Articles Menu

10 December 2019

The climate crisis isn’t a future we must fight to avoid. It’s an already unfolding reality. It’s the intensification of extreme weather – cyclones, storms and floods, droughts and deadly heat waves. It’s burning forests in Australia, the Amazon, Indonesia, Siberia, Canada and California. It’s melting ice caps, receding glaciers and rising seas. It’s ecosystem devastation and crop failures. It’s the scarcity of resources spreading hunger and thirst. It’s lives and communities destroyed, and millions forced to flee.

This crisis is escalating at a terrifying rate. Every year, new temperature records are set. Every day, new disasters are reported. In Australia, we’re living through a summer of dust and fire. Hot winds from the desert are sweeping up dirt from the parched landscape and covering towns and cities hundreds and thousands of kilometres away. Creeks and riverbeds are being baked dry. Our cities are shrouded in smoke from fires burning for weeks on end, while on the hottest and windiest days the flames grow, devouring everything in their path.

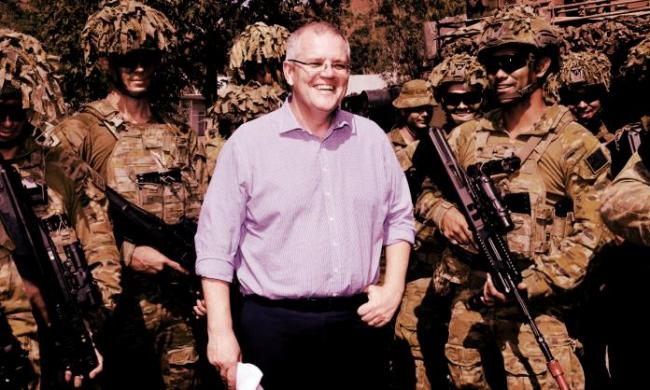

Do our rulers – the political leaders and corporate elites who, behind the facade of democracy, make all the important decisions about what happens in our society – understand the danger we face? On the surface they appear unconcerned. In September, after millions of school students participated in the global climate strike and Greta Thunberg gave her “How dare you!” speech at the United Nations, prime minister Scott Morrison responded by cautioning “against raising the anxieties of children”. And when, in November, hundreds of homes were destroyed and four people killed by bushfires in New South Wales and Queensland, he told the ABC there was “no evidence” that Australia’s emissions had any role in it and that “we’re doing our bit” to tackle climate change.

Is Morrison stupid? Somewhere along the line it appears his words have become unmoored from reality, and are now simply free-floating signifiers, spinning out of control in a void of unreason. As the empirical evidence of the devastation being caused by climate change in Australia and around the world mounts, so too does the gulf between this reality and the rhetoric of conservative coal-fondlers like Morrison grow into a seemingly unbridgeable chasm.

But something is wrong with this picture. To believe that someone in Morrison’s position could genuinely be ignorant of the dangers of climate change is itself to give up on reason. The prime minister of Australia is among the most well-briefed people on the planet, with thousands of staff at his beck and call to update him on the latest developments in climate science or any other field he may wish to get his head around. The only rational explanation is that Morrison and his like are aware of the dangers posed by climate change but are choosing to act as though they’re not.

On first appearances, this might seem like a fundamentally irrational standpoint. It would be more accurate, however, to describe it as evil. Morrison is smart enough to see that any genuine effort to tackle the climate crisis would involve a challenge to the system of free market capitalism that he has made his life’s mission to serve. And he has chosen to defend the system. Morrison and others among the global political and business elite have made a choice to build a future in which capitalism survives, even if it brings destruction on an unimaginable scale.

They are like angels of death, happy to watch the world burn, and millions burn with it, if they can preserve for themselves the heavenly realm of a system that has brought them untold riches. This is language that Morrison, an evangelical Christian, should understand. What might be harder for him to grasp is that he’s on the wrong side.

When seen from this perspective, everything becomes clearer. In the face of the climate crisis, the main priority of the global ruling class and its political servants is to batten down the hatches. Publicly, they’re telling school kids not to worry about the future. Behind the scenes, however – in the cabinet offices, boardrooms, mansions and military high commands – they’re hard at work, planning for a future in which they can maintain their power and privilege amid the chaos and destruction of the burning world around them.

**********

We’re not, as some in the environment movement argue, “all in this together”. There are many ways in which the wealthy minority at the top of society are already protected from the worst climate change impacts. Big corporations can afford to spend millions on mitigating climate change risks – ensuring their assets are protected so they can keep their business running even during a major disaster. Businesses and wealthy individuals can also protect themselves by taking out insurance policies that will pay out if their property is damaged in a flood, fire or other climate-related disaster.

The rich are also protected from climate change on a more day to day level. They tend to live in the leafiest suburbs, in large, climate-controlled houses. They have shorter commutes to work, where, again, they’re most often to be found in the most comfortable, air-conditioned buildings. They’re not the ones working on farms or construction sites, in factories or warehouses – struggling with the increasing frequency of summer heatwaves. They’re not the ones living in houses with no air conditioning, sweating their way through stifling summer nights. They have pools and manicured lawns and can afford their own large water tanks to keep their gardens green in the hot, dry summer months.

What about in the most extreme scenarios, where what we might call the “natural defences” enjoyed by the wealthy are bound to fail? What happens when the firestorms bear down on their country retreats or rising seas threaten their beach houses? Money, it turns out, goes a long way. In November 2018, for instance, when large areas of California were engulfed in flames, and more than 100 people burned to death, Kanye West and Kim Kardashian hired their own private firefighting crew to save their US$50 million Calabasas mansion.

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, the city’s wealthiest residents evacuated well in advance and hired a private army of security guards from companies such as Blackwater to protect their homes and possessions from the mass of poor, mainly Black residents who were left behind. Investigative journalist Jeremy Scahill went to the city in the aftermath of the hurricane and witnessed first-hand the highly militarised and racialised nature of the response. One security contractor, hired by a local businessman, told Scahill his team had been fired on by “Black gangbangers”, in response to which the contractors “unleashed a barrage of bullets in the general direction of the alleged shooters ... ‘After that, all I heard was moaning and screaming, and the shooting stopped. That was it. Enough said’”.

In the event of disaster, the response of the rich hasn’t been to work with others to ensure the collective security of all those affected. It has been to use all resources at their disposal to protect themselves and their property. And increasingly, as in New Orleans, this protection has come in the form of armed violence directed at those less well off – people whose desperation, they fear, could turn them into a threat.

The most forward thinking of the super-rich are aware that we’re heading toward a future of ecological and social break-down. And they’re keen to keep ahead of the curve by investing today in the things they’ll need to survive. Writing in the Guardian in 2018, media theorist and futurist Douglas Rushkoff related his experience of being paid half his annual salary to speak at “a super-deluxe private resort ... on the subject of ‘the future of technology’”. He was expecting a room full of investment bankers. When he arrived, however, he was introduced to “five super-wealthy guys ... from the upper echelon of the hedge fund world”. Rushkoff wrote:

“After a bit of small talk, I realized they had no interest in the information I had prepared about the future of technology. They had come with questions of their own ... Which region will be less affected by the coming climate crisis: New Zealand or Alaska? ... Finally, the CEO of a brokerage house explained that he had nearly completed building his own underground bunker system and asked: ‘How do I maintain authority over my security force after the Event?’

“The Event. That was their euphemism for the environmental collapse, social unrest, nuclear explosion, unstoppable virus, or Mr Robot hack that takes everything down ... They knew armed guards would be required to protect their compounds from the angry mobs. But how would they pay the guards once money was worthless? What would stop the guards from choosing their own leader? The billionaires considered using special combination locks on the food supply that only they knew. Or making guards wear disciplinary collars of some kind in return for survival.”

There’s a reason these conversations go on only behind closed doors. If your plan is to allow the world to spiral towards mass death and destruction while you retreat to a bunker in the south island of New Zealand or some other isolated area to live out your days in comfort, protected by armed guards whose loyalty you maintain by threat of death, you’re unlikely to win much in the way of public support. Better to keep the militarised bunker thing on the low-down and keep people thinking that “we’re all in this together” and if we just install solar panels, recycle more, ride to work and so on we’ll somehow turn it all around and march arm in arm towards a happy and sustainable future.

The rich don’t have to depend only on themselves. Their most powerful, and well-armed, protector is the capitalist state, which they can rely on to advance their interests even when those may conflict with the imperative to preserve some semblance of civilisation. This is where people like Morrison come in. They’re the ones who have been delegated the task, as Karl Marx put it in the Communist Manifesto, of “managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie”. In the context of climate change, this means taking the steps necessary to ensure the continued ability of the capitalist class to profit even if the world may be unravelling into ecological breakdown and social chaos.

There are three main ways in which Australia and other world powers are working toward this. First, they’re building their military might – spending billions of dollars on ensuring they have the best means of destruction at their disposal to help project their power in an increasingly unstable world. Second, they’re building walls and brutal detention regimes to make sure borders can be crossed only by those deemed necessary to the requirements of profit making. Third, they’re enhancing their repressive apparatus by passing anti-protest laws and expanding and granting new powers to the police and security agencies to help crush dissent at home.

Military strategists have been awake to the implications of climate change for a long time. As early as 2003, in a report commissioned by the Pentagon, US researchers Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall argued that “violence and disruption stemming from the stresses created by abrupt changes in the climate pose a different type of threat to national security than we are accustomed to today. Military confrontation may be triggered by a desperate need for natural resources such as energy, food, and water rather than conflicts over ideology, religion, or national honor. The shifting motivation for confrontation would alter which countries are most vulnerable and the existing warning signs of security threats”.

More recently, a 2015 US Department of Defense memorandum to Congress argued: “Climate change is an urgent and growing threat to our national security, contributing to increased natural disasters, refugee flows, and conflicts over basic resources such as food and water. These impacts are already occurring, and the scope, scale and intensity of these impacts are projected to increase over time”.

The Australian military has also been preparing for an increasingly unstable geopolitical environment driven in part by the impact of climate change. The 2009 Defence White Paper included a section, “New Security Concerns: Climate Change and Resource Scarcity”, which pointed to the vulnerabilities of many countries in our region. The paper was explicit in linking these to a possible increase in “threats inimical to our interests” and suggested that military capabilities would need to be strengthened accordingly. A 2018 Senate inquiry into the implications of climate change for “national security” drew similar conclusions.

Although discussions about military preparedness are often pitched in terms of the need for increased development assistance, disaster relief and so on, the practice of the US, Australian and other military powers over the past few decades leaves little room for doubt as to what their role will be. When they’re not invading countries on the other side of the world – killing hundreds of thousands, reducing cities to rubble and imprisoning and torturing anyone who opposes them – to secure access to fossil fuels, they’re acting as the enforcers of capitalist interests closer to home.

The response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 is again a good example. When troops from the US National Guard joined the army of private contractors sent to establish “security” amid the death and destruction of the hurricane’s aftermath, the Army Times described their role as quashing “the insurgency in the city”. The paper quoted brigadier general Gary Jones as saying, “This place is going to look like Little Somalia. We’re going to go out and take this city back. This will be a combat operation to get this city under control”. A similar dynamic was at work in Australia when, in 2007, the Howard government sent troops to establish “order” in remote Indigenous communities as part of the racist Northern Territory Intervention.

The idea that the military could be a force for good in the context of environmental catastrophe and social breakdown is laughable. Whatever the rhetoric, the role of the military is to secure the interests of a nation’s capitalist class amid the competitive global scramble for resources and markets. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman had it right when he argued in 1999: “The hidden hand of the market will never work without a hidden fist – McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the US Air Force F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley’s technologies to flourish is called the US Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps”. The military are gangsters for capitalism. And in the future, they’re likely to double down on savagery.

The next way in which the world’s most powerful capitalist states are preparing for climate catastrophe is by massively increasing what’s euphemistically called “border security”. In 2019, Germany celebrated 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, an event supposedly ushering in a new age of freedom and democracy. In the decades since, however, European countries have built around 1,000 kilometres of new border walls and fences – six times the length of that hated symbol of totalitarianism in Berlin. Most have been constructed since 2015, when millions of Syrians were forced to flee and seek sanctuary in Europe amid a brutal civil war that was triggered in part, at least, by climate change.

A 2018 report by the World Bank, Groundswell – Preparing for Internal Climate Migration, found that just three regions (Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South-East Asia) could generate 143 million climate migrants by 2050. Australia’s immediate neighbourhood will be affected severely, with several Pacific island nations forecast to disappear completely under rising seas. Already, in response to the relatively small numbers of refugees who have managed to reach Australia by boat in the past few decades, the Australian government has established one of the world’s most barbarous detention regimes. Other governments are now following suit.

So far, the measures discussed have been those primarily directed outwards by states seeking to defend the interests of their capitalist class in the international sphere. This is in part designed to create an “us and them” mentality within the domestic population. In Australia, this has been a staple of both Labor and Liberal governments for decades – the idea that the outside world is dangerous, full of terrorists and other bad people whom we should trust the government to protect us from. In the context of growing global instability associated with climate change, we can expect governments everywhere to double down on these xenophobic scare campaigns.

This should be resisted at every step. Not only for the sake of those “others” – civilians in Afghanistan, refugees imprisoned on Manus Island and so on – whose lives the government is destroying in the name of our security. But also because the racist fear of the outsider promoted by our governments is designed in large part to draw our attention away from the increasingly direct and open war being waged against the “others” within.

In the years since the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, Western governments have expanded and strengthened the state’s repressive apparatus. Today we’re seeing, as many predicted, how the crackdown on basic freedoms carried out in the name of the “war on terror” has created a new normal in which anyone opposing the government’s agenda becomes a target. Environmental protesters, and anyone else standing up against the destructive neoliberal order, are now firmly in their sights.

In the US, the battle to halt the construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline provides the most extreme example to date. In November 2016, the Native American blockade at Standing Rock was broken up by a police operation so heavily militarised that it looked like something out of the invasion of Iraq. In sub-zero temperatures, blockaders were attacked with water cannons, tear gas, rubber bullets and concussion grenades. Hundreds were injured and many hospitalised. Two women who were involved in the blockade and who later vandalised the pipeline are now facing charges under which they could be jailed for up to 110 years.

In Australia, we’ve seen those protesting peacefully outside the International Resources and Mining Conference in Melbourne face an unusual level of police violence and mass arrests. In Queensland, the state Labor government has passed new laws targeting environmental activists. In early December, three members of Extinction Rebellion were jailed when a magistrate refused them bail – something without precedent for charges related to acts of non-violent civil disobedience.

**********

Perhaps nothing provides a better metaphor for the future our leaders are steering us towards than a picture, taken during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, of the New York city skyline shrouded in the darkness of a blackout – all except one building, which remained lit up like a Christmas tree. That building was the headquarters of global banking giant Goldman Sachs, where, protected by a mountain of sandbags and using a back-up generator, the company was able to keep the lights on and the profits flowing even while the city was inundated by a three-metre storm surge and hospitals, schools, the subway and most other services were forced to close.

If you imagine this picture as the world, and the Goldman Sachs building as the gilded realm inhabited by the world’s super-rich and the political class that serve them, all you’d need to add is some heavily armed guards around the building and you’d get a pretty good sense of what’s ahead. Our rulers’ apparent lack of concern about climate change is a ruse. They hope that, if they can just head off dissent for long enough, they will succeed in building this future, brick by brutal brick, and there will be nothing the rest of us can do about it.

We need to fight for something different: a system in which our economy isn’t just a destructive machine grinding up human and natural resources to create mega-profits for the rich. One in which the productive life of society is managed collectively by those who do all the work, and where decisions are made not in the interests of private profit, but in the interests of human need. We need socialism – and the fight for it is the great challenge of our generation. At stake is nothing less than the world itself.