Articles Menu

May 16, 2022

Prabhat Patnaik’s recent books include A Theory of Imperialism (Columbia University Press, 2016) and Capital and Imperialism: Theory, History and the Present (Monthly Review Press, 2021), both co-written with Utsa Patnaik. This article was published in Peoples Democracy on May 15, 2022.

For over two years now, the world has been facing a pandemic the like of which has not been seen for a century, and which has already taken 15 million lives according to the WHO, without being anywhere near an end. This is an unprecedented crisis for humanity as a whole, which requires a massive effort on the part of every government, especially governments in third world countries where the people are particularly vulnerable not just to the disease but also to the destitution it brings in its train.

They have to expand hospital facilities, keep adequate numbers of hospital beds ready, create testing facilities, make vaccines available and set up vaccination facilities, and so on. In addition, the governments have to provide relief to the people through transfers, and succor to small producers who are likely to go under. All this requires an increase in expenditure on the part of governments.

But precisely because of the pandemic, production suffers and with it the government’s revenue at existing tax rates. Unless they raise wealth tax rates, they have to enlarge their fiscal deficits, therefore, as a proportion of GDP. They have in short to adopt policies that run directly contrary to the dictates of neo-liberalism, that violate all constraints imposed by so-called “fiscal responsibility” and that abandon all concern with fiscal “austerity.”

But let us see what has actually happened.

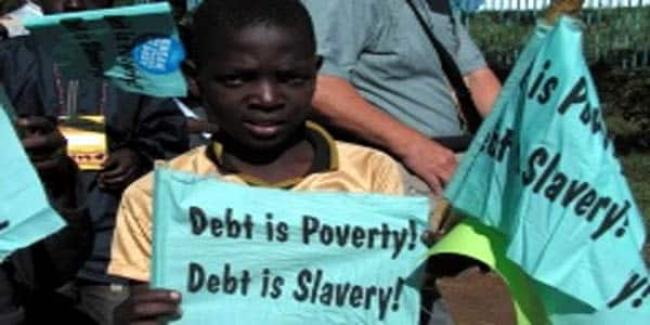

Precisely because of the slowing down or stagnation of the world economy, exports of third world countries suffer. To be sure, so do their imports because of the slowing down of their own GDP growth rates; but even assuming that exports and imports are affected to the same extent so that the trade deficit or surplus moves down in tandem with the GDP, the fact remains that inherited external debt commitments have to be met whose magnitude relative to GDP must increase. These debts need to be rolled over and their servicing has to be suitably deferred. In other words, even if the trade flows relative to the GDP remain the same for all countries after the pandemic as before, while the GDP itself stagnates, the external debt stocks rise relative to GDP because of this stagnation.

The debt burden, therefore, becomes greater and requires special accommodation to be offered to third world countries.

The most obvious way that this can be done is to have a debt moratorium for a certain number of years; and within contemporary world capitalism, the institution that has to be entrusted with implementing such a debt moratorium is the IMF, which should also be encouraging countries to abandon “austerity” and spend on people’s health and welfare during the crisis. In fact, the current managing director of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, has often told some member countries to abandon “austerity” in this time of crisis, from which one may get the impression that the IMF has at last seen the magnitude of the threat to mankind as a whole posed by the pandemic. For instance, she urged Europe recently not to “endanger its economic recovery with the suffocating force of austerity.”

But the reality, it turns out, has been quite different.

Oxfam has recently analyzed 15 loan agreements signed by the IMF with third world countries in the second year of the pandemic, and 13 of these explicitly insist on “austerity.” Such “austerity” measures include taxes on food and fuel and spending cuts by governments that would inevitably affect basic services like education and healthcare. In the case of six additional countries with which negotiations have been going on, the IMF is also insisting on similar measures being adopted by them.

This insistence on “austerity” cannot be dismissed as an exception. Earlier on October 12, 2020, Oxfam had reported that since March 2020 when the pandemic was declared, the IMF had negotiated 91 loans with 81 countries; and of these in as many as 76, namely in 84 per cent of loan agreements, there was an insistence on “austerity” which would not only make life harder for the poor people caught in the grip of the pandemic but also result in a squeeze on healthcare expenditure. The IMF’s insistence on “austerity” therefore continues as strongly as ever, even at a time when the people of the world can least bear its burden.

Not surprisingly, Oxfam has underscored the contrast between Kristalina Georgieva’s advice to Europe not to be constrained by “austerity,” and the actual program the institution she heads insists on for the third world, which is to observe “austerity.” On this basis, Oxfam has accused the IMF of using “double standards,” one for the advanced countries and a different one for the third world countries. The use of double standards is abhorrent at all times; but its use at the time of a pandemic which is affecting mankind as a whole is particularly abhorrent.

What the Oxfam analysis misses however is the fact that the double standards evident in the IMF’s behavior, are immanent in the nature of capitalism itself. Indeed, a class society necessarily entails double standards: a laborer cannot march into a bank and apply for credit, but of course, a rich person can apply for and obtain credit. Put differently, the amount of capital one can get from “outside” sources depends on the amount of “own” capital one has, which is why ownership over capital is an essential condition for being a capitalist. If this were not the case then anybody could become a capitalist, so that there would be perfect social mobility rather than a hiatus amounting to class division.

In fact, intellectual defenders of capitalism like Joseph Schumpeter who attributed the origin of profit not to the ownership of the means of production but to the fact that those who became capitalists had a special talent, which he called innovativeness, actually asserted that anybody with such innovativeness, namely anybody with an idea that can be used to create a new production process or a new product, can obtain a loan from banks and set up a business.

But such attempts to obliterate class divisions in society are palpably false; no agricultural laborer, no matter how innovative an idea he or she may have, can set up a business (though of course the idea can be stolen by a rich man to start a business).

Exactly in the same manner, in a world of imperialism where countries are divided into two distinct categories — metropolitan and peripheral countries — metropolitan banks would be much more loath to give loans to peripheral countries than to metropolitan countries; there will necessarily be “double standards” in the matter of giving loans. The IMF, as the custodian of international finance capital that is dominated by metropolitan financial institutions, has to maintain these “double standards” in sanctioning loans and in imposing conditions for getting back the loans.

The Oxfam-type criticism of the “double standards” on the part of IMF, therefore, is based on the misconception that the IMF is a well-meaning humane institution that is supposed to look after the interests of mankind, rather than being a capitalist institution that is supposed to look after the interests of international finance capital.

The IMF’s behavior is thus reflective of the very nature of capitalism, of its essential inhumanity. I do not mean “inhumanity” merely in the sense that it places profits before people, but also in the sense which follows from it, namely that it does not see all human life as of equal value, that it necessarily applies “double standards” in every sphere of life. For instance, when the demand is raised that polluting industries should be shifted from the metropolis to the periphery, the obvious assumption behind this demand is that human life in the periphery is not worth as much as human life in the metropolis.

The invidiousness of a social system that is based on this fundamental discrimination, or “double standards” if you like, becomes evident especially in periods like now, in the midst of a pandemic. When both humanity and sagacity demand that we should be concerned with all human life, no matter where it is located, a social system that discriminates between them, that considers some lives to be of value, not others, stands out for its inhumanity and irrationality.