Articles Menu

Katzie Nation Chief Susan Miller and her sister Debbie Miller of Katzie First Nation say they stand to lose everything if the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline expansion is approved.

Chief Miller said the continued expansion of pipeline projects and shrinking of Indigenous territories represents the ongoing assault on First Nations culture that started with the residential school system.

"I think that if you want to look at it from the very cold, hard fact of squishing us in, that genocide continues," she said darkly. "We have the opportunity to stop that genocide, should the government finally recognize Aboriginal rights and title."

Chief Miller was accompanying her sister, who spoke at the National Energy Board hearings on Kinder Morgan's Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project at the Delta Hotel in Burnaby. If approved, the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain expansion would add brand new pipeline to an existing system that already carries 300,000 barrels per day of crude oil and refined petroleum from the oil sands in Alberta to refineries on the west coast.

The proposal would triple the pipeline's capacity, adding new tanks and pump stations across the province. The expansion would also increase tanker traffic in Burrard Inlet nearly seven-fold.

"We’re right in the heartland of that last vintage of rural community, and with the water, because we’re in the tidal zone still, if there should be a natural or manmade disaster, that area is going to be highly affected. It’s the route that the salmon come through," she explained.

"We have the ability to work together and prosper. We should be partners in every single development that happens in B.C. It is on somebody’s Indigenous land. It’s all unceded, we’ve never given up our rights to it."

The Katzie territory is vast and beautiful, the sisters explained. It encompasses both urban and rural land, stretching from the southern B.C. cities of Surrey, Langley, Whiterock, Coquitlam, and Port Coquitlam, to the diverse ecosystems of the Pitt and Alouette watersheds.

The Fraser River, called "the most important natural artery in British Columbia" by Canadian Geographic Education, runs directly through it, and 80 per cent of the territory is located on provincial parks.

"The Fraser River is literally our front door," said Chief Miller. "When you get up in the morning all you see is water. It’s beautiful, it’s quiet — we’ve got deer and bear and ducks and geese and lovely fish."

Her eyes lit up when she talked about the berry-picking, hunting, shoot-harvesting, and salmon fishing that takes place there all year round. The Katzie band has roughly 550 members, many of whom still have traditional lifestyles on one of the nation's five reserves.

"It’s gorgeous," added Debbie Miller. "Katzie in our Halkomelem language… is ‘the land that the moss was turned over,’ so literally, the places where we live are the places our ancestors told us to turn the moss over and create homes for ourselves."

This heritage, this ancestral territory, this lifestyle — all of this is what the Katzie First Nation has to lose if the Trans Mountain expansion is approved, they said.

Sunset over the Fraser River. Photo by James Wheeler on Flickr Creative Commons, Off the Beaten Path.

Sunset over the Fraser River. Photo by James Wheeler on Flickr Creative Commons, Off the Beaten Path.

According to Trans Mountain, pipeline safety is a "number one priority" in all of its projects, past, present and future. This includes spill prevention, seismic safety measures, emergency preparedness, marine response — "a mature suite of programs to maximize the safety of the pipeline."

What its expansion proposal does not consider however, said Debbie, is the safety of the communities, Indigenous people, and ecosystems its construction would impact.

"Many people talk about what it means to be safe, and I can only tell you from us as a people that our systems and our life ways are integral to ensure our identity is maintained," she told NEB panelists during the hearing early Wednesday morning.

"It’s my responsibility and the people’s responsibility to continue to teach those systems and activities to the young people and those who have yet to come."

Kinder Morgan has recognized that pipeline expansion project would effect riparian areas and destroy wetlands, both of which are vital to the Katzie First Nation's way of life.

With such high stakes on the table, said Debbie, the concept of 'safety' should include not only the physical security of people and environments, but their livelihoods as well. In the case of the Katzie, she argued, the pipeline expansion would displace them by compromising the rich natural resources they use for survival, and therefore threaten the traditions of their ancestors.

"For us, there isn’t another place to go," she explained. "Our territory has brackish and fresh water marshlands, and it is two these marshlands that we go to gather resources when they are needed. They are gathered for purposes that I cannot explain to you in 40 minutes."

No one is off to a very good start, she added, given that she — as the chief of the Katzie First Nation — was not permitted in the NEB hearing room.

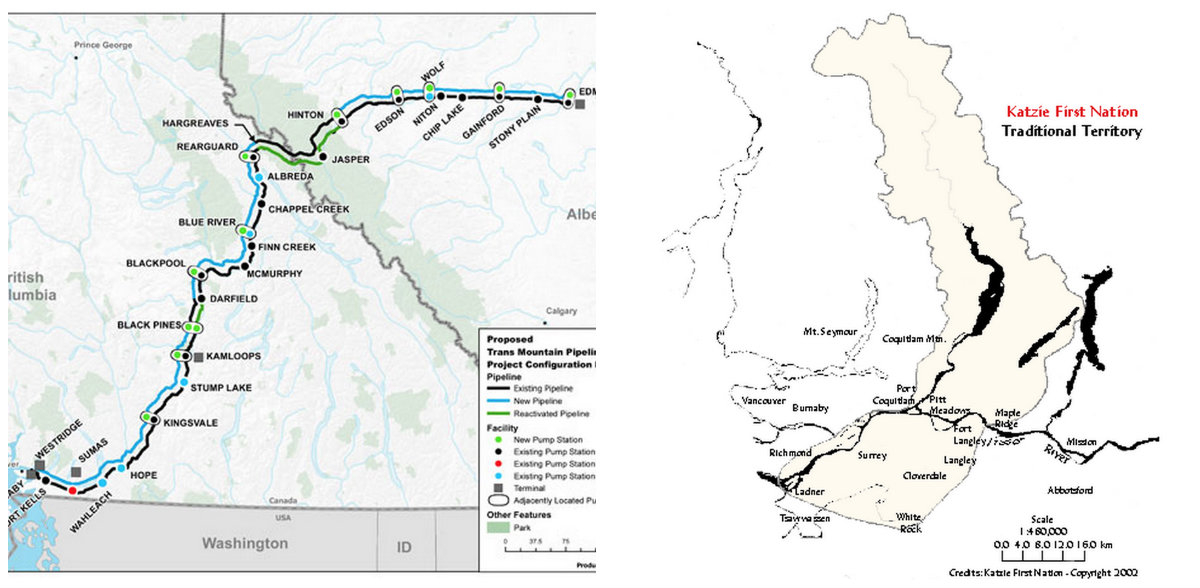

A map of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project (left) next to a map of the Katzie First Nation's traditional territory. Graphics by the National Energy Board and Katzie First Nation.

A map of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project (left) next to a map of the Katzie First Nation's traditional territory. Graphics by the National Energy Board and Katzie First Nation.

According to NEB regulations, only interveners and their 'plus ones' may be present in the hearing room during the proceedings. For the band, it had to be Debbie, the chief treaty negotiator and its lawyer, Jennifer Griffith. Chief Susan Miller would have been a third representative, and wasn't allowed to enter even if she didn't speak.

Under normal circumstances, Katzie traditions would have the chief introduce Debbie as the nation's spokesperson, and introduce the nation as a whole by explaining their connections to the land, who their fathers and grandfathers were, and the cultural values of their ancestors.

In a hearing process designed without the input of Indigenous leaders however, there is "little place for Aboriginal people," said Debbie, who already had to deviate from her Coastal Salish cultural "rules" by reading her arguments off a piece of paper rather than sitting down with the panelists and offering oral testimony, eye-to-eye with them.

"If one looks at the colonial construct of the actual room itself — the actual divides between us and the people who are there to listen to us — in our way, we would be gathered in a circle," she explained, reunited with her sister in the lobby of the hotel in Burnaby where the NEB hearings took place.

Susan agreed and said that the practice of reading arguments off a paper inherently disadvantages Indigenous interveners:

"We speak to people and we talk from our heart. You can gauge your audience by their reaction so you have an opportunity to speak to their hearts. This process doesn’t allow that."

Susan spent the morning of the hearing in the lobby, eagerly awaiting news of how the presentation went. She and her sister were warmly greeted by a small group of protesters, who waved anti-Kinder Morgan signs determinedly outside the building.

"One of the reasons I chose to be here today was to be able to make that statement," she said defiantly. "Even though I wasn’t allowed in the room where they’re speaking, I’m here."

The NEB hearings on the Kinder Morgan expansion project will continue in Burnaby until Jan. 29, and include testimony from more than 15 First Nations from Canada and the United States.