Articles Menu

Dec. 8. 2020

The Ministry of the Future is a timely literary provocation and one of the most important books of the year in any genreSeveral years ago, our family went to a holiday season performance at a kids’ art space in downtown Vancouver. The venue was also hosting an exhibit about children’s visions of the city 100 years from then. Most of the illustrations were dystopian scenes from an early 22nd-century future. The sea level rises anticipated under worst-case climate scenarios were depicted through submerged skyscrapers and washed-out roads; eco-apartheid was implied in crayon, with colourful but unmistakably unwelcoming border walls to keep out the teeming masses of Californian climate refugees.

That exhibit made me think that the line attributed to Fredric Jameson — about it being easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism — was in fact an understatement. Our children can’t even imagine a future above water.

In this miserable year of the pandemic, the end of the world feels like it’s here already. In these circumstances, it takes a heroic act of imagination to conjure up a medium-term scenario in which humanity grapples with the existential threat that ecological degradation and climate disruption poses to our societies, our species, and indeed the biosphere itself.

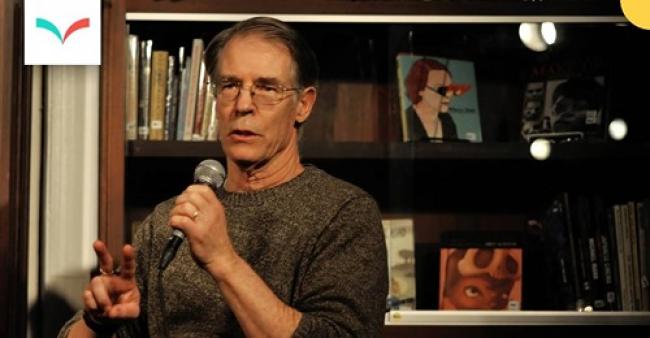

Enter Kim Stanley Robinson, the veteran science fiction author famous for his Mars trilogy. The Ministry of The Future (Orbit, 2020) might be his most ambitious standalone novel to date, and it’s one of the most important books in any genre to appear this year.

The Ministry is a daring, provocative history of the next 30 years. Against the grain of late capitalist dystopian imagination, Robinson, better known by his initials, KSR, has produced a sprawling, grimly realistic yet stunningly optimistic story of how the world might avert the worst of the climate catastrophe.

The titular ministry is a deceptively staid UN-affiliated outfit based in Zurich and headed by a middle-aged Irish diplomat, Mary Murphy. Its mission is to see that the historic promises made in the Paris climate agreement are actually implemented. Anchored in seemingly non-revolutionary bureaucratic halls, and set amid downright non-futuristic mountaineering episodes in the Alps, the novel manages to achieve a hyperrealist mood even while relentlessly breaking every limit imposed by polite society and our current political moment.

No environmental NGO would dare hint at some of the tactics that prove decisive in turning the tide in The Ministry. Propaganda of the deed is imagined on a scale never before seen, as a shadowy international guerilla-type organization carries out targeted assassinations on fossil fuel executives, and even takes the global elites gathering at Davos hostage for a few days, turning the World Economic Forum into a sort of re-education camp for capitalists.

Robinson has described The Ministry’s format as docudrama, and this allows for rapid-fire recaps of episodes like the one at Davos, as well as a number of short chapters that serve as polemical interludes on the nature of economics and money, among other topics. The withering critique of mainstream economics reaches its crescendo when Murphy leads the charge to encourage the world’s big central banks to introduce Carbon Quantitative Easing and a “carbon coin” — put simply, creating money to be spent first on efforts related to achieving decarbonization.

Although the notion of commandeering finance to solve the ecological crisis is perhaps the biggest single idea deployed, there is no silver bullet in The Ministry, no magic carbon sequestering technology that will save us on its own. In this tale, a combination of strategies and policies by state and non-state actors, including mass uprisings, geoengineering, and Green New Deals weave together to create conditions by mid-century to at least give humanity a fighting chance at long-term survival.

The future history in The Ministry is so epic that not even 563 pages can do it justice. Momentous events such as a Yellow Vest–inspired new French revolution, and a similarly transformative movement in the U.S. sparked by a coordinated student debt strike, are mere rough sketches on this canvas. The focus on India as a decisive global political actor is refreshing, and this is perhaps the most prescient aspect of the book. After the several-century interregnum of European imperialism and its declining U.S. progeny, global economic and political power is shifting back east.

While a deadly heat wave in India triggers the creation of the UN ministry, the northern bureaucrats by no means call all the shots. KSR’s gritty but hopeful future is a decidedly post-colonial one, in which both state and non-state actors act independently and in morally ambiguous or problematic ways to confront the climate emergency by any means necessary. Even in this imaginary realistic-but-best-case scenario, the next 30 years include violence, displacement and conflict on a vast scale. The Ministry provides hope, but with no illusions.

Several years ago, acclaimed author Amitav Ghosh, in his book The Great Derangement, excoriated the literary, or “serious,” novel for its failure to grapple with the immense issues posed by the climate crisis. Although one could read the polemic by Ghosh, one of the world’s finest historical novelists, as in part self-criticism, he had precious little to say about speculative fiction of any kind. Ghosh’s critique was valid but incomplete. More needed to be said about the imperative to get beyond myopic definitions of serious fiction. Who gets to decide what is or is not literary fiction?

As we come out of the pandemic facing the great climate challenge, it’s hard to imagine a more serious novel than Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry of the Future.