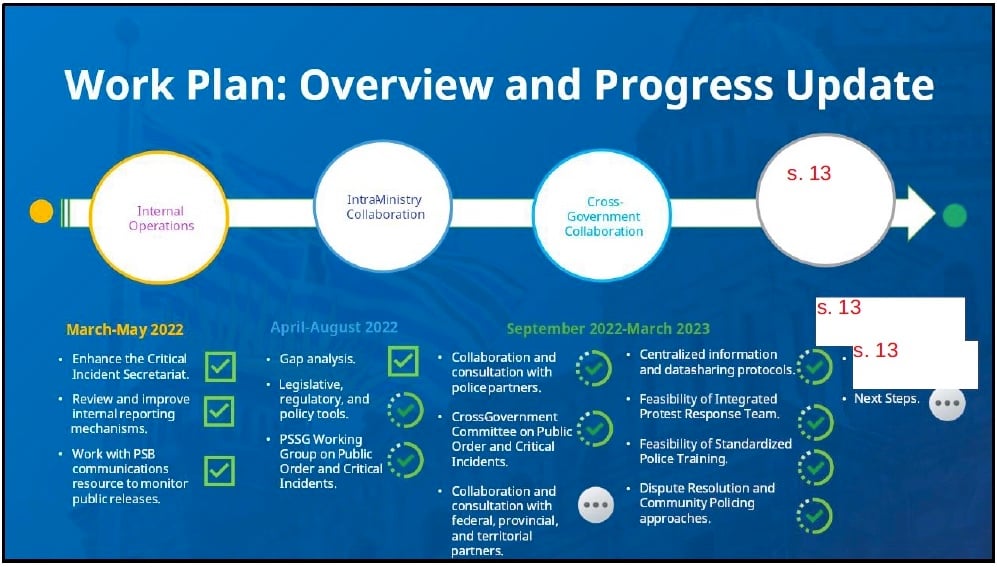

The first phase of the the Civil Disobedience Work Plan, which began in March 2022, was meant to identify gaps related to managing protests and explore “legislative, regulatory and policy tools” to improve the province’s response to civil disobedience.

The second phase, which began September 2022, would see the Public Safety Ministry play a co-ordinating role with other provincial ministries, “including those who manage projects that attract civil disobedience.”

The ministries flagged for engagement included Indigenous Relations, Lands, Forests, Energy and Mines, Environment, and Transportation, according to briefing notes. Also included were B.C.’s LNG Canada Implementation Secretariat, the BC Energy Regulator and the Environmental Assessment Office.

Little progress on Indigenous engagement, docs show

While the documents reference the need to engage Indigenous groups in a manner consistent with the province’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, it’s not clear how much, if any, engagement took place.

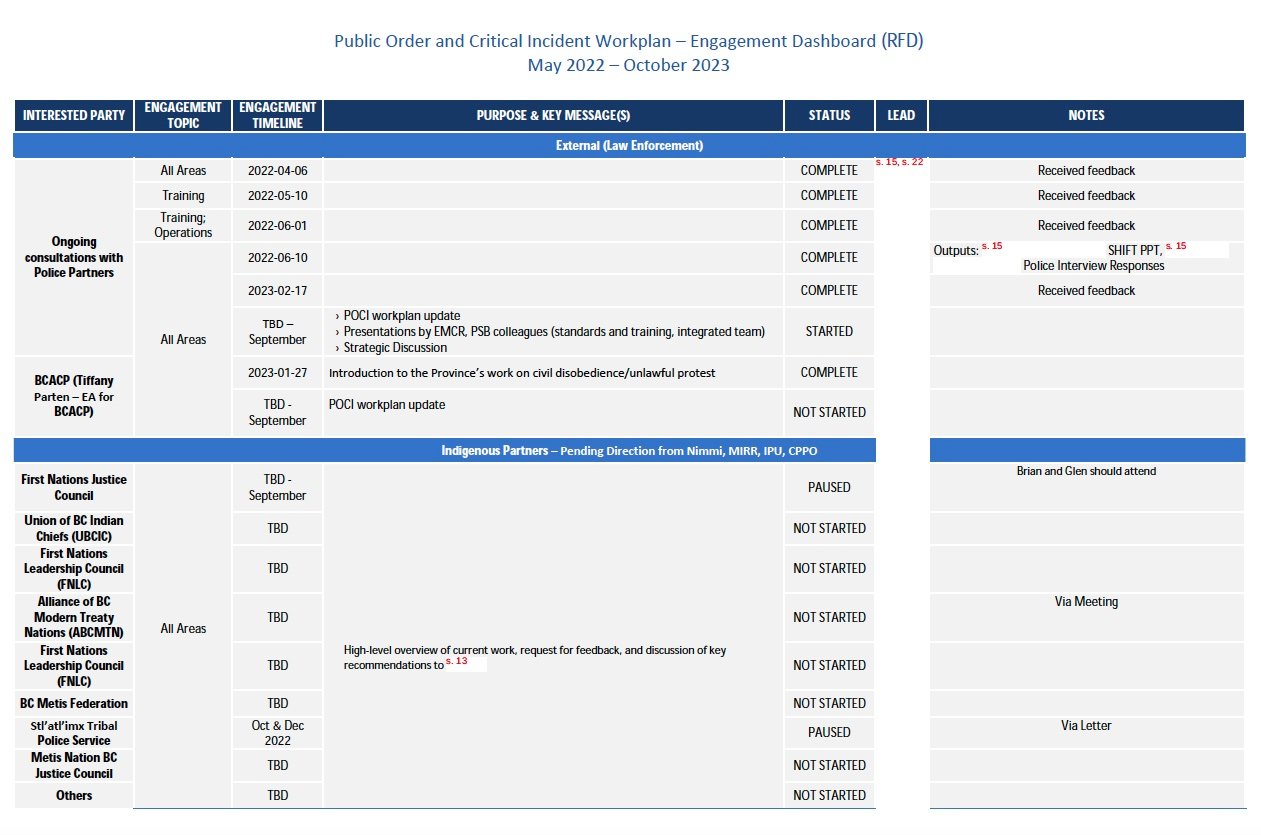

An “engagement dashboard,” which tracked tasks and timelines, shows that most engagement with police had been completed by early 2023, while discussions with most Indigenous organizations show a status of “not started.” In the case of the BC First Nations Justice Council, they were “paused.”

Earlier this year, The Tyee reported that concurrent efforts to bring the Police Act in line with the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act had stalled. At the time, the BC First Nations Justice Council confirmed that work on the Policing and Public Safety Modernization Initiative had been paused as the group sought clarity on the degree of co-development with the province.

The BC First Nations Justice Council told The Tyee last week that it had not been contacted by the province about the Civil Disobedience Work Plan. The Union of BC Indian Chiefs and the First Nations Leadership Council also said they were not aware of the project.

Jackson said the Civil Disobedience Work Plan’s framing of protests as unlawful doesn’t recognize a distinction between civil disobedience and Indigenous land defence.

“This is particularly troubling in a context like the Coastal GasLink project through Wet’suwet’en territory, because there is a Supreme Court decision [that] indicates very strongly that Aboriginal title exists,” Jackson said.

Secretive ‘Critical Incident Secretariat’ played role in plan

Records obtained by The Tyee also show that a mysterious arm of the provincial government’s Policing and Security Branch was involved in guiding the discussions.

The Critical Incident Secretariat is not mentioned on the B.C. government’s website and the Public Safety Ministry did not respond to a request for information about the department.

The secretariat provides “situational awareness throughout the province regarding protests pertaining to the natural resources sector,” according to the March 2022 briefing note. It was prepared by an unidentified author whose name and affiliation are redacted under sections of B.C.’s information and privacy act that protect personal information and law enforcement.

According to the briefing note, the Critical Incident Secretariat consists of an RCMP liaison and representatives from “several impacted ministries in the resource extraction, Indigenous relations and justice sectors.” It is funded and operated by the Public Safety Ministry and “has a contracted resource who maintains ongoing situational awareness” related to Fairy Creek, Coastal GasLink, the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion and “convoy style protests.”

The first task listed in the Civil Disobedience Work Plan was to “enhance” the Critical Incident Secretariat’s role within the ministry, starting with renewing the contract with the person leading the secretariat “for at least another term,” until March 31, 2023.

That person’s name is also redacted under sections of the act that protect personal information and law enforcement.

Documents released previously under freedom of information laws list Norm McPhail, a career Mountie who retired from the force a decade ago, as “project lead” for the secretariat.

Starting in 2020, the province awarded McPhail a series of contracts to “assume the central co-ordination role of high-priority project involving civil unrest activities,” according to a provincial list of directly awarded contracts. The province didn’t respond to The Tyee’s request for confirmation that McPhail is still leading the secretariat, but the list shows his contract was renewed in May and is set to expire in March.

“Information generated from the [Critical Incident Secretariat] and other sources is compiled and reported to Deputy Minister level committees,” the March 2022 briefing note states.

The Tyee recently reported that the province had violated its own privacy laws when it gathered personal information from Coastal GasLink about “various individuals” involved in the conflict over the pipeline.

In that case, the information was shared by B.C.’s LNG Canada Implementation Secretariat in a five-page email to an acting assistant deputy minister with the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation.

Jackson said the focus on information collection within the Civil Disobedience Work Plan — including the enhanced role of the Critical Incident Secretariat, which was attending regular meetings with industry and police in order to provide updates to senior provincial officials — “absolutely” raises concerns about privacy.

“We are generally concerned whenever we see surveillance of protesters,” Jackson said. “There’s an inherently political dimension to policing protests and we certainly see that there appear to be differential levels of police force applied to people with different causes.”

Jackson added that “networks of information sharing could potentially lead to information about people in Canada’s political activity being shared with intelligence agencies abroad through information sharing with federal-level police, the RCMP and CSIS.”

“That can go out to our Five Eyes partners and disseminate from there,” Jackson said, “and it’s hard to know what is being done with that information once it gets disseminated.” The Five Eyes is an intelligence alliance composed of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States.

This creates fear for people with loved ones overseas who could be impacted by their protest activity here in Canada, Jackson added. “It has a significant chilling impact on people’s ability to engage in political expression.”

BC silent on work plan outcomes

According to the March 2022 briefing note introducing the work plan, its intended outcome was to be “a cross-government plan with a range of policy and funding options for consideration by decision makers.” By fall 2023, the province intended to share a draft of an unspecified deliverable for feedback, according to the documents.

But it’s unclear where the process currently stands.

About half of the roughly 150-page document provided in response to The Tyee’s freedom of information request was withheld, and references to specific outcomes were redacted under a section of the act that protects government recommendations and policy advice.

The work plan’s timeline coincides with provincial efforts to make the RCMP’s Critical Response Unit — British Columbia, or CRU-BC, a unit formerly known as the Community-Industry Response Group, a permanent part of the province’s policing.

The unit, which was created in 2017 in response to Indigenous-led pipeline opposition, faces allegations of misconduct related to arrests on Wet’suwet’en territory and Fairy Creek protests.

It is currently the subject of a systemic investigation by the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission, the RCMP’s federal oversight body. Calls for its disbanding have come from as high as the United Nations.

Despite the controversies, the province has moved toward formalizing CRU-BC’s role in the BC RCMP.

The Tyee reported earlier this year that CRU-BC’s mandate had expanded from resource industry conflicts to encompass protests more broadly, with its officers most recently appearing at demonstrations opposing Israel’s war on Gaza. An RCMP spokesperson said at the time that the unit’s approach to public disorder had been adopted as a “national best practice.”

Civil Disobedience Work Plan documents appear to link the initiative with efforts to make CRU-BC a permanent fixture in the province.

A Nov. 21, 2022, PowerPoint presentation titled “Committee on Public Order and Critical Incidents” referenced a $36-million funding boost the province quietly allocated to the unit in late 2022. It noted that “temporary and seconded resources” were creating pressure on provincial and RCMP budgets.

“In September [2022], we were invited by the Treasury Board to advance a submission for the Community-Industry Response Group,” the presentation said, referring to the unit that is now CRU-BC. “We have been asked to provide options that will help address these challenges.”

Two days later, the province announced an additional $230 million over three years to rural policing.

Documents obtained by The Tyee through a freedom of information response released in early 2023 revealed that $36 million of the funding was earmarked for CRU-BC to “lead a consistent, integrated and impartially administered police response to unlawful protests and public order events across the province.”

A spokesperson for the Public Safety Ministry told The Tyee in March 2023 that the funds would be used to “standardize C-IRG within the BC RCMP, support deployment operations and response requirements, and put in place permanent funding for dedicated officers.”

The Public Safety Ministry didn’t respond to The Tyee’s more recent questions about whether CRU-BC had been tapped by the province to fill gaps identified by the Civil Disobedience Work Plan related to a dedicated protest response team and standardized police training.

The most recent development disclosed in documents provided in response to The Tyee’s freedom of information request is from earlier this year. In February, Brian Sims, the ministry’s executive director of the Serious and Organized Crime Division, signed off on a decision briefing note titled “Public Order Training Options.”

“Good note and discussion,” Sims wrote. “Change me to the signatory and I support option 1.”

The ministry did not respond to The Tyee’s questions about what the first option entailed or whether training related to public order had changed as a result.