Articles Menu

Sept. 12, 2024

The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.”

—Karl Marx, The German Ideology

There is an ideological tendency among some liberal economists today that wants us to believe that Bidenomics has been the best thing since President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. A key advocate of this belief is economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman. On September 7th, 2023, Krugman published an article titled “I’m OK, But Things Are Terrible” in which he claimed there is a disconnect between actual economic conditions and perceptions about the economy: “[t]he strange thing is that these bad ratings are persisting even as the economy, by any normal measure, has been doing extremely well.” Krugman and others who are fans of Bidenomics find it odd that when workers are asked about “the economy” their views are generally negative. This issue is especially relevant now that Harris and Walz are at the top of the ticket for the Democratic Party, as their economic policy proposals so far appear to be a watered-down Bidenomics 2.0.

On the positive side of the ledger, it is true that the official unemployment rate is the lowest it has been for decades—based on August 2024 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the current rate is 4.2%. It has been low for a considerable amount of time, and this is not something to dismiss, although there are now some signs of weakness. Biden and Congress have spent a considerable amount of money to “reshore good manufacturing jobs.” To that end, “we’ve created close to 800,000 manufacturing jobs since I’ve taken office,” Biden said late last year on X, a claim that PolitiFact rated as “mostly true.” It is also worth mentioning that the U.S. economy has been performing much better than its peers.

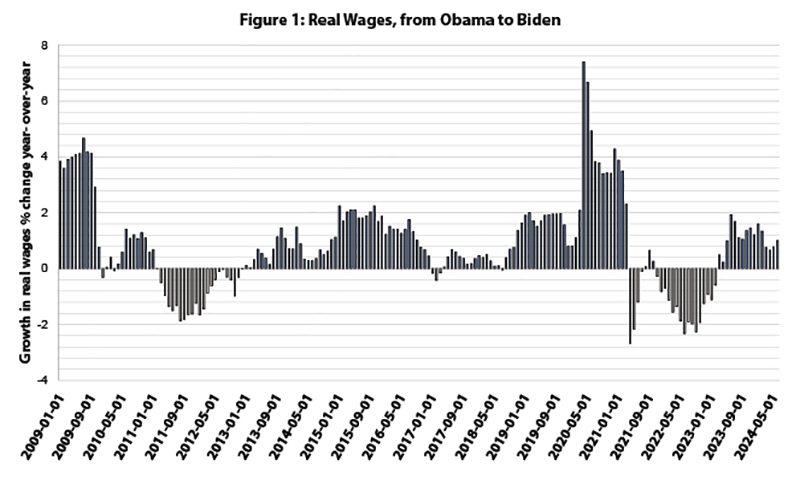

In addition to low unemployment, Krugman’s case rests on real wage growth. (“Real wages” are wages and salaries adjusted for changes in overall prices.) We know that inflation decreased significantly starting in the spring of 2023, according to the Consumer Price Index. Furthermore, nominal wage growth for production and nonsupervisory workers has started to outpace inflation, so that real wages have risen since March 2023 (see Figure 1). So, even though real wages were falling during a portion of the first half of Biden’s term, real wages are now rising at about 1% per year.

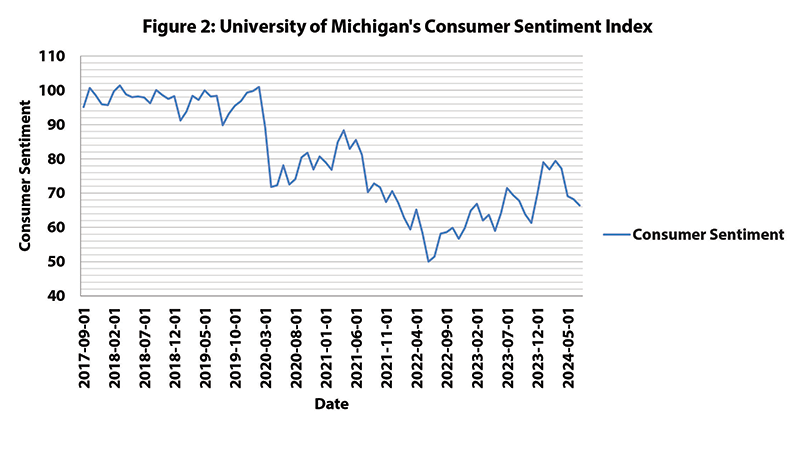

Despite an apparently good economy, in terms of unemployment and real wages, Krugman claims that sentiments have not fully incorporated this rosy picture. Krugman’s assessment is corroborated by different sources. The Consumer Confidence Index compiled by the University of Michigan indicates that confidence remains below pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 2). As the chart shows, while there has been some recovery since mid-2022, the massive dip in consumer sentiment following the pandemic is very clear and continues to affect voters’ view of the economy.

Another critical source of information about economic perceptions is the General Social Survey (GSS), which is primarily used by sociologists, and has been collecting data about U.S. society since 1972. The GSS is a nationally representative survey about various opinions, attitudes, and behaviors. Topics covered include civil liberties, morality, economics, and more. Importantly, it is the best single source for attitudinal trend data in the country.

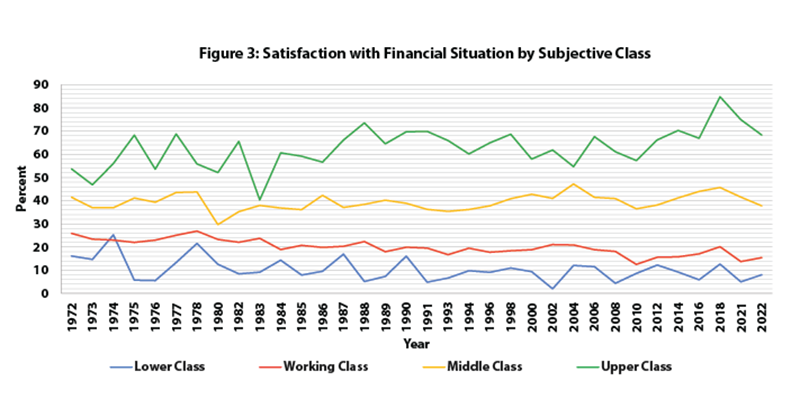

What does the GSS have to say about perceptions of the economy and financial well-being? Consider, first, the overall financial situation of most Americans. What percentage are satisfied with their financial situation, and are there any trends that stand out over time? Looking at the data, we note that since the early 1970s about 30% of those surveyed are satisfied with their financial situation and this percentage has been fairly stable for the last 52 years.

It is, however, more informative to consider financial satisfaction when broken down by “subjective class identification.” Respondents are asked to select which of four social classes they belong to, and the four options are: lower class, working class, middle class, and upper class. (It is worth pointing out that if we were to use more objective measures of class identification, like occupation, income, or wealth, we would possibly see different results.) Nevertheless, the stratification remains striking if we consider subjective identification. Only those who consider themselves “upper class” report being satisfied with their financial situation, and in relative terms, members of the working class and middle class report considerable dissatisfaction. This has been the case for decades (see Figure 3).

What can explain this contradiction between what economists like Krugman consider to be good economic indicators and the perspective of everyday people? What economists such as Krugman like to stress is that the media has not done its job of reporting the good news. In 2022, Krugman said on CNN, “I think that what’s happening now is that there’s been a kind of a negativity bias in coverage,” pointing to a “media failing” when it comes to accurately covering the realities of what most Americans are experiencing in this economy. Even Dean Baker, an economist to Krugman’s left, published an article in The Nation this summer berating the media for failing to report accurate information on the state of the economy. But Baker, and other economists making a similar point, neglect to consider the GSS data, which clearly indicates that workers have been unhappy with their personal finances since the start of the neoliberal era.

This contradiction did not emerge just because of negativity bias in the media. Different classes—ranging from the lower and working classes to the middle and upper classes—have widely varying perceptions of their financial situation. What Krugman fails to understand is that there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all perception of the economy—because different classes have different economic experiences. Clearly, the working and lower classes are generally unhappy with their financial situation (and that has been true for decades, not just under Biden), whereas the upper class, or what Marx called “the bourgeoisie,” is relatively content with their lot. How could it be otherwise in a capitalist society?

Contrary to what some economists think, we are living in what we could call the GoFundMe Economy. According to Bankrate.com’s Annual Emergency Savings report, 59% of adults are uncomfortable with their level of emergency savings, and this number has been increasing over time. Greg McBride, Chief Financial Analyst for Bankrate, noted that “[e]mergency savings has long been the Achilles heel of Americans’ personal finances. More households have no emergency savings and millions of households are far short of the savings they would need to feel comfortable.” Twenty-seven percent of adults have no emergency savings; only 44% could pay for an emergency expense of $1,000 or more, the report stated. This might be a medical emergency, perhaps to pay for a visit to the local emergency room; it might be money needed to cover an unexpected car repair. The uncertainty of whether it will be possible to pay for these kinds of expenses is a source of considerable economic anxiety for the working class and is rightly reflected in stratified perceptions about the economy.

Examples of the GoFundMe Economy are in abundance from the Appalachians to the Rockies. In our local tenant union in Kansas City, Mo., many requests come across on a regular basis with people asking for funds to finance emergency expenses. Uber drivers with car problems who don’t have enough money for repairs, thus putting their livelihood at risk. People who can’t pay the rent who then reach out to their networks of friends and family for financial support. To cite a specific example, a fundraiser on GoFundMe raised $3,000 for the union’s mutual aid account and the money was gone in a week. When raising money to cover emergency expenses via GoFundMe fails, the logical next step is becoming trapped in a cycle of debt. Economic anxiety is real, it is not merely the result of media bias, and should not be trivialized.

In addition, people’s perceptions of their financial situation are influenced by inequality. It is an open secret that income inequality in the United States has reached obscene levels not seen since the conclusion of World War II. Although there is no one-to-one correspondence between perceptions and economic inequality, the latter is an important structural variable and one that influences perceptions.

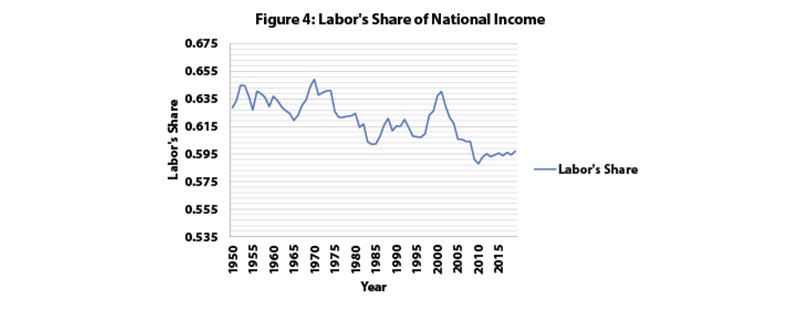

Two measures of economic inequality are especially noteworthy. Firstly, consider labor’s share of national income (see Figure 4). This variable has traditionally been a key measure of inequality for Marxist economists. What we see when examining this variable is that it has been trending downward for the entire post-World War II period, with a notable decline since 2002. Indeed, labor’s share of national income reached historical lows during the Great Recession of 2008 and has remained relatively low since. This suggests that regardless of economic growth, labor is getting a smaller and smaller piece of the economic pie. This empirical fact is entirely consistent with other measures of income inequality. Second, consider the percentage increase in the real income of the bourgeoisie compared to the bottom 50% of wage earners. According to research by economists Thomas Blanchet, Emmanual Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, over the period January 1976 to March 2023, the real income of the top 1% has increased 288% or about $1.4 million per household. By comparison, the real income of the bottom 50% has increased only 18.8% or a measly $2,900. Despite a relatively low unemployment rate, these are not characteristics of a healthy economy, and these structural realities have been incorporated into stratified worker perceptions.

The structural issues of U.S. capitalism are not confined to “the economy” alone—they are manifest across society. In Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Anne Case and Angus Deaton pointed out that certain demographics in the United States have experienced declining life expectancy. As Yves Smith of the finance blog Naked Capitalism noted back in 2015, “[o]ne of the long-standing patterns in economies showing economic growth is longer life spans, and falls are seen as the result of severe distress and dislocation, as took place in the period right after the fall of the Soviet Union, when the [life] expectancies of adult men fell by over seven years.” The United States has now replicated this dismal outcome. Case and Deaton report that from 1999 to 2013, the death rate among non-Hispanic whites aged 45 to 54 with a high school education or less, increased, while it fell in other age and ethnic groups. As a baseline, recall that the AIDS epidemic killed an estimated 700,000 from the mid-1980s to the present. In comparison, nearly half-million died in half that time period who would have lived if their mortality rates had fallen in line with the rest of the population. Again, this is not a characteristic of a healthy society.

So, what do we make of this supposed contradiction between people’s perceptions and the economic progress lauded under the Biden Administration?

It should be clear at this point that people continue to express widespread dissatisfaction with their financial situation, and this dissatisfaction has a real material basis in the structural realities of U.S. capitalism. Unlike what ruling-class economists such as Krugman would have us believe, this phenomenon dates back to at least the 1970s.

It is neither a media fabrication, nor a result of media bias. Working-class life under capitalism is an extraordinarily difficult affair—it’s a GoFundMe Economy. People are living paycheck to paycheck with very little money under the mattress, as we used to say, and workers are forced to make hard choices. It is true that real wages have increased and unemployment remains low. But these two empirical facts present an incomplete picture of the conditions of the working class in the United States. If Krugman’s argument is the best case that can be made for capitalism, then the argument is indeed quite weak. When we consider structural issues like income inequality and health outcomes, we see that something is very wrong in the Land of the Free. The parties of capital and their enablers expect us to be happy with the scraps they are offering. And they are surprised when we are not. It is not that hard to understand why workers appear to be unhappy with the economy. It is also not that hard to understand that the mainstream economics profession is a mouthpiece of the bourgeoisie.

Taki Manolakos is an economist and community organizer. He lives in Kansas City, Mo.

Dollars & Sense is a non-profit, non-hierarchical, collectively-run organization that publishes economic news and analysis, with the mission of explaining essential economic concepts by placing them in their real-world context. We publish a bi-monthly magazine, as well as economics books that are used in college social science courses, study groups and other educational settings.

Founded in 1974, Dollars & Sense is a publication of Economic Affairs Bureau, Inc., a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization. From its beginning, the Economics Affairs Bureau has been a worker-run, collectively managed organization. This organizational structure fits with the mission to challenge orthodox economics, to promote progressive economics, and to help build a movement for a new economic system.