Articles Menu

Industrial mining in the deep ocean is on the horizon. Despite several countries including Germany, France, Chile and Canada calling for a pause on the field’s development, the International Seabed Authority, the organization tasked with both regulating and permitting deep-sea mining efforts, is nearing the deadline to finalize rules for how companies will operate.

Companies, meanwhile, are busy testing the capabilities of their machines — equipment designed to collect polymetallic nodules, rocks rich in cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese that litter some parts of the seafloor.

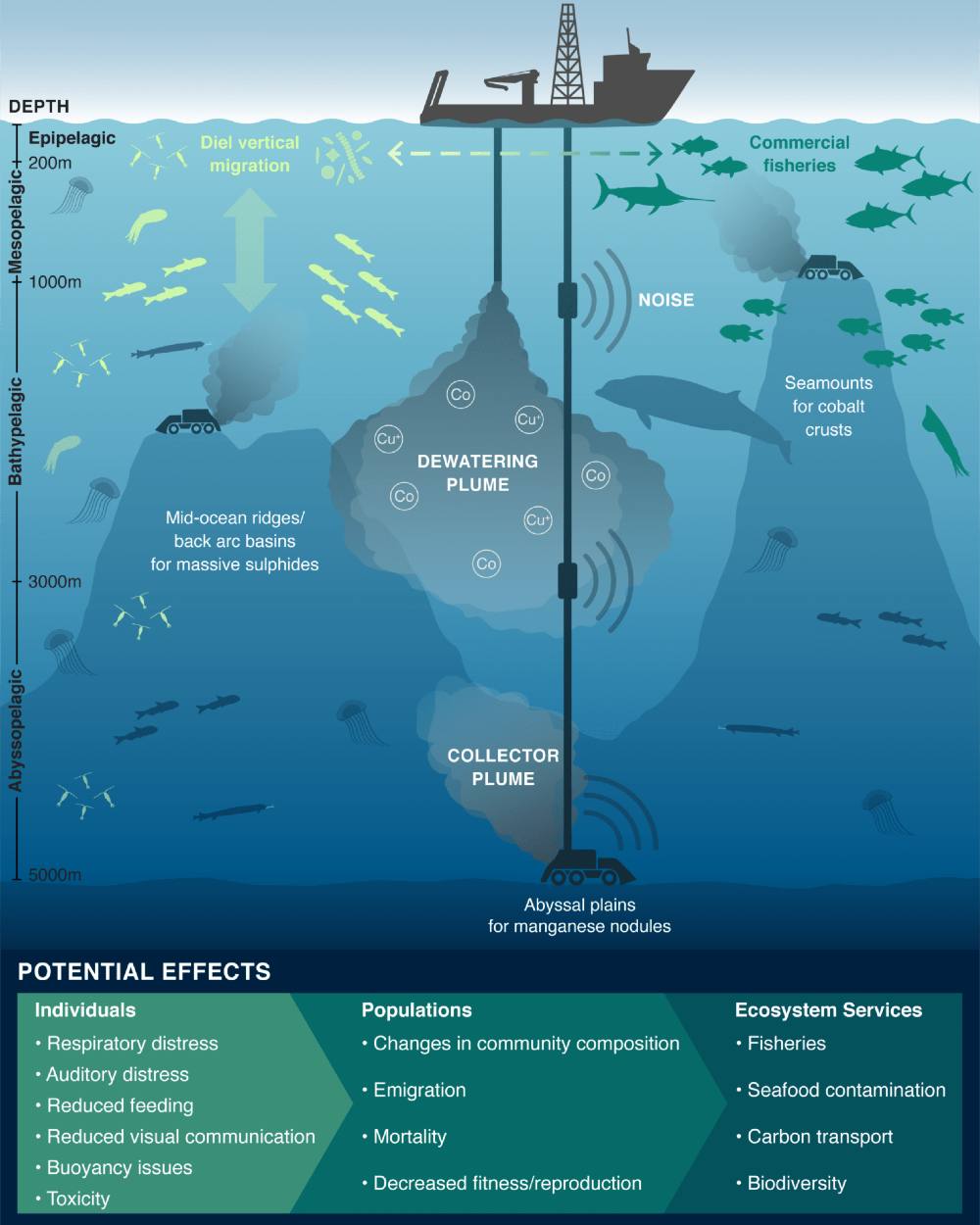

Top of mind for many scientists and politicians is what ramifications deep-sea mining might have on fragile marine ecosystems, including those far from the mining site. At the heart of the debate is concern about the clouds of sediment that can be kicked up by mining equipment.

“Imagine a car driving on a dusty road, and the plume of dust that balloons behind the car,” says Henko de Stigter, a marine geologist at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research. “This is how sediment plumes will form in the seabed.”

Scientists estimate that each full-scale deep-sea mining operation could produce up to 500 million cubic metres of discharge over a 30-year period. That’s roughly 1,000 six-metre-long shipping containers full of sediment being discharged into the deep every day, spawning from a field of mining sites spread out over an area roughly the size of Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium and Germany.

These sediment plumes threaten to smother life on the ocean floor and choke midwater ecosystems, sending ripples throughout marine ecosystems affecting everything from deep-sea filter-feeders to commercially important species like tuna. Yet discussions of the plumes’ potential consequences are clouded by a great deal of uncertainty over how far they will spread and how they will affect marine life.

To clarify just how murky deep-sea mining will make the water, scientists have been tagging along as companies conduct tests.

Two years ago, Global Sea Mineral Resources, a Belgian company, conducted the first trials of its nodule-collecting vehicles. Scientists working with the company found that more than 90 per cent of the sediment plume settled out on the seafloor, while the rest lingered within two metres of the seabed near the mined area.

Other studies from experiments in the central Pacific Ocean found that the sediment plumes reached as far as 300 metres away from the disturbed site, though the thickest deposition was within 100 metres. This is a shorter spread than earlier models, which predicted mining plumes could spread up to five kilometres from the mining site.

Beyond the sediment kicked up by submersibles moving along the seafloor, deep-sea mining can muddy the water in another way.

As polymetallic nodules are lifted to the surface, the wastewater that’s sucked up along with the nodules is discharged back into the ocean. Doug McCauley, a marine scientist at the University of California Santa Barbara, says this could potentially create “underwater dust storms” in upper layers of the water column. Over the course of a 20-year mining operation, this sediment could be carried by ocean currents up to 1,000 kilometres before sinking to the seabed.

Some particularly fine-grained particles could remain suspended in the water column, travelling long distances with the potential to affect a wide range of marine animals. According to another recent study, it’s these tiny particles that are the most harmful to filter-feeders like the Mediterranean mussel.

To avoid these consequences on midwater ecosystems, at least, scientists are advising would-be deep-sea miners to discharge wastewater at the bottom of the ocean where mining has already created a disturbance. This would be a departure from the ISA’s messaging, which is to not specify at what depth wastewater should be released.

For its own trials last December, the Metals Co., a Canadian company, says it worked hard to minimize the amount of sediment discharged in the wastewater it released at a depth of 1,200 metres.

“We’ve optimized our system to leave as much sediment on the seabed as possible,” says Michael Clarke, environmental manager at TMC. Clarke says he’s skeptical of previously published research projecting vast sediment plumes. “When we were trying to measure the [midwater] plume a few hundred metres away from the outlet, we couldn’t even find the plume because it diluted so much.”

Clarke says the company is currently analyzing both baseline and impact data for its test mining, including looking at how far small particles spread and how long they remain suspended. The results will be submitted to the ISA as part of an environmental impact assessment.

As deep-sea mining inches closer and scientists ramp up their research efforts, it’s important to keep one thing clear: “I can tell you that we’re not going to discover that deep-sea mining is good for marine ecosystems,” McCauley says. “The question is, How bad will it be?”

Elham Shabahat is a writer and researcher interested in conservation, cities, forests, and the climate crisis. Her work has been published by CBC News, Sapiens, Mongabay and others. This article was originally published by Hakai Magazine.

[Top photo: Scientists are concerned about how much damage sediment kicked up by mining equipment will do to seabeds and ecosystems closer to the surface. Photo via Shutterstock.]