Articles Menu

June 16, 2021

While the year 2020 saw numerous activist mobilizations, it was the police murder of George Floyd that instantly filled streets around the world with outraged protest. People marched, torched police stations, tore down statues, and confronted police in actions noticeable both for their dedicated persistence and the diversity of participants. There is no question this uprising was effective in certain ways; a much-needed spotlight has been focused on racialized, militarized policing, on the lack of accountability within police unions, and on the basic injustice of the carceral state in general.

And yet. Given the level of outrage, it must be acknowledged that little change has occurred at the policy, much less the institutional level. Commissions are formed, local reforms proposed, and a predictable backlash invigorated, replicating a long-established pattern of protest followed by bureaucratic inertia. Time and again we witness the absorption of movement energy into the grinding processes of the regulatory labyrinth.

As with gun control following school shootings, with climate action following extreme weather events, with antiwar protests in anticipation of invasions, with international trade deals, with Occupy or pipeline blockades, the pattern is clear. I am not saying that protest is dead. My argument is that these particular forms of reactive protest are no longer effective.

What I would like the Climate Movement to consider is a tactic that moves beyond protest as it is now conceived and practiced. This nonviolent, direct action tactic is best described as “fill the jails.”

While the mass civil disobedience of both anti-KXL in Washington DC in 2011 and Extinction Rebellion more recently were steps in the right direction, the historical examples of mass arrest I am promoting have a qualitative difference.

I first learned of “fill the jails” when researching the free-speech fights conducted at the beginning of the 20th century by the Industrial Workers of the World. From San Diego, California to Missoula, Montana, Wobblies defied local ordinances that banned impromptu public speaking. They gained the right to openly organize by calling in masses of fellow workers to be arrested and fill jails until the burden on local authorities became overwhelming. Another historical example is Gandhi’s India campaign, where he vowed to “fill the prisons” in order to make governing impossible for the British.

Perhaps the best-known example of this tactic being applied successfully is the Civil Rights Movement, especially the campaign centered in Birmingham, Alabama (the “most segregated city in America”), in 1963. This is how the large-scale, non-violent direct action was described by historian Howard Zinn:

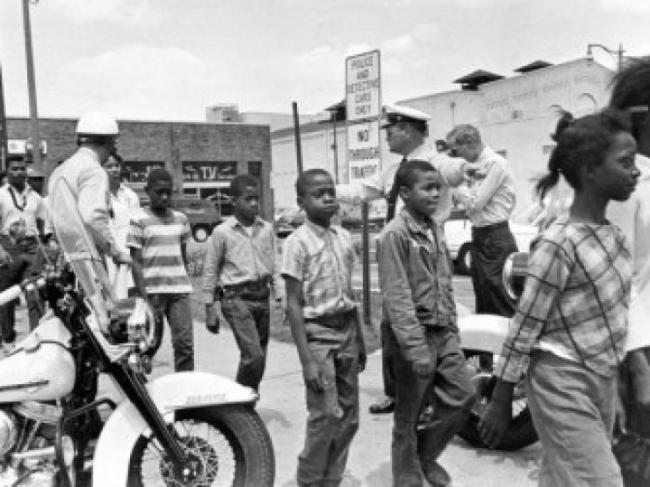

“Thursday, May 2nd, is ‘D-Day’ as students ‘ditch’ class to march for justice. In disciplined groups of 50, children singing freedom songs march out of 16th Street Baptist church two-by-two. When each group is arrested, another takes its place. There are not enough cops to contain them, and police reinforcements are hurriedly summoned. By the end of the day almost 1,000 kids have been jailed. The next day, Friday May 3rd, a thousand more students cut class to assemble at 16th Street church. With the jails already filled to capacity, and the number of marchers growing, Eugene ‘Bull’ Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety in charge of the police and fire departments, tries to suppress the movement with violence.”

Between April 3 and May 7 roughly three thousand were arrested and booked, filling not only the jails but an “improvised fairground prison … and open-air stockade” as well. This all took place in conjunction with a well-organized boycott of downtown businesses and public transport. Televised scenes of savage reaction by the racist police were broadcast throughout the stunned world and a horrified nation — which was then forced to confront the injustice.

That was then.

Compare this with the more recent “George Floyd Uprising.” In 1963 Birmingham there was an established leadership and structure for coordinating strategy and tactics. The movement had well-trained, highly disciplined cadres willing to face enormous risks including barbarity and prison time. It was precisely this well designed, concerted effort that created an untenable situation for the power structure. In the recent uprising, and the BLM protests more generally, there are large, undisciplined, untrained actors spontaneously pursuing an uncoordinated “diversity of tactics” that include everything from peaceful marching to arson to property destruction. There is little or no leadership able to direct actors or even form coherent messaging. At the end of each day the protestors go home, and by and large the power structure remains unchallenged.

I am not singling out just BLM; this style of protest has been prevalent since Seattle and alt-globalization struggles, where large forces converged using a wide array of tactics and purposefully avoiding any centralized structure. This applies to what Naomi Klein dubbed “Blockadia” as well. Throughout the decades-long fight against fossil fuel infrastructure, countless people have been jailed, but always in scattered, isolated, small contingents. From Tim DeChristopher to Standing Rock to the “valve turners,” these one-off, individual actions have held moral and symbolic meaning for the movement but have not resulted in escalation to anywhere near the scale required.

A long-standing example of this “affinity group” approach is the annual gathering at Fort Benning, Georgia to protest what was known as the School of the Americas (it has since changed its name). Every year since 1990 thousands, at times tens of thousands, gather while a handful (the largest contingent was 40) of protesters risk arrest. We need to ask: What might have happened had all 20,000 risked arrest?

Tactics do not equal strategy.

The dynamic between social justice organizations and the quasi-anarchist black blocs is a case study in mutual tactical failure. If your theory of change equates power with media spectacle, you might believe smashing windows, spray painting walls, or starting fires is effective and that no one has the right to limit your participation in any given situation. My argument here is that this theory fails on every point, that while civil rights strategists in Birmingham used the media to effectively present their message, the black bloc/anarcho/antifa tactics of today do the opposite.

To be clear, I am not making a moral claim one way or the other about property damage or use of force. In his book How To Blow Up a Pipeline, author Andreas Malm suggests two rules: (1) “nonviolent mass mobilization should (where possible) be the first resort, militant action the last; and (2) no movement should voluntarily suspend the former, only give it appendages.”

This “radical flank” approach makes sense to me; if “filling the jails” proves ineffective, there is no question in my mind that sabotage, vandalism, and the like are entirely justified in defense of the biosphere. I simply believe that before resorting to those tactics, it is time for “protest” to relinquish the folk politics of horizontalist, esoteric “diversity of tactics” and adopt a new/old model of disciplined direct action that embraces organized structure. Autonomous, consensus-based affinity groups, each doing their own thing, have demonstrably failed to “get the goods” — as have the millions of peaceable, permitted marchers with their banners, puppets, and drums (not to knock the value of spectacle in capturing some imaginations).

Positive change begins with self-evaluation and reassessment. We begin by acknowledging that fetishizing decentralization and diversity of tactics has been largely unsuccessful. Too often protest becomes a personal spiritual quest where “each person must do what he or she thinks is right.”

Following the tragic events in Genoa, Italy, where Carlo Giuliani, a protester against the G8, was killed by police, the political scientist and activist Susan George quoted the great Chinese strategist Sun Tzu:

“Do not do what you would most like to do. Do what your adversary would least like you to do.”

That was 2011, and the lesson still has not been learned. Today’s protests, demonstrations, and direct actions have become repetitive, boring, scripted affairs and have generally failed to build the energized, militant force required to confront our planet’s converging, cascading crises.

Therefore, movement strategists will need to rethink all these sclerotic, contemporary forms: the one-off mass mobilization/rally with its predictable signs, speeches, chants … and outcome; the isolated, dispersed acts of nonviolent civil disobedience; the street-fighting with police or right-wing groups; and certainly the random, wholesale property destruction that the mass media and its advertisers so love.

It is my hope that organizers will look to these historical accounts of highly trained, thoroughly disciplined, but otherwise ordinary workers, students, and other caring people peacefully yet militantly facing down the most brutal, violent regimes of state oppression.

Consider the consequences African Americans in 1960s Birmingham faced. The risks they were willing to take. And what they achieved.

[Top photo: More than 1,000 children were arrested marching for justice on "D-Day," May 2, 1963. Photo courtesy of the Zinn Education Project]