Articles Menu

Aug. 15, 2025

We got rain — so our drought concerns are over, right?

It’s something we hear from readers, family and friends all the time. It’s a fair question. Drought warnings are becoming more common across Canada, and when we get a wet day, week or even month, we may think — or hope — that it’s solved the drought issue. But drought can be a compounding problem, even after the cool relief of rain.

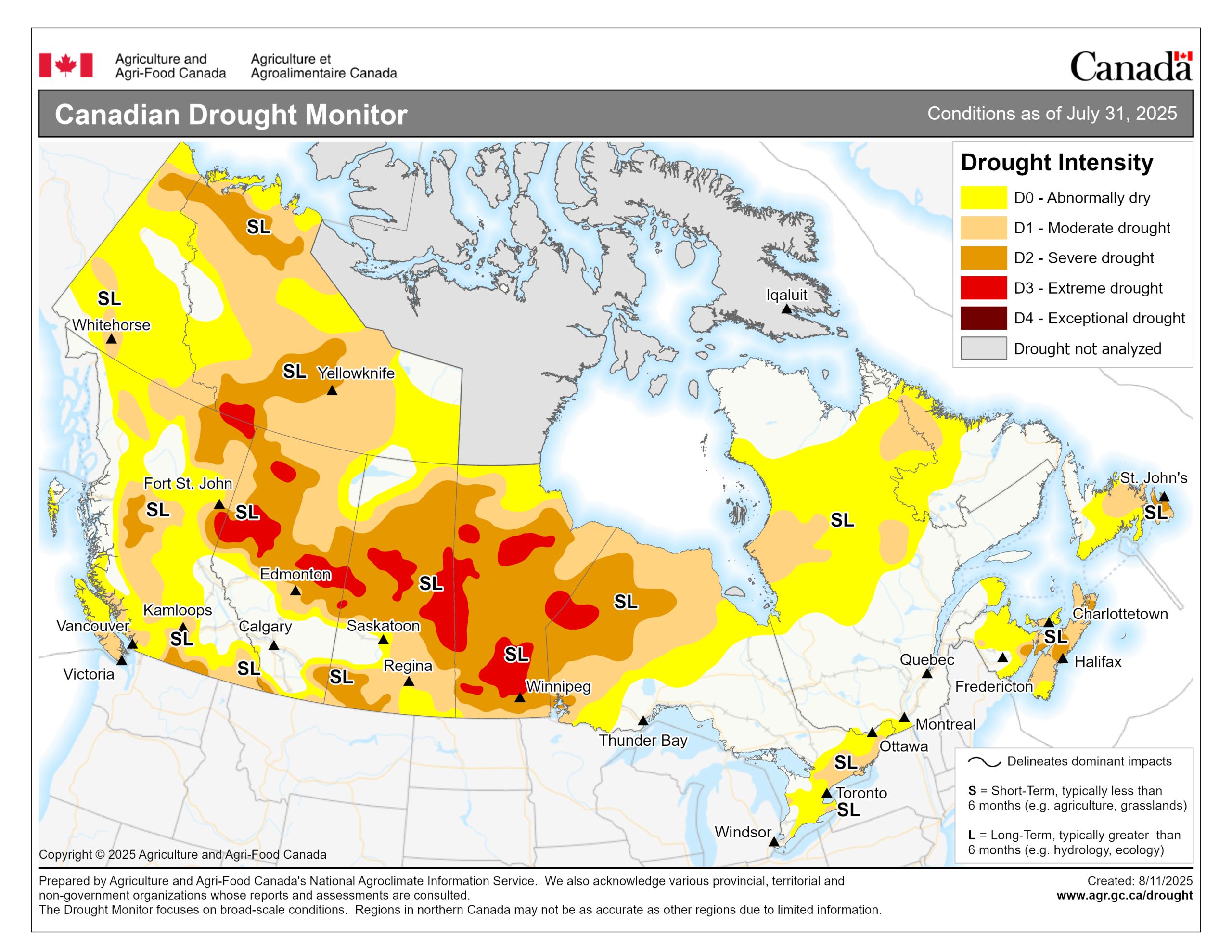

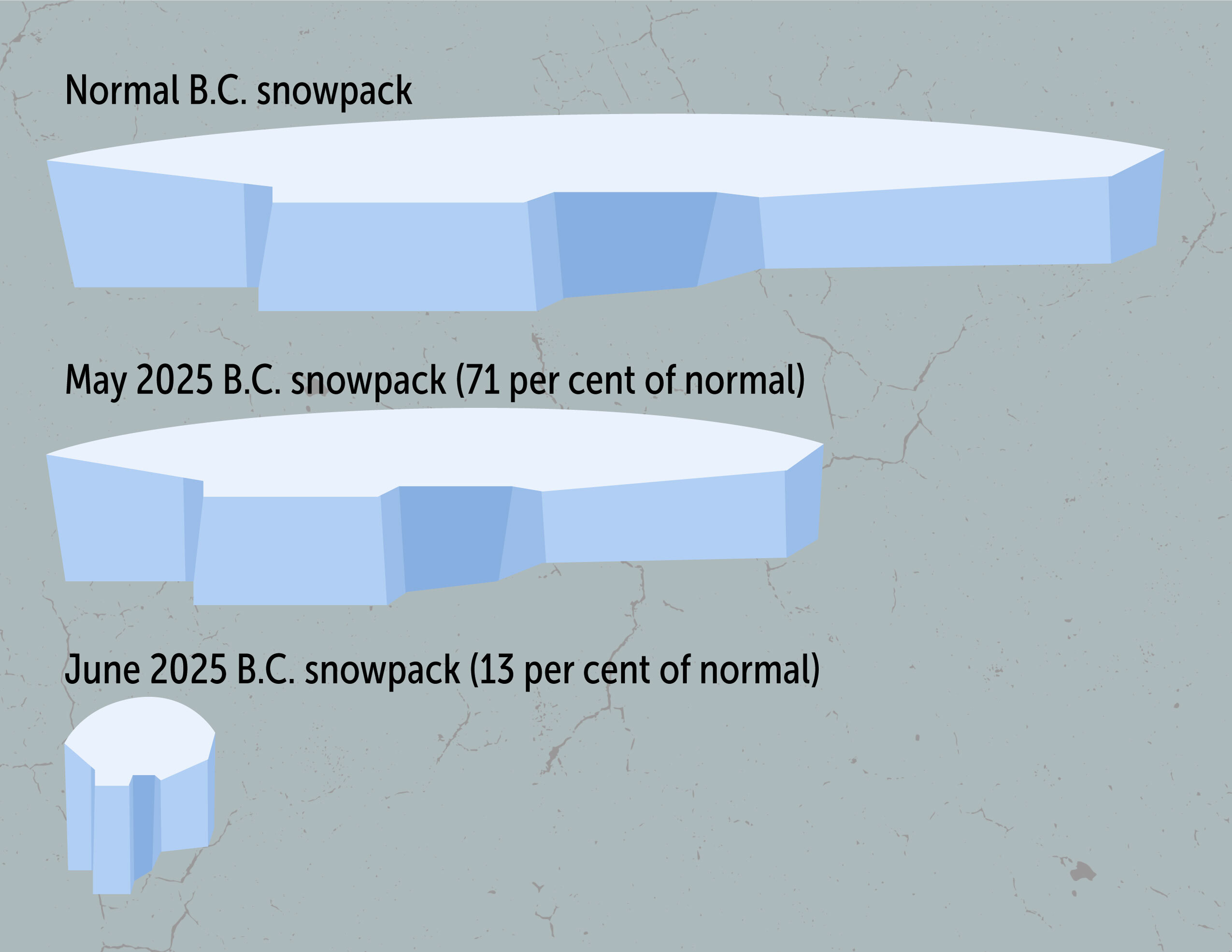

It’s an issue affecting forests, grasslands and coasts. According to the Canadian drought monitor, 71 per cent of the country was in drought as of July 31 and most of Canada had below-average precipitation in July. The government of British Columbia reported snowpack in May was 71 per cent of normal, but by June, that plummeted to 13 per cent of normal, with some areas at zero per cent of normal.

While some areas of Canada have received more rain than normal lately, others are receiving starkly less — like southwestern Saskatchewan, which received less than 25 per cent of typical rainfall in June. Several areas in the province have declared agricultural states of emergency.

Water scarcity is already an increasing risk, and even more pressures are growing. Donald Trump has called Canada a “very large faucet” that could be used to mitigate water shortages in the United States. And companies like Bell Canada are looking to open artificial intelligence (AI) data centres, which guzzle an incredible amount of drinking water, sometimes millions of litres in a single day for large centres.

Many Canadians may be surprised to hear they have no enshrined right to clean water. Residents of Glade, a small B.C. community, mounted a legal challenge against private logging near their water supply, and in 2019 a B.C. Supreme Court judge concluded they did not have any inherent right to this natural resource.

“Do you have a right to clean water?” Justice Mark McEwan said in court. “I’d suggest you don’t. There just is nowhere in the law where you can look and say, ‘There it is — there’s my right, I have a right to clean water.’ ” Canada recognized the UN declaration on the human right to safe drinking water and basic sanitation in 2012, but that is not a legally binding protection.

Many interests want to pull from Canada’s water — while drought already has caused major ecosystem and economic losses.

Crop insurance payouts in Canada ballooned in the past few years, ranging from $3.5 billion to $4.9 billion between 2021 and 2024. For the decade before that, between 2010 to 2020, payouts ranged from $77 million to $1.7 billion. Farmers in the Atlantic provinces have said this year’s drought is the worst in recent memory, decimating both their crops and their livelihoods.

Drought can also interfere with hydroelectricity generation, making electricity more expensive — B.C. and Manitoba had to import power in 2024 due to low reservoir levels.

Drought can’t only be understood in terms of lack of rain — it’s how water is functioning in the whole system, Younes Alila, professor in the University of British Columbia’s department of forest resources management, previously told The Narwhal. In a recent short documentary, Trouble in the Headwaters, he explains how logging has contributed to increased risk of flood and drought by removing tree cover that keeps the ground moist and cool, moderating the speed of melting snow.

“When the snowmelt’s slower, it has a chance to infiltrate into the soil, recharging the groundwater,” he explains in the film.

Without trees, water can rush down slopes, causing flooding and landslides, he says. “This is why we are going to be living under a heightened risk of flooding and droughts for decades to come — because by nature, the recovery is very slow.”

Many wetlands that retain water and mitigate floods have also been cleared for human development. That means soil is more likely to dry out, so it also doesn’t absorb water as well.

Hotter weather exacerbates drought risk by causing more erratic precipitation and earlier, faster snowmelts than normal — and the sudden flows can all wash away over the dry soil rather than getting soaked in.

It’s similar to pouring water on a dried-out potted plant; the parched soil doesn’t absorb the water, and it runs out the bottom of the pot instead.

As the climate changes, bringing higher temperatures and drier conditions, drought conditions spread and worsen. The impacts are widespread, even if they’re felt at different times to different degrees.

It may be tempting to not worry about lower levels of drought, but the effects can still branch outwards. B.C. classifies drought severity by levels 0 through 5, going from normal to severe and rare. In the B.C. Interior, much of the area is at Level 2 drought, midway through the scale. But some rivers are low and warm enough already to risk aquatic life like salmon, which rely on cool temperatures.

When plants dry out in drought, it can mean less shade and shelter for animals like ground-nesting birds, as well as less productive growth of nuts and berries for deer and bears, or less lichen for caribou. That can force animals to move in search of food and water, sometimes to urban areas.

Drought comes with human health risks, too. According to the Canadian Climate Institute, drought can degrade water quality and promote algal blooms — which are increasingly common in Ontario’s Great Lakes — and waterborne diseases. Meanwhile, dusty conditions can worsen respiratory problems.

The push to build data centres across the world will put significant pressure on water supply — a Bloomberg investigation found that two-thirds of AI data centres globally are built or planned in places with high water stress. Much of that stress is due to other industries: AI currently uses much less water than, say, mining, but the race by Alberta and other provinces to attract new centres means the water they use is increasingly significant.

In B.C., Bell plans to build six AI data centres, while Telus plans to launch an AI “factory” in Kamloops, touting the project as something that can bolster Canada’s sovereignty in the face of U.S. tariffs and threats of annexation. Bell’s first data centre is also planned for Kamloops, and the next in Merritt, both in B.C.’s dry Interior.

Merritt is in the Nicola watershed, which is in Level 3 drought. The nearby Coldwater River is having such low flows it is not meeting the needs of salmon, a 2025 study from the Raincoast Conservation Society and Scw’exmx Tribal Council found.

“The Nicola watershed is one of B.C.’s most vulnerable regions to the effects of climate change, particularly as it relates to drought,” Raincoast said in a release.

Meanwhile, in Ontario’s Great Lakes region — which provides water to 70 per cent of the province’s 14 million people — there are at least 108 data centres in the Greater Toronto Area alone.

Data centres use cold water to cool their computers — and they use immense amounts. One study projected global AI demand will withdraw between 4.2 and 6.6 billion cubic meters of water in 2027. That’s more than Canada’s entire manufacturing industry used in 2021. And demand is only growing.

In Newtown Country, Ga., where tech giant Meta built a data centre, the cost of water has soared, with rates set to increase 33 per cent over the next two years, and the county is on track to be in a water deficit by 2030, the New York Times reported. Meta makes up about 10 per cent of the county’s total water use every day.

In Spain’s Aragon region (home to about 1.3 million people and a bit bigger than Vancouver Island), Amazon’s new data centres are predicted to double the entire region’s current electricity use, and the company is asking to increase its water consumption by 48 per cent.

AI has the ability to increase our efficiency and better monitor our use of natural resources — but its water consumption is on track to outweigh its environmental contributions, three professors from the University of Amsterdam recently argued in The Conversation.

These centres are draining groundwater while “the minimum needs of the world’s poorest to access water and sanitation services have not been met,” they argued, adding that Google’s data centres used over 21 billion litres of drinkable water in 2022, up 20 per cent from 2021. Each year, the computing power used for AI increases.

“We believe there is sufficient evidence for concern that the rapid uptake of AI risks exacerbating the water crises. … As yet, there are no systematic studies on the AI industry and its water consumption,” they concluded.

Unlike the European Union, Canada doesn’t have water use disclosure rules for data centres — in part because water is managed provincially, not federally.

The B.C. non-profit organization Watershed Watch reported this summer that industrial water users in the province pay a maximum of $2.25 per million litres, a rate that hasn’t increased in a decade. In Ontario, the rate is just $3.71 for the first million litres, with commercial water bottlers paying an additional $500 per million litres.

But industries use billions of litres of water — mining company Rio Tinto used 72.5 billion litres of water in Quebec in 2022 alone. According to the Montreal Gazette, businesses used 800 billion litres of water in the province in 2021 and paid just $3 million, a number the provincial government cited when it increased commercial water rates 900 per cent last year.

Watershed Watch suggests raising industrial water rates and using that revenue to support watershed security. It suggests that revenue could also go to developing regional watershed boards made up of “First Nations, governments, farmers, non-profits and other stakeholders to manage water locally.”

The non-profit says B.C. sounds “like a broken record” telling residents to “take shorter showers and water their lawn less,” and that while these steps are important, it’s an “unserious solution to a very serious problem.”

“We’re not asking for a radical solution, just a responsible one. The status quo is failing our salmon, our watersheds and everyone who calls B.C. home.”

First Nations disproportionately lack access to clean drinking water, and drought exacerbates the issue. Some First Nations have been left waiting years to get access to clean water. Tallcree First Nation in northern Alberta relies on spring runoff to pull water from a nearby creek, and it told the CBC it’s concerned when flows are low, it won’t be able to pull anything.

In 2015, former prime minister Justin Trudeau promised to end long-term boil water advisories in First Nations by 2021. As of July 11, 38 advisories remain in place. But the feds specifically define “long-term” as a single advisory lasting more than one year — so communities that experience many “temporary” boil water advisories for weeks or months at a time are not included. The federal government also does not track advisories in B.C. First Nations.

First Nations access to clean water is a painfully long-standing issue, which has been condemned by multiple United Nations representatives over the years — and yet, some Canadian politicians are still opposing a First Nations clean water bill.

Meanwhile, drought conditions can also exacerbate wildfires, which have hit the Prairies hard this year. Almost 69,000 square kilometres in Canada have burned — making this Canada’s second-worst wildfire season on record so far. More than half of all areas burned in 2025 are in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

If that surface area was instead one of the Great Lakes, it would be the second biggest one behind Lake Superior and ahead of Lake Huron. If it was an island, it would be twice as big as Vancouver Island.

Manitoba had a dry spring followed by an unusual spring heatwave, contributing to the devastating fires that caused thousands to be evacuated.

Again, Indigenous people are being disproportionately affected by evacuations.

“This will be the largest evacuation Manitoba will have seen in most people’s living memory,” Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew said in May.

Last year, when Alberta was dealing with low water supply, Tricia Stadnyk, a professor of engineering and geography at the University of Calgary who studies hydrology, told The Narwhal Canada as a whole has ignored what’s coming.

“Oh, it’s Canada, we have so much water we don’t know what to do with it, we’re never going to have drought that’s so severe people have to move or can’t survive or we can’t grow crops,” she says, summarizing the common belief that massive, widespread water shortages can’t happen here.

“It’s just unthinkable for Canadians to think about drought at that scale, but the reality is this is the future of the Canadian Prairies.”

“Unless properly managed, even Canada’s water supplies will eventually run out,” Stadnyk wrote in The Conversation earlier this year.

She calls for more data collection so we can forecast water flows better, and for improved cooperation across municipalities, provinces, Indigenous governments and the feds, along with the United States at transboundary areas. She says the current system has “fragmented oversight” and “privileged licences” for industrial users that shows “little care” for watershed health. She advocates for improved water efficiency by industrial users, along with people curbing their individual use.

“It’s time to challenge our wasteful ways and accept that even in Canada, water must be managed effectively,” she says.

“The choices we make today will impact our children and their children and will literally mean the difference between them thriving or surviving as a society.”