Articles Menu

Dec. 4, 2024

In the days after Donald Trump’s election, business leaders across a swath of industries celebrated the victory of a man they thought would bring them a financial bonanza. Crypto bros, oil and gas honchos, and tycoons looking to orchestrate mergers all did a victory dance.

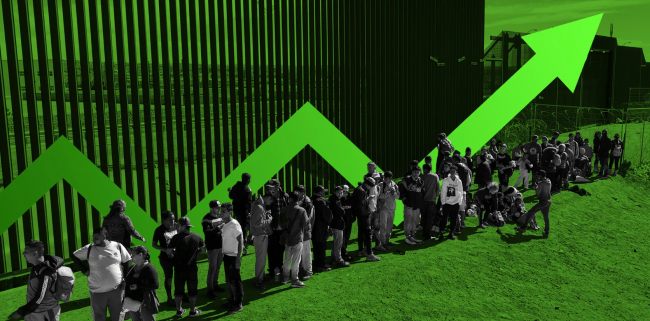

Now, a new report details how private equity companies — operating in relative obscurity — stand to benefit too. Trump’s promised mass deportation campaign will enrich private equity companies, according to a new report released Wednesday by a watchdog organization tracing the industry’s far-reaching involvement in the business of detention and deportation.

“Declaring an emergency opens up all these avenues for companies to rush in without the proper vetting.”

“Trump is pretty set on expanding the deportation and detention system, he is pretty set on declaring a national emergency, and as shown in the report, declaring an emergency opens up all these avenues for companies to rush in without the proper vetting,” said Azani Creeks, the senior research and campaign coordinator at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project. “The companies with the most power and the most money will win those contracts — so that will be private equity firms.”

For years, advocates concerned about private industry’s role in immigration have focused their ire at two large, publicly traded companies that dominate the business of owning and operating lock-ups for immigrants.

Those companies, Geo Group and CoreCivic, both saw their stocks soar after Trump’s election on the expectation that he will follow through on his pledge to deport millions of people.

While private prison operators might play top dog at many detention facilities, advocates say they are only one part of a constellation of companies that stand to profit off deportation. Some companies are simply privately held, but a growing number are owned by private equity firms.

Those firms do not offer stock to the general public, instead collecting investments from pension funds and other institutional funders to buy companies they believe are undervalued. Sometimes they make structural changes and sell their acquisition targets for a profit. Sometimes, they slash expenses by firing employees and use the companies they have purchased as piggy banks by issuing debt in their name.

Unlike publicly traded companies, which must disclose certain financial information, there is little visibility into the world of private equity.

Creeks said that while some publicly traded companies pull back from operating in the detention and deportation world under public pressure, private equity firms have rushed in to fill the void. Some 63 percent of federally designated immigration detention facilities contract with companies owned by private equity firms, according to the report.

Asked for comment by The Intercept, none of the firms listed in the report that are mentioned in this story provided one.

The services that the private equity-owned companies provide might sound like a benefit at first blush: Immigration detainees obviously need access to nurses and doctors, for instance. Still, Creeks said inserting a profit motive into services such as health care carries serious risks for immigrants.

“Private equity’s main purpose is to generate high returns for investors,” Creeks said. “We see declining services. So in the example of health care, companies across the country are facing labor shortages. This of course is very dire for folks who are incarcerated, and we see really really poor medical service.”

One of the top private equity-owned medical providers, Wellpath, operates at 12 detention facilities in states ranging from California to Florida, according to the report. The company, which also provides services to people in criminal detention, has been named in more than 1,000 lawsuits, including 70 alleging wrongful death.

Wellpath’s owner, H.I.G. Capital, owns another company called TKC Holdings that served a detention facility in Laredo where immigrants complained of “inedible food and undrinkable, foul-smelling water,” according to the report.

Even the telephone calls that immigrants in detention make to their loved ones serve as a profit center. Two private equity firms, American Securities and Platinum Equity, dominate the jail and prison telecommunications industry through firms they own.

In July, the Federal Communications Commission cracked down on prison phone companies by capping how much they can charge for calls. Republican state attorneys general are challenging the phone rate caps in court. Regardless of how that case plays out, the report says that companies such as ViaPath and Securus have found new ways to profit by offering tablets where detainees can pay to access entertainment.

A security firm called G4S ultimately owned by the private equity firm Warburg Pincus has racked up contracts with Customs and Border Protection and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement amounting to more than $1 billion for transportation and security services that include deportation, according to the report.

Another private equity owned firm, Peraton, has a contract with DHS estimated at $6.2 billion to develop a massive biometric database.

Private equity firms are also heavily involved in artificial intelligence — which could be employed to aid in deportation efforts under the second Trump administration, according to Creeks.

The rising number of private equity-owned contractors serving ICE, the Department of Homeland Security, and other federal agencies involved in detention and deportation mirrors private equity’s growing influence in the U.S. economy writ large.

The number of companies owned by private equity firms has soared over the past two decades, eclipsing the number of companies that are publicly traded around 2012. More and more employees ultimately answer to private equity firms promising sky-high rates of return to their investors.

Those investors in many cases are pension funds representing government employees or other big institutional investors. Though the lack of transparency obscures details about the actions of private equity firms from the public, former teachers and firefighters may have a stake in their operations regardless.

“We’re all implicated in it, in a way,” Creeks said. “Given that these are services that are run by federal and state and local governments, I think there should be greater measures of transparency and accountability for those companies that we just don’t have access to, because of the private equity structure.”

[Top: Photo illustration: The Intercept / Photo: Lokman Vural Elibol/Anadolu via Getty Images]