Articles Menu

Mar 26, 2021

22 min read

Simon Frankson emerged from his sleeping bag at 4 a.m., just in time to join the fray.

The day before, a balmy afternoon in early August, he and about a dozen campers had studied a satellite photo of the area: a mountainside sheathed in deep green cedars and Douglas fir trees, many of them hundreds or thousands of years old, in a watershed known as Fairy Creek in the southwest corner of Vancouver Island. The telling grey stripe of a logging road was creeping up from the left side of the image. It was the same kind of road that has, over the past century, made way for logging companies to cut down 80 per cent of the ancient forest on an island larger than Belgium.

When Frankson and the campers had arrived the night before, things already looked different than in the photo. The stripe had grown into a web of roads advancing up and across the slope. One more day and the machines could crest the ridge above them, opening up yet another valley to industrial logging.

Now Frankson was rubbing the sleep from his eyes and readying himself for his first shift as an old-growth forest blockader. Out of the blackness, the harsh headlights of a four-by-four came swerving around a switchback toward the camp. Frankson jumped up to join the line of bodies rushing to stand their ground. The driver, a contractor for the Teal-Jones timber company, killed the gas. For two long minutes, they faced one another, frozen. Then, as if concluding an unspoken conversation, the truck slowly reversed down the mountain.

Now an injunction application by Teal-Jones threatens to break what’s been building over the past eight months. On April 1, the B.C. Supreme Court will decide whether to grant the injunction and authorize arrests. But the blockaders have already declared a “last stand for ancient temperate rainforests” no matter the costs.

In a world wracked by climate change and species loss, the Fairy Creek blockaders occupy a desperate frontline. But like the speed of industrial logging, slap-dash movements like this one have consequences. Urgency saves trees but it can alienate allies. While environmentalists are making more effort to work with local First Nations that share similar goals, Fairy Creek is a reminder that it’s not always easy. Pacheedaht First Nation, whose territory includes the watershed, has long relied on old-growth logging. But the nation is at a crossroads when it comes to the future of its forests.

The blockaders are racing not only to stymie the plans of Teal-Jones, but to forge deeper connections with potential new allies. It’s not clear what the showdown in court will set in motion. Will an injunction scatter the blockaders? Or might it accomplish what they hope — a heightened awareness of their fight, catalyzing the kind of broad, even international, support that fuelled British Columbia’s previous War in the Woods?

Pacheedaht First Nation, whose territory includes the Fairy Creek watershed, has long relied on old-growth logging. Photo: Serena Renner

The initial calls to defend Fairy Creek came via email and Zoom from a 17-year-old in Union, Wash. named Joshua Wright, who grew up visiting the cedar and hemlock groves of Vancouver Island as a kid.

The blockade came together in days, but it was a response to decades of government inertia when it comes to protecting old-growth forests. Despite promises to implement recommendations of a 2020 report that advises deferred logging in the most at-risk forest ecosystems within six months, the NDP government has failed to make any concrete changes.

The dirt road to Fairy Creek’s Ridge Camp shows the scars of this inaction. Clearcuts — large areas of forest razed for timber — create a camo-print collage that stretches across the territory of Pacheedaht First Nation toward the small town of Port Renfrew, two hours northwest of Victoria up a winding coastal road. Old-growth logging is happening all around here, but the blockade has mainly kept its focus on the 2,000 hectares of rainforest around Fairy Creek, a tributary of the San Juan River. It’s the largest swath of unbroken old-growth forest in the region outside of a park.

The forest in the Fairy Creek watershed. Photo: Serena Renner

The location of Fairy Creek near Port Renfrew on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Map: Zoë Yunker

“Old growth” is a simple term for complex ecosystems that have evolved over long periods of time and are home to thousands, if not millions, of plant and animal species. Their multi-storied canopies are often compared to cathedrals for the way they filter light between columns of trees that range from saplings to prehistoric giants. The province’s definition for coastal old growth is a forest containing trees more than 250-years-old.

Coastal temperate rainforests, like the moss-laden landscapes of Vancouver Island, cover less than one per cent of the planet. They purify air and water; shelter salmon, cedar and medicines integral to First Nations; and cool down regional climates by producing a near constant drizzle. The most biologically productive of these forests — those with the greatest variety of species and largest trees — gulp and store more carbon than any other above-ground environment. Their structure and diversity also means they’re less vulnerable to fires, floods and natural disturbances. In other words, they’re one of our best defences in the fight against global climate change.

B.C., though, has historically depended on old-growth logging, which took off on Vancouver Island around the 1920s and was the economic backbone of towns like Port Renfrew. Half a century later, industrial-scale forestry galvanized a wave of opposition. In the early 1980s, Indigenous communities and environmentalists began to recognize the scale of losses and set up Canada’s first logging blockade on Meares Island, a 30-minute boat ride from Tofino in Clayoquot Sound, Tla-o-qui-aht territory. The effort, which combined direct action with Indigenous court cases, led to the protection of Meares Island in 1985.

But the clear cutting continued. By the early 1990s, just 30 per cent of the Island’s original forest and a fraction of its watersheds remained unlogged. Roadblocks, tree sits and encampments spread across the Island, culminating in 1993 with the Clayoquot Sound protests that came to be known as the War in the Woods. Nearly 900 people were arrested that summer. It’s still considered one of the largest acts of nonviolent civil disobedience in Canadian history.

Yet today, the Island is down to 20 per cent of its original ancient forest. And only around three per cent of that is estimated to be the most productive valley bottoms with the biggest, oldest trees.

About a dozen Fairy Creek blockaders arrived in August and have stayed throughout the winter. Photo: Will O’Connell

“I couldn’t believe we were still logging old growth,” says blockader Shawna Knight. “At the rate that resource extraction happens in B.C., if we don’t stand up and do something right now, there will be nothing left.”

In October, the Fairy Creek Blockade moved its headquarters down closer to sea level for winter as Teal-Jones packed up for the season, instead focusing its timber cutting on more accessible forests a few ridges north in the Caycuse Valley. But there was never any doubt that come spring, the company would return.

“All the work that we’ve done and everything we’re trying to protect could be compromised very quickly,” says Suzanne Tripp, a 23-year-old Indigenous studies major at Camosun College in Victoria. “It’s kind of hard to grasp sometimes.”

Tripp got involved about a month into the blockade, arriving like many do as a curious activist. Born to a Métis mother and settler father on the southeast Alberta plains, Tripp admits that she’d never seen a massive tree until arriving at the blockade. “I came up here fully caring about the trees and fully willing to get arrested for them, and then I actually saw one,” she says. “I was shook.”

Shawna Knight first discovered the movement through a Facebook post. She recognized the name Fairy Creek having raised her two teenaged kids in the area. Before that, she thought the Island’s old growth was already protected. “I’ve never done anything like this,” she says.

A purple scar peeks out from the neck of Knight’s jacket — a trace of the rounds of thyroid cancer she’s survived. That experience sparked a hard-won reorientation: “You just accept your part of what’s meant to be and what is.”

Since showing up a few weeks into the blockade, Knight’s been at Fairy Creek almost every day, transporting supplies and patrolling logging roads in her black pickup. She temporarily shut down her food truck to be here. “I can see why people don’t do this. There’s no financial benefit, no security,” Knight says. “It strictly grows your heart. That’s all you get.”

Shawna Knight has been a mainstay at the blockade, transporting supplies and patrolling logging roads in her black pickup. Photo: Serena Renner

The blockaders’ main strategy has been a simple one: stop the logging trucks from getting in. “It only takes three people to stop equipment and build a blockade,” says Knight. “Even one person can really change things.”

Fairy Creek was always meant to be just the beginning. It’s significant as the last intact valley on southern Vancouver Island, but it’s only 2,000 hectares and about 40 per cent of that is already protected as old-growth management or wildlife habitat areas. For a while, the group debated calling their campaign the “Old Growth Blockade” to signal loftier intentions to defend forests throughout Vancouver Island and beyond. While it was the Fairy Creek moniker that stuck, the spirit of bigger ambitions prevails. “We’ll just sort of bug out to blockades and scatter along the hillside as needed,” Knight says. A few core blockaders affixed a seal with the words “Rainforest Flying Squad” to their trucks, establishing their self-appointed role as forest wardens. They have since established three more camps to defend other forests nearby.

Perhaps paradoxically, a broader movement to protect old growth, mainly composed of non-profit groups with roots in the 1990s protests, already exists — but has a different strategy. Organizations like the Ancient Forest Alliance and the Wilderness Committee have spent years meeting with logging communities, faith groups and governments in an attempt to target the economic and political barriers to old-growth protection.

Valerie Langer knows those barriers well. She was a central figure on the Clayoquot Sound blockades in the late 1980s and early ’90s, and was arrested and jailed multiple times. Leading up to the famous protests of 1993, Langer and her fellow activists came to a sobering realization. “We were not a big enough voting bloc, and we weren’t organized in any powerful way,” she says. “Strategically, the problem was that we were trying to bend the ear of a government that didn’t really care about the small voices in a wilderness area, on the far coast of B.C.”

They reached out to groups with bigger audiences like Greenpeace and the Sierra Club in the U.S., and organized a global boycott of B.C.’s old-growth products. “We realized that being right isn’t the point if you lose what you’re trying to win,” she says. That meant partnering with groups that had different, less radical, ideas of what needed to happen. In the end, the efforts helped establish a scientific panel, new logging regulations, and a co-management arrangement between the B.C. government and local First Nations.

Langer sees blockades as vital but limited in their effectiveness. While she recognizes the urgency of the times, she believes direct action must be embedded within a larger strategy. “If we want to create bigger systemic change, then you have to have both the radical action and the long-term game happening in parallel.”

“People who care about this issue care so deeply, and haven’t had an outlet for so long.”

But despite more than 30 years of campaigning with bursts of direct action, B.C.’s old-growth forests are in more danger now than ever. “The point of the blockade,” says 29-year-old activist Will O’Connell, “is not to wait for the non-profits, and not to let them keep leading us because I don’t see that building or moving somewhere.”

Sophisticated strategy is also a luxury the blockaders can’t afford. They’re stretched thin just keeping the camps dry and managing the stream of characters bubbling in and out of Fairy Creek. The movement is the product of whoever shows up that day. “It’s constantly crumbling and growing at the same time,” says O’Connell.

As the months have worn on, the blockade has attracted some institutional support. The environmental non-profits Stand.earth and the Wilderness Committee have become more involved and now keep their members informed about Fairy Creek while clarifying their independence.

Still, the blockade remains fervently grassroots and non-hierarchical. This kind of open structure means that just about anyone can come with an idea and execute it. It’s been an empowering experience for many new activists who have found a role at the blockade. “I wanted to get into the environmentalist movement like six years ago, and I kept emailing organizations and was constantly filtered into letter-writing campaigns and giving money. The more organized you are, the harder it is to find a niche for someone,” O’Connell says. “People who care about this issue care so deeply, and haven’t had an outlet for so long.”

A cold October rain thumped on the tin roof of the camp kitchen as Knight boiled water for tea. The blockaders were waiting for Bill Jones, an Elder from Pacheedaht First Nation, whose territory includes the Fairy Creek watershed. So far, Jones has been the only member of his nation actively involved in the movement.

The Fairy Creek watershed is one of the last unlogged watersheds on Vancouver Island, thus adding to the urgency of protestors who want to protect B.C.’s remaining old-growth forests. Photo: TJ Watt

The issue of Indigenous consent has been a challenge for the blockaders since the beginning. Frankson recalls sitting on the forest floor at Lizard Lake near Port Renfrew alongside other activists discussing whether to blockade without the support of Pacheedaht First Nation. Messages sent to the band council and Jones the day before had gone unanswered.

After about 15 minutes of conversation during the meeting, urgency ruled the day. “Ultimately, I felt it was important enough to block the road,” says Frankson. “They were taking down ancient cedar trees. It was a dire circumstance.”

That group’s decision became a lightning rod for criticism, on the ground and online. Without the consent of the Pacheedaht, blockaders appeared to be reproducing an age-old mistake that had cut deep rifts in B.C.’s environmental movement: settlers claiming authority over land that doesn’t belong to them.

Before smallpox introduced by European settlers devastated their population, the Pacheedaht were estimated to have 1,500 members or more. Now there are only about 290 members — and 100 or so live on reserve near Port Renfrew. And for over a century, large corporations have liquidated the nation’s old growth.

Today, a revenue-sharing agreement with the province means that the nation is compensated for logging in its territory, including in the proposed cutblocks of Fairy Creek. Article 11 of that agreement indicates that the Pacheedaht are beholden to “non-interference”: they can’t “support or participate in any acts that frustrate, delay, stop or otherwise physically impede or interfere with provincially authorized forest activities.” Some Fairy Creek blockaders believe that agreement means the Pacheedaht band council is legally barred from supporting the blockade, even if it wanted to.

But the council isn’t opposed to old-growth logging. A few years ago, they built a multimillion-dollar sawmill specifically designed to process old-growth cedar. Every year, it mills 10,000 cubic metres of wood — picture four Olympic swimming pools filled with logs. In 2010, the nation bought into a logging partnership that purchased a tree farm license covering 20,240 hectares south of Port Renfrew and Fairy Creek, some of which is old growth.

“We just watched logging trucks go by out of our territory,” said Pacheedaht band council Chief Jeff Jones in an interview with Ha-Shilth-Sa newspaper. “Now we’ve got tenures in our traditional territory with revenue coming back.”

Other Pacheedaht members have started voicing concerns about their old growth, and the species it supports like salmon. Arliss Jones, the former Chief of the nation, says old growth shouldn’t be clear cut, especially when there’s second- and third-growth forest around. “Just leave the first growth alone,” she says.

But she understands her nation is in a difficult position — stuck between the logging booms of the past and a new generation with different prospects.

“Our fathers were all loggers,” Arliss says. “If we didn’t have those jobs in our community, I don’t know how they would have survived. But this generation, it’s changed. We’re not that community anymore.”

Arliss also recognizes the challenge facing the band council when it comes to Fairy Creek. “Their hands are tied,” she says, because of the nation’s involvement in logging industries that rely on old growth. But she also critiques the council for not providing information about forestry issues to Pacheedaht members.

“We’re playing the guessing game between all these protesters and where Pacheedaht stands, and we stand in the middle,” Arliss says. “So maybe things didn’t happen perfectly. Nothing ever happens perfectly. But I’m grateful that the protesters are there to protect the territory against these huge logging companies.”

In response to an email, Rod Bealing, the forestry manager for the band council, declined to comment but acknowledged that internal work needs to be done. “Our nation currently takes the view that we need to continue to make it a higher priority to improve forestry-related communications within our community before we engage with external interests.”

Pacheedaht is in the final stages of a 25-year joint treaty process with neighbouring Ditidaht First Nation to reclaim tracts of their territories. So far, the band council’s silence has been interpreted by the blockaders as a tacit, if limited, form of consent for their actions. This assumption drew criticism from Indigenous leaders in Victoria, who called out the decision to occupy the ridge without having forged relationships with more members of the Pacheedaht community first.

These kinds of dilemmas — searching for common ground versus frontline action to keep trees from falling — informed Ken Wu’s work as co-founder of the Ancient Forest Alliance. A former campaigner for the Wilderness Committee, Wu was a student organizer during the Clayoquot Sound blockades. Then he noticed how direct action by environmentalists was polarizing them from loggers and energizing a pro-old-growth-logging countermovement. Wu began organizing across interest groups.

Wu’s top priority lies in finding economic alternatives to old-growth logging for First Nations. “Conservation financing needs to be front and centre,” he says.

He helped create a joint resolution with the Union of BC Indian Chiefs to call for government action to finance initiatives such as ecotourism and Indigenous Guardian programs that provide jobs while preserving the forest. Arliss says she would support these kinds of programs.

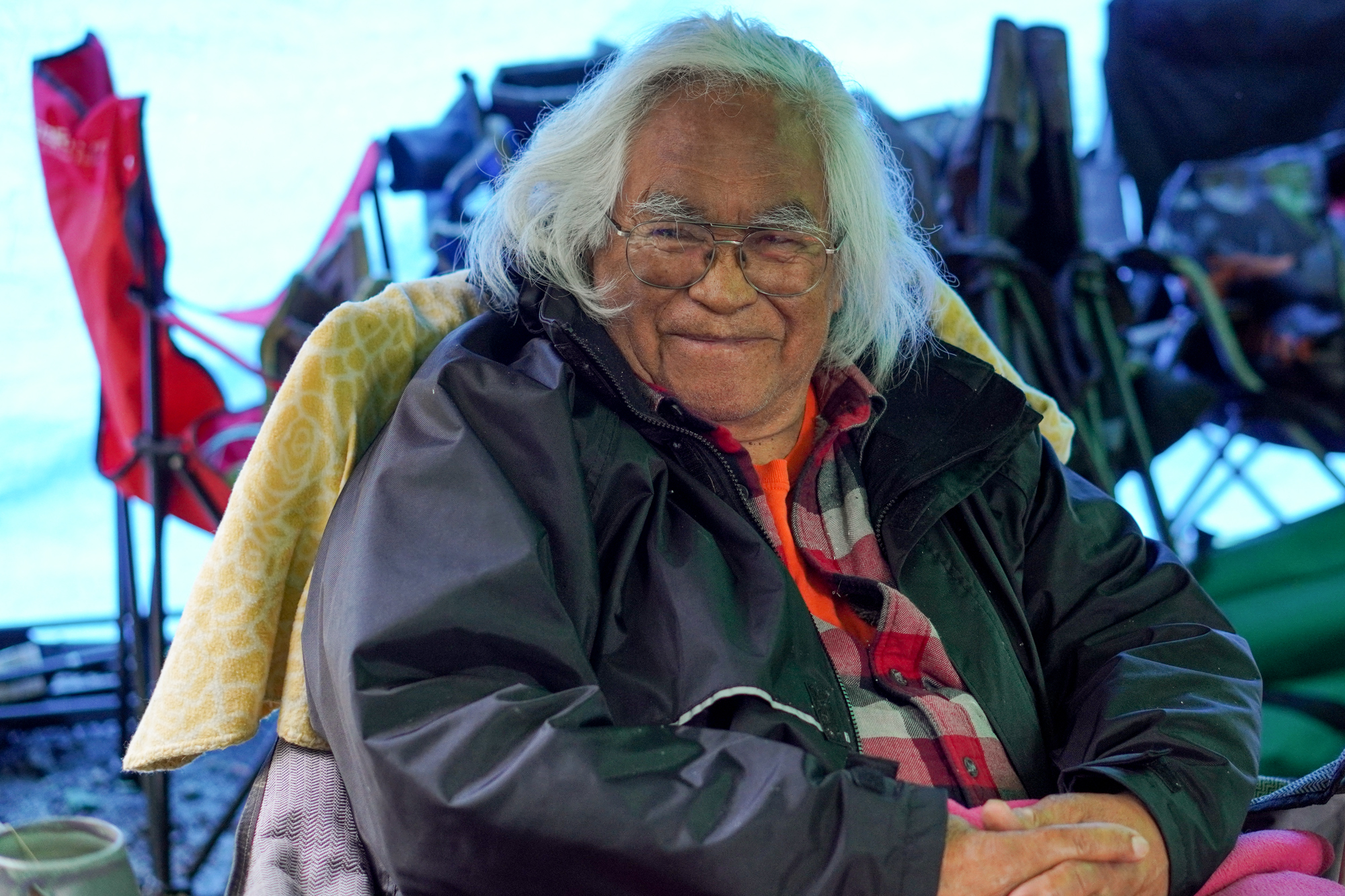

Bill Jones arrived at camp midday. Shawna Knight greeted the Pacheedaht Elder at his car and they walked arm-in-arm slowly to the fire. He sat in a fold-up camping chair, nodding at blockaders as they came and went from the circle forming around him.

Now 80-years-old, his hair wispy and white, Jones survived residential school in Port Alberni. He worked as an airplane mechanic, a nurse, and then a logger during the industry’s heyday of the 1960s and ’70s before getting laid off. “Every year, we would notice the patches of bareness, until after maybe 15 to 20 years, practically half of the forest was gone.”

Pacheedaht Elder Bill Jones has been the only member of his nation actively involved in the movement. Photo: Serena Renner

Jones says he was despondent in his early 70s, feeling the weight of colonization and environmental destruction. Then he got involved with forest activism in the Walbran Valley nearby. “I think I was ready for it. I was searching.”

In August, a week into the blockade, he joined the effort to protect Fairy Creek.

This day, his hands clasped and unclasped as he spoke to the intent blockaders. “I feel that we are now in a crucial process of surviving this storm.”

Jones has been careful not to blame his nation for inaction on Fairy Creek. “How do we reconcile the fact that not everybody in this community is on board?” he wrote in an open letter posted to the blockade’s Facebook page last September. “Who do we look to for guidance? There is no simple answer to these questions. We all have a role and a part in this and we need to appreciate and honour our differences. Difference is a good thing.”

Lisa Small, a 30-year-old blockader from Victoria, thinks their movement poses an open question about the future of settler activism. “It would be so powerful if this movement was Indigenous-led, but does that mean that it shouldn’t exist because it isn’t? I don’t know. We’re still trying to figure that out. What should it look like for settlers who want to take a stand?”

Tsastilqualus Ambers, an Elder from Ma’amtagila territory in Alert Bay, went to camp after hearing concerns about the blockade’s lack of Pacheedaht support.

She visited Ridge Camp in late September with her son and three Indigenous women, one of whom is Jones’s niece. They marched up the logging road toward the blockaders, drumming. When they got to the fire, they introduced themselves one by one, tracing their lineages, and then asked the blockaders to do the same. “After everything was done, we turned it over and explained to them that they have now introduced their ancestors to ours,” Ambers says, adding that this is the kind of relationship-building that should have happened before the blockade began.

“Nothing about us without us: that’s one thing a lot of environmentalists need to know,” she says. “You can’t call us to the table after you’ve formed an idea or a plan. We’re not an afterthought.”

For Bill Jones, the stillness of the forest has been a “touchstone” in his journey back to himself and his culture. As a kid, he paddled with his parents up near Fairy Creek, where they would camp on the beach. He’d wake to the smell of his mother barbecuing fresh sockeye salmon in the morning.

One day, years later working as a logger, he stopped and looked at all the cut trees at a log storage facility on Alberni Canal.

“I got halfway to the boom, and something hit me,” Jones recalls. “I don’t know what it was. I sat down and I started crying.” He says he suspects his fellow loggers had similar experiences. “Our training systematically alienates us from ourselves,” he says. “Desensitizing man is a very easy thing to do. And resensitizing him is very difficult.”

Jones’s story reflects what researchers have started calling “ecological grief.” It’s a mourning that comes when we slow down enough to register the changes happening in the more-than-human world. As Ashlee Cunsolo, a Labrador-based expert on the subject, puts it, “Grief is incredibly painful, and it can be very isolating and debilitating, but it also has the potential to bring people together and inspire action. We only grieve what we love.”

This week the emotions running through the Fairy Creek blockaders and their allies are rising urgency and defiance. In the lead-up to the coming injunction decision, activists and members of the public are holding a vigil for Fairy Creek outside the legislative assembly and the provincial courthouse in Victoria. It follows a month of old-growth rallies around the province from Prince George to Premier John Horgan’s office. Yesterday, Green party MLA Adam Olsen continued his party’s support for old-growth protection in the B.C. legislature, challenging the premier to provide conservation funding to Pacheedaht First Nation and to buy back the Fairy Creek cutblocks from Teal-Jones.

The Fairy Creek Blockade has raised more than $125,000 on GoFundMe, about $50,000 of that flowing in since Teal-Jones filed for its injunction. Joshua Wright, the teenager still working behind the scenes from Washington, has called for a “Cedar Summer,” a play on California’s “Redwood Summer” of 1990, and a “new War in the Woods.”

As for Shawna Knight, she’s still driving her black pickup truck around Fairy Creek’s gravel roads, delivering supplies and forging connections. It’s been a long, rainy winter building alliances between workers, Pacheedaht members, and the blockade’s amorphous crew of supporters. “It’s all about building relationships based on respect. That’s the whole thing,” she says.

As Knight and the blockaders brace themselves for the injunction, the long game is coming to a head. “I think this is the climax, this is the moment we’ve all been waiting for,” she says. “We’re not going anywhere. We’re going to do what it takes.”

[Top photo: The blockade in the Fairy Creek watershed has faced criticisms for not receiving support from Pacheedaht First Nation, whose territory includes the watershed. Photo: Will O'Connell]