Articles Menu

We saw the delegates hugging each other as they walked out of the COP21 climate change talks in Paris back in December — but we had no idea what the agreement they reached meant for Canada.

Now we do. And it turns out Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall was quite right to be anxious about the future of our fossil fuel industry and Alberta Premier Rachel Notley may have been quite wrong in her assertion that Alberta will prosper — if she was talking about the oil and gas industry, at any rate.

The 2015 International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook forecasts $7.4 trillion in global investment in renewables by 2040, as well as a push to boost energy efficiency. It also sees GDP growth in developed and developing countries decoupling somewhat from fossil fuel consumption. That moves us off the path of a 4°C temperature increase that featured in previous outlooks.

But the IEA forecast still sees a temperature rise of 2.7°C by the end of the century in the absence of any stabilization efforts. This temperature rise, they argue, would be driven by a continuing reliance on fossil fuels; in the 2014 to 2040 timeframe they see coal use up 10 per cent, oil up 12 per cent and natural gas up 47 per cent. Under this scenario, Canada’s oil production grows from four million barrels per day in 2014 to seven million by 2050.

Premier Notley can rightly say that Alberta would prosper under this scenario, with production increasing and the real price of crude rising to draw out more high-cost supply.

But this is not what was agreed to in Paris.

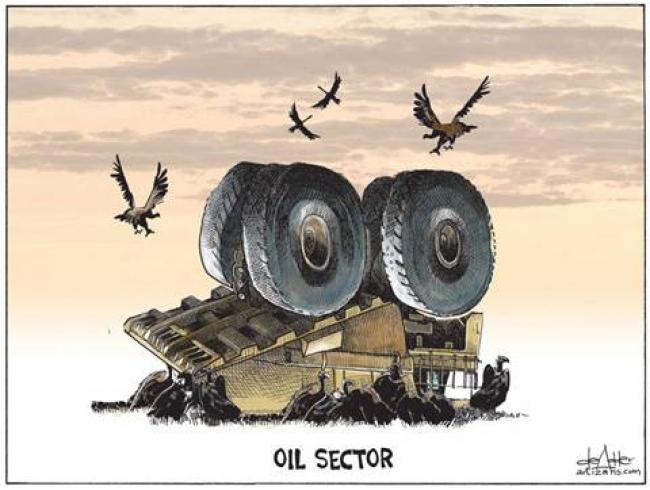

We must accept that, if the world succeeds in getting out of the carbon economy, much of Canada’s energy sector will have to be dismantled.

We must accept that, if the world succeeds in getting out of the carbon economy, much of Canada’s energy sector will have to be dismantled.

The IEA also looked at a scenario that would see the temperature increase limited instead to 2°C by the end of the century. This scenario would see a larger, faster shift to renewables and efficiencies driven by more aggressive carbon pricing. Globally, coal would see a 28 per cent drop by 2030 and oil would sees a 6 per cent decline, but natural gas would see an increase of 20 per cent.

In a world of declining oil and coal use, Alberta’s oilsands cannot prosper, given the high carbon content of bitumen (in terms of carbon content, every barrel of bitumen is like a combination of lighter crude oil and coal). Any future growth in oilsands output under this scenario is highly unlikely — although natural gas may have a future.

But remember — Paris aspired to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5°C, not 2°C. The 1.5° scenario was explored in a recent article in the scientific journal Nature Climate Change. It concludes that, under a 1.5° target, we can only burn about half the carbon we can consume under the 2°C scenario before carbon neutrality must occur.

By 2050, carbon emissions in the transportation sector could be forced to drop by 70 per cent from 2010 levels, while residential and commercial sector emissions could drop by 95 per cent. In the electrical generation sector, carbon emissions could go to zero and then even lower, through biomass use and carbon sequestering. We’d probably have to stop burning coal well before 2050 and allow for only limited natural gas use for electricity generation and home heating. Oil use could drop dramatically, due to decreases in transportation sector emissions.

So if the world moves to limit the increase in temperature to 2°C, then the oilsands sector probably cannot grow, although natural gas may have some use. If the world moves to 1.5°C, then the oilsands sector has no future at all — and even Canada’s natural gas production is questionable on a long term basis.

What should the premiers be talking about? As far as national targets go, it makes sense to look at Canada’s economy in two baskets: oil and gas, and everything else.

The provinces need to position those parts of their economies that are outside the oil and gas sector for the future, by pushing green electrification and carbon pricing to drive the necessary changes in the most efficient manner.

The oil and gas sector contributes 25 per cent of our national greenhouse gas emissions. The future of this sector will be determined by the success or failure of the rest of the world’s efforts to decarbonize. We must accept that, if the world succeeds in getting out of the carbon economy, much of Canada’s energy sector will have to be dismantled.

So the consequences for Canada of the Paris accord come down to two inescapable truths: We need to plan for the future of sectors other than oil and gas — while for the oil and gas sector itself, there may not be a future.

Ross Belot is a retired Canadian energy industry manager who has been working in global energy markets for decades with a focus on supply and economics. He is a published author, photographer, documentary short filmmaker and is currently enrolled in the MFA program at St. Mary’s College of California.