Articles Menu

Feb. 4, 2025

Last summer, when The Tyee learned about B.C.’s secretive plan to tighten its response to protests in the province, we had questions.

Nearly six months later — and only after filing and receiving a freedom of information request — we finally received an answer.

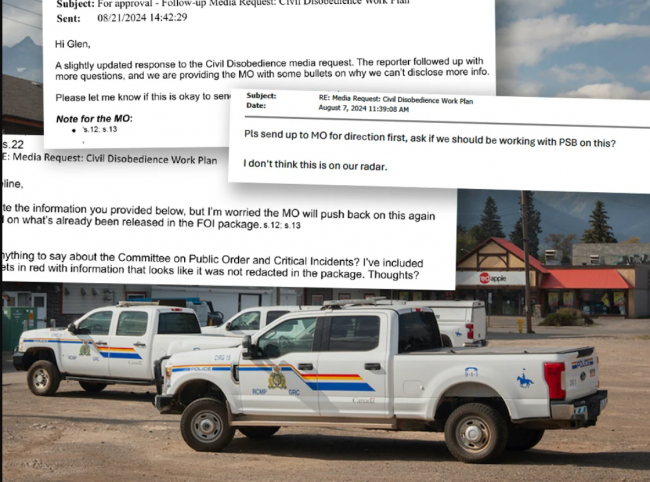

Dozens of internal emails The Tyee received in response to its FOI request provide a behind-the-scenes look at how a reporter’s questions quickly reached top officials and triggered a carefully strategized response from a communications team, only to be withheld from the public.

Sean Holman, the Wayne Crookes professor in environmental and climate journalism at the University of Victoria, said the province’s refusal to respond to media questions — which are asked on behalf of the public — smacks of creeping authoritarianism.

“There is a great concern these days about the erosion of democratic norms and the rise of authoritarianism,” Holman told The Tyee.

“This is how it happens,” he added. “If this government is concerned about the erosion of democratic norms worldwide and increases in authoritarianism, it should be trying to support democratic norms.”

But as a former government communications staffer, Holman said he’s seen it happen many times.

“We should be deeply concerned,” he said. “It’s not just a concern for journalists.”

The Tyee learned about the province’s plan, which was initially known as the Civil Disobedience Work Plan, through freedom of information legislation that provides access to internal government documents. Under B.C.’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, public bodies can withhold some information under certain exemptions.

The plan was launched in December 2021. That summer, old-growth logging protests on Vancouver Island had grown to become the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history. In November, police also carried out a high-profile enforcement, the third in several years, related to the Coastal GasLink pipeline conflict in Wet’suwet’en territory.

Weeks later, following direction from the premier’s office, B.C.’s Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General began a process to review how it responds to protests in the province. The initiative brought together various provincial ministries and police agencies to forge a “new model” for managing civil disobedience, according to internal briefing notes.

The Tyee emailed questions about the plan to the Public Safety Ministry in early August 2024. We published our initial story three weeks — and several followups — later, after the ministry did not provide a response.

In October, The Tyee made a freedom of information request for any internal communications about our media request to the Public Safety Ministry. The response, provided last month, contained more than 100 pages of emails discussing The Tyee’s questions and crafting a proposed reply.

The emails show that, within an hour of making the request on Aug. 7, The Tyee’s questions had made their way to the office of then-public safety minister Mike Farnworth, whose chief of staff at the time, Michael Snoddon, flagged the original FOI response to several communications staff.

“This is all PSSG and is based on an FOI that is attached,” Snoddon wrote. PSSG refers to the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General.

Two days later, an internal email hinted that a response might not be forthcoming.

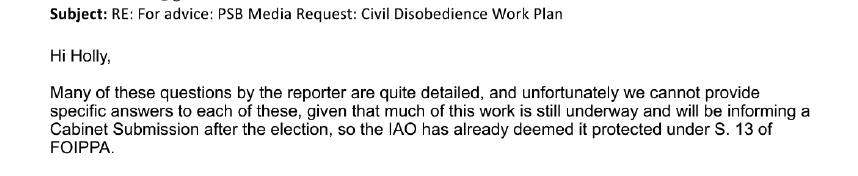

“Many of these questions by the reporter are quite detailed and unfortunately we cannot provide specific answers,” the sender, whose name was redacted from documents provided to The Tyee, wrote to a communications manager with the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General’s policing and security branch. The work was “still underway” and would be informing a cabinet submission after the election, the sender added.

The sender’s name was withheld under sections of B.C.’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act meant to protect law enforcement and personal privacy.

The sender then floated a proposed response containing about six bullet points. Much of its wording was taken directly from the initial FOI response that had sparked The Tyee’s questions in the first place.

“Protests across the province are multi-dimensional in all aspects, including motivation, location, scope and impact,” the proposed response read, adding that protests have become “an ongoing fixture of day-to-day life in B.C.”

“This has a disproportionate impact on police as it requires them to divert precious resources away from other public safety pressures,” it added. “Police leaders have repeatedly raised concerns about the financial impacts arising from responses to sustained protests.”

Work to develop options for a new model to manage public order led the ministry to form the Public Order and Critical Incidents Work Plan, an updated title for the Civil Disobedience Work Plan.

That work plan “outlines the strategic goals of the Public Order and Critical Incidents Unit,” the response continued. The process would explore different options to “monitor and manage” public order and critical incidents, it said.

About a third of the province’s proposed response was redacted from the recent FOI disclosure under sections of the act that protect cabinet confidences and policy advice.

Once it’s public, the decision ‘has already been made’

The government declined to comment on the internal email that said a submission related to the protest work plan would be put before cabinet, citing confidentiality.

Formal submissions to cabinet pave the way for legislative changes. If it were to be approved by cabinet, the submission would inform the drafting of a bill to be presented in the legislature. But cabinet discussions are kept confidential to allow decision-makers to “freely consider” their options, according to the province.

Holman described the process of deliberating in darkness “ridiculous” and unnecessary. Given the BC NDP’s current majority, any legislation put forward in the legislature is sure to pass. It means that B.C.’s “primary decision-making body” is operating in secrecy, he said.

“It’s a fait accompli by the time it makes it into the legislature,” Holman added. “The public isn’t actually being given an opportunity to comment and react. This is a decision that’s already been made.”

In its Aug. 7 query, The Tyee had also asked about the province’s Critical Incident Secretariat, a secretive arm of the Public Safety Ministry’s policing and security branch that had a hand in guiding the process to create a new model for managing civil disobedience.

The province’s proposed response said that the Critical Incident Secretariat was established in 2017 and meets on a biweekly basis, “bringing together cross-government partners in the natural resources and energy extraction fields, to provide situational awareness across government regarding public order and critical incidents pertaining to the natural resource sector.”

The Critical Incident Secretariat does not have a “public-facing website,” the ministry said, because it is “internal to government and deals with highly sensitive information.”

In other documents provided to The Tyee through FOI, the name of the person hired to lead the Critical Incident Secretariat was redacted under sections of the act that protect law enforcement and personal privacy.

When the province launched its plans for a new approach to civil disobedience, its first task was to “enhance” the Critical Incident Secretariat’s role within the ministry, according to internal documents. That began with renewing the contract with the person leading the secretariat “for at least another term.”

A flurry of emails

In the week following The Tyee’s Aug. 7 request to the Public Safety Ministry, staff continued to tweak their response. On Aug. 15, there was a flurry of emails as the team prepared to sign off and send the bullet points to B.C.’s public relations branch.

“Alert [the deputy minister’s office] to this one please,” wrote Public Safety Ministry assistant deputy minister Glen Lewis.

In the hours that followed, the minister’s office, including its chief of staff, Snoddon, continued to offer suggestions. Snoddon’s comments are entirely redacted under a section of the act that protects policy advice and recommendations.

But the discussion indicates the feedback wasn’t positive.

“I appreciate the information you provided below, but I’m worried the [minister’s office] will push back on this again just based on what’s already been released in the FOI package,” a communications manager wrote. “I’ve included some bullets in red with information that looks like it was not redacted in the [FOI] package. Thoughts?”

On Aug. 21, as The Tyee prepared to publish our story, we sent additional questions to the Public Safety Ministry. The internal discussions that followed indicated that staff believed a response had already been sent — and that no more information was likely to be provided.

“The response we provided earlier still stands. Unfortunately, we cannot provide any additional info — including in response to the followup questions,” a communications manager wrote.

It’s unclear where the draft response went from there. On Aug. 28, The Tyee published the story without comment from the Public Safety Ministry.

When we asked about the response two months later, in October, the ministry said the request would need to be resubmitted following the post-election interregnum period.

Where’s the plan now?

The Tyee reached out again to the Public Safety Ministry last week, asking about the lapsed response. This time, the ministry responded, explaining that “due to the complexity of the issues, we were not able to get you an approved response to your original request at the time.”

“We are currently engaging with policing partners in advancing key components of the workplan,” the ministry said.

“Ongoing external collaboration with partner ministries is being facilitated to establish an integrated approach.”

The ministry also provided the long-awaited response to The Tyee’s original questions. Its comments closely mirrored those drafted in August and shared previously in this story.

The spokesperson said the ministry could not provide details about plans to provide a work plan submission to cabinet given the confidential nature of the process.

Anything related to specific outcomes expected for the work plan has been redacted from the documents provided to The Tyee.

Amanda Follett Hosgood is The Tyee’s northern B.C. reporter. She lives in Wet’suwet’en territory. Find her on Bluesky @amandafollett.bsky.social.

[Top photo: An FOI request made by The Tyee uncovered more than 100 pages of emails discussing a response to our media request about BC’s secretive plan to tighten protest response. Government emails obtained via FOI. Photo by Amanda Follett Hosgood.]