Articles Menu

July 19, 2024

Here on The Tyee, University of British Columbia professor of landscape architecture Patrick Condon has often argued that merely rezoning for density and fast-tracking mainly market-rate developments won’t fix affordability crises in cities like Vancouver. His opposition to some developments and policies for not delivering enough low-income housing has drawn attacks from people who argue the time for such quibbling is past and we need the sweeping, denser zoning imposed from above by the BC NDP government.

Condon’s response over the past two years has been to go largely quiet in these pages while writing Broken City: Land Speculation, Inequality, and Urban Crisis, the academic, peer-reviewed book published this spring by UBC Press. Its basic thesis is that unfettered speculation, fuelled by global wealth looking for asset investments, drives Vancouver land costs up so high they erase savings that can be delivered by building many units on a parcel instead of a few.

That’s why, Condon says, new towers keep rising but their units cost pretty much the same as surrounding housing rather than pressuring price drops. If we don’t get a handle on land price super-inflation, he argues, we can’t deliver affordability. And he has some ideas about how to do that.

Settle in for a conversation that runs longish in service of the respectful probing for clarity and nuance needed in this charged moment for housing policy discussions.

David Beers: Hi Patrick, congratulations on Broken City. Truly a useful and provocative challenge to what a lot of us take for granted about housing affordability these days. I suggest we have a back and forth by email to craft an interview-like result. So, first question: Why did you write this book?

Patrick Condon: I wrote this book, originally, in a state of emotional cold fury. I was and am furious about how all the efforts made by me and others over the course of three decades of adding well-planned new density to this city failed to make housing affordable as we had hoped.

You see, what brought me to Vancouver originally was its reputation for “city building done right.” The urban life opportunities created at False Creek South and Yaletown were already famous in the 1990s when I arrived — famous for providing new medium- and high-density housing, with rich amenities at your doorstep, for average wage earners and their families.

I enthusiastically embraced the idea that if you got the density right, and got the amenities right, the home prices would be affordable as a result. That strategy became known as “Vancouverism” and is the visible legacy of hundreds of citizens, staff members and elected officials working to what was, in retrospect, a shared vision of a sustainable 21st-century city.

But as time passed and home prices spiralled more and more out of reach for average wage earners in defiance of simple notions of “supply and demand,” I felt betrayed. I know others my age and background in this city who feel the same sense of loss.

It’s not widely known but Vancouver has added more housing than any other centre city in North America. Since the 1970s, Vancouver has tripled its total number of housing units. If adding housing supply and new density to a city leads to affordable housing as many now contend, Vancouver should have the lowest housing prices in North America. It has the highest!

So this book is my attempt to understand why this didn’t work out, and what can be done about it.

Beers: And the thesis of your book is that land prices in Vancouver, which is a rather geographically confined global city, are unhooked from local income levels. Rather, at a moment when wealth is increasingly concentrated among a global elite, land has become the place to stash their wealth, and as they turn land into wealth-storing assets, they bid each other up. So that land prices now have increased fivefold in Vancouver over the past 15 years, while income levels have stayed fairly flat.

Still, people will say, no matter how expensive land gets, building 25 storeys of units on top of it instead of a single-family home is bound to yield more homes at more affordable prices. No?

Condon: You are correct that the common expectation is that this problem is solved if you just add new density onto expensive land in the hope of diluting the land price component. But if you just rezone for more density, you find that the main beneficiary of the upzoning is not the renter or owner, but the land speculator. And that the final rental or ownership cost of the new units is no lower, and most often even higher, than the housing units nearby.

That’s not true just for Vancouver; it’s global. Particularly throughout the so-called English-speaking world. Sydney, Australia, just edges out Vancouver on the very top of the Demographia list of the world’s most unaffordable cities when measured against median household income, which are the lowest of any North American centre city by the way.

Simply stated, urban land has the tendency to absorb every nickel of value created by the people living and working above it into its price.

Urban land is a monopoly product and like any monopoly there is little limit on its asset value, a price based on its location in the centre of commerce. “Buy land, they are not making any more of it,” Mark Twain famously said.

Twain said this at a time when it was more obvious to all, the height of the American Gilded Age when the fabulously wealthy were making most of their money on urbanized or urbanizing land. That historically repeating cycle of urban land wealth was interrupted in the early 20th century when sequential economic shocks — the First World War, the Great Depression and the Second World War — in relatively short order collapsed the relative value of urban land worldwide. So we got used to the idea of urban land price not being a serious impediment to affordable housing.

We are now in the habit of thinking if housing prices are too high it must be a problem of restrictive zoning, or construction costs, or taxes. It’s not. It’s a problem of our gradual return to the norm where land absorbs too much value uselessly, and unrelentingly, into the value of urban land. It’s the return of “landlordism,” really, a problem that the first real economist, Adam Smith, identified 250 years ago.

Beers: What you’ve just said would seem to be not at all “anti-progressive.” Instead, you seem to be naming ever widening wealth inequality and late capitalism as the culprit.

Yet I’ve noted when you’ve floated similar ideas when writing in The Tyee, you attract on social media all kinds of name-calling. People who say more and denser development is inherently a solution, and a progressive one, call you a NIMBY and all kinds of other names. It feels weirdly visceral to me, as if these “abundant housing” advocates don’t want to entertain your basic thesis.

And yet I have known you for 30 years and I know you to be squarely in the camp of those trying to make housing more affordable. You’ve never argued for keeping things the same. You’re no defender of single-family zoning. For example, you’ve argued in The Tyee for sweeping zoning that would lock in far more co-ops. You’ve argued market mortgage and rental developments should include more sub-market or not be built. You’ve argued for lots of forms of infill that have very much a densifying effect.

Why do you think you’ve received such backlash?

Condon: I am exactly identifying wealth inequality and late capitalism as the culprit. Or more precisely, a global economy that has moved markedly away from one based on earned wages to one based primarily on the value of assets — a global economy based on your assets making money, not your wages. Urban land now represents, by far, the largest single asset category on Earth, exceeding other categories by many trillions of dollars.

The housing problem, both here and elsewhere, is part of a larger global shift (as economist Thomas Piketty points out) from an economy based on wages to an economy based on assets. Currently the world’s growth comes from assets making money rather than wage earners making money. Of these assets, the lion’s share is in the single category of urban land, worldwide.

So, anyway, this shift has pushed the values of urban land up and out of sync with regional wages. Housing prices end up escaping their traditionally assumed “real estate fundamental” ratio of four to one, home price to annual wages. That ratio in Vancouver is now 12 to one.

My assertion is this: the only way regions can get control of this out-of-control phenomenon is by exerting control over the land base, and asking for a degree of social benefit to accrue from these global investments. This puts me in a different camp from those who argue that more market-driven density alone will bring down the cost of housing by itself. Sometimes, yes, I have spoken against denser development but not because I’m opposed to density, per se, but because if it can’t deliver affordability, then we must ask whether this particular proposed building is a good precedent to approve.

As for attacks on social media, I must say that the ability to block is a wonderful thing. But beyond that, it’s true that this turn of events is a peculiar twist for me to experience at the end of my professional career, after decades of writing and working with communities on making mixed-use, affordable and walkable communities come to life.

I guess to anyone that calls me a NIMBY I’d have to politely respond that this is laughable. And in this I am not alone. There are scores of now aging architects, planners, urban designers and elected officials who helped create this amazing city, who are similarly reviled for arguing, as I do, that just throwing proper planning away, with all its associated social benefits, the benefits that made Vancouverism famous, is not a path to affordability. The opposite is true. The ordinary tools of planning and zoning policy can and have been used to gain amazing levels of social benefits in this remarkable city.

To throw all of that away in blind allegiance to the libertarian conceit that an unfettered market will eventually lead to affordability is simply not credible. And it’s certainly not “progressive.” This attitude really represents a “trickle-down housing” revival of 1980s “trickle-down economics.” Trickle-down housing is no more likely to work now than did the trickle-down economics of the 1980s.

Beers: Yes, there has been, to me, a surprisingly sharp turn in popular notions of how to design a livable city, what was hailed in the late 20th century as the New Urbanism. As an adherent, you championed mixed-use, walkable, mixed-income neighbourhoods with three-to-six-storey buildings along a broad web of light rail lines as a way to densify a city while maintaining its human scale and reducing dependence on polluting cars.

There was also the feeling in your cohort that local citizens could be involved democratically in shifting their neighbourhoods towards such approaches, if the benefits were explained in a respectful way. Granted, in the richest parts of Vancouver the blowback to pretty much any changes has long been fierce. But residents in poorer neighbourhoods also enjoyed the right to speak out against what was planned for their communities.

Now local democracy has been swept aside by provincial fiat in ways that deprive all neighbourhood residents of much if any input.

What would you say to people who greet this change by saying the old approach gave residents too much power to protect single-family lots, and anything new, particularly lower-income housing, was nigh impossible to push through? Do we need to sacrifice local democracy for that reason?

Condon: That’s a contention that is wildly at variance with reality. First off, the complaint that housing is unaffordable because NIMBYs block new development is demonstrably false. For example, the previous council, charged with adjudicating all zone change requests in the context of public hearings, had 250 zone change requests that came before them. Despite many citizens raising objections at public hearings, all but one were approved, and that single instance was ultimately approved after design variations. So, if NIMBYs are the problem, they are a profoundly ineffective one.

Second, a lot of research shows that planning decisions do not restrict housing growth. At best they direct the market into mutually beneficial locations, enhanced by the negotiated public benefits consequent to the urban plan.

For example, Yaletown is a very well-planned area where market value was enhanced by amenity demands made on development, where proceeds from “land lift” ended up being used for things like the seawall, which in turn increased the value of nearby homes. A true “both and” solution. I am a strong believer that working with communities is the best way to arrive at these kinds of “both and” solutions. Former Vancouver city planning manager Larry Beasley often says the same thing.

Exemplary high-density projects like the Arbutus Lands result from this deep civic collaboration. My own work and publications draw from the strain of planning belief, manifested especially in my East Clayton project and described in my Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities book.

So, to blame local democracy for our affordability problems is a tragic mistake, especially here where highly collaborative, neighbourhood-focused urban design became world famous. We have sadly lost that plot.

The Broadway plan is based on the flawed notion that development need not pay for itself in the form of civic amenities and affordable housing because this will impede the magic of the “free market.” Vancouver is the built proof that this is false.

Beers: I’d like to return to an assertion you made quickly earlier in our conversation, one you elaborate on well in your book. You say:

“Simply stated, urban land has the tendency to absorb every nickel of value created by the people living and working above it into its price.”

Can you explain in a bit more detail how this works?

Condon: I first heard that phrase from Richard Wozny, a well-known Vancouver real estate consultant, now deceased. For me it took time to fully understand the significance of his aphorism.

It is this: when the public improves a part of a city with private investment, like a job centre, or a public investment, like a subway, the effect of this improvement is to elevate land values within the impact zone of these improvements, up to and even over the aggregate value of all these improvements. The main influence of this land price inflation goes to the landowner, and in particular to the land speculator who is smart enough to anticipate this effect — “getting in on the ground floor,” so to speak.

We see this influence now along the Broadway subway corridor, where land values have more than doubled in just a few years and for many strategic parcels increased by 1,000 per cent.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz made his reputation for proving that the value of these changes, embodied in land price, met or exceeded the aggregate value of these improvements, leading to the conclusion that this added value tied up in land price should be taxed at levels equivalent to these area-wide, or citywide, improvements. He proved that this could pay the full cost of the social and physical infrastructure needed by the city.

We don’t do that. We tax land value at about one per cent of its true value through property taxes. That leaves most of this gain on the table as capital gains, which is not taxed at anything like its full value and not until sold.

Anyway, all this sheds light on a problem: the financial benefits of our collective efforts go largely to the land speculator, and this land price inflation is by far the biggest reason why developers, who would love to provide affordable housing if they would not go broke trying, can’t do so.

The market, influenced by all these improvements, pushes land prices too high for affordable housing to “pencil out,” and sadly, when cities allow new density without any form of social benefit required, this too generally inflates land price, eliminating the hoped for affordability gains assumed to be the result of new density allowances.

Condon: Yes, it does sound a bit daunting when you realize that the very structure of urban real estate economics is working against your social ambitions — ambitions such as broad access to affordable housing.

When you look to the past for solutions there are places where you see we took a wrong turn on the land problem. Political economists like Adam Smith in the 1700s and Henry George in the late 1800s had real solutions to the land problem. They said if you are going to tax anything in a free market economy, tax not productive labour or entrepreneurs, but tax the land it all sits on — the landlord. If you don’t, the landlord will take more and more of the pie (or “products of production”) into the form of monthly rent or land purchase price.

Taxing the land at its “full rent value” shifts collective gains away from land price and into productive labour and capital. Both Smith and George claimed that this would allow taxes on incomes and capital gains to maybe be zero, taking the tax burden off of the two productive factors of production: workers and entrepreneurs.

Sadly their views did not win out. At the turn of the 20th century, when national land taxes were considered, Gilded Age barons, whose wealth was largely from the asset value of various lands, were strongly opposed. There is more on this history in my book.

Beers: So, what was the “wrong turn” we took back then?

Condon: The U.S. put its new national tax on income, not on land. Even Milton Friedman, famous conservative financial guru, wistfully said a land tax would have been best, but alas.

My own view is that a major shift of the tax structure away from income and capital gains onto land is today politically unlikely in the extreme. But happily, there are models for regional-scale actions that can mitigate the damage.

In fact, Vancouver is sort of famous for one of these: the community amenity contributions or CAC tax on “land lift.” This tax specifically targeted the moment of upzoning, in recognition that this was also the moment where land prices could increase by a factor of 10 or even more, to insist that 80 per cent of this new value would go to social benefit — benefits including affordable housing, parks, community centres and a first-class public realm.

The point here is that the CAC tax strategically targets the assessed change in land value consequent to the public policy change (upzoning in this case) being deliberated. In this way a locality can capture land value for local area social benefit.

This is a modern version of the general land tax economists have long recommended. It is modern because it captures this value locally, not nationally, and it is acquired at the incremental moments of city change using the ordinary rules of zoning policy. Less disruptive. Less revolutionary. More possible within our current framework of laws.

Vancouver has, sadly, over the years lost the plot on this one, where now in the Broadway plan this land lift model has been replaced entirely. To incentivize market-rate rental construction over condo projects we are streaming what would have been land lift to the city to private developers so they will agree to finance market-rate rental construction.

A more direct model is flat-out “density bonusing” for affordable housing. Municipalities can simply institute a requirement that a certain, hopefully large percentage of new units are perpetually affordable for households making average regional income and below.

This requirement puts downward pressure on land price and with development land price. If developers know they can’t build market-priced units for global buyers on a certain parcel of land, they won’t bid up its price. The price of the zoned-for-affordable land will adjust to the lower profits that can be made.

I suggest that 50 per cent permanently affordable is a reasonable benchmark for large, zoned parts of Vancouver going forward.

In my view the very best model for density bonusing comes from Cambridge, Massachusetts, where they allowed double density anywhere in the city — but only in return for 100 per cent permanently affordable housing.

The point again is this: in Cambridge, if you want to sell your land into the land market, you can sell at present market value under current zoning. If you want to double the density, fine, but the rents have to be at permanently affordable levels. To make the second case “pencil out,” the land price residual (i.e., your offer to the landowner) should not end up much higher than the market price under current zoning.

In short, the Cambridge model incentivizes affordable housing and at the same time suppresses land speculation by placing a ceiling on what the development land can sell for.

Beers: Hmm. How long has Cambridge had those zoning rules in place, and have significant amounts of below-market housing resulted? Did the investors respond, activating the private equity market to fund below-market housing, which seems the elusive dream?

Condon: Let’s see. Since the Cambridge bylaw was passed a few years ago, the number of housing units in the pipeline is pushing 1,000, which is a big chunk for a small urban city of just over 100,000 residents. I also think this number represents the majority of higher-density units built citywide during that same period. In that sense, its success certainly proves the method — that is of shifting the market towards the non-market mentioned earlier.

As for financing, the money came mostly from the financial markets at prevailing rates, but with the government assuming financial risk. This is basically the financial model used here in the 1970s to the 1990s to get places like False Creek South and Champlain Heights up and running. Again, we are not talking about taxpayer-subsidized housing but managing the land markets to stream zoning-related increases in land value away from the already overstuffed pockets of speculators into social benefit instead.

Beers: OK, but what about massive government investment in below-market housing that I hear some left-wing affordability advocates calling for? Some real estate economists argue that’s not effective because we are at a point where you can never really build enough and it creates a lottery for the lucky few who get the housing. They tend to say the government should increase welfare payments and other cash subsidies for low-income people to help pay market rents.

Another option you haven’t mentioned yet, but I’ve heard you suggest in the past, is using a lot of publicly owned land to build below-market housing — like public golf courses — because that gets around the land speculation issue.

Condon: I am for an all-hands-on-deck strategy to find ways to use our land base for social good.

The provocative proposal for the golf course restructuring makes sense because it too is a way to leverage global investment for local social benefit.

There are other ways, such as predetermining a land tax on development, as passed by Vancouver city council in 2018, for lands along the upzoned Broadway corridor. The tax was $340 for each additional interior square foot over current zoning. Sadly, this lost its effect thanks to a later council decision to shift to largely market rental units, not condos, along the corridor. Rentals were, and are, exempted from this tax.

Beers: Right, so to boil it down, let’s presume B.C. Premier David Eby and Vancouver Mayor Ken Sim are in a book club, and they read yours. Naturally, each decides to appoint you their special adviser on housing policy. Right off, what key things would you advise them to do?

Condon: An extremely unlikely scenario, I must say. But I would offer the following.

In the shorter term I would ask them to extend rent control beyond the tenant to the unit itself — so called “vacancy control.” This also has the benefit of making rental district lands less attractive to the global real estate investment trusts, or REITs, by reducing the speculative value of these city lands.

Second, starting no later than Monday, do it like Vienna did — by renting city lands for NGOs or co-op corporations to build on at prices that match what affordable rents can amortize. There are many parcels available.

Over the longer term, do not allow new density unless 50 per cent or more of the new units are permanently affordable. Increasing this from its current policy of 20 per cent below market to 50 per cent “permanently affordable to median wage earners” may slow development in the short term, but in time the land markets will adjust to this new requirement.

You see, within the next 30 years, the large majority of all private parcels in the city will be sold to someone. And when that happens, if my advice is followed, those parcels will be sold at land prices that are “market” prices at that time — prices that you will have not yourself inflated with the kind of unconditional upzoning we are allowing today unfortunately.

This is a process of what you might call “disciplining the land market.” Currently the land market is very undisciplined in Vancouver. In fact, built into how our city land markets are working is an assumed large annual increase in urban land value inflamed by allowing new market density citywide — as we have done.

Unless this trend can be slowed, the market will likely never be able to deliver affordable housing. We are currently just feeding the land price inflationary beast.

Disciplining the land markets via a suggested 50 per cent permanently affordable requirement is, I would argue, a locally practical way to hold down urban land prices. Vienna and Singapore, two very good precedents, did something similar. They both shunted more and more of their urban land beyond the reach of the global market, all by managing land value.

Vienna did it by taxing residential land at a high rate to drive down its speculative value while producing the revenue needed to purchase city land for affordable housing.

Singapore had an easier time of it in one key respect. Much of their urban land belonged to the city, and still does. In Singapore the city rents out the land that housing sits on to new residents at affordable rates. Residents thus own the apartment unit itself, sans land value. That lets homeowners build equity on their unit but not the land.

But of course, having Premier Eby and Mayor Sim embrace and advance these policies is an impossible dream, because both of them are touting the exact opposite approach — a kind of “trickle-down housing” solution that assumes government impediments, not land speculation itself, stand in the way of cheaper housing. They both support releasing development from most of the social betterment requirements, in the faith that this will lower prices.

It won’t. It will just make landowners richer.

The recent raft of housing bills passed by the B.C. legislature last November are illustrative of what is now an international trend. All three bills (44, 46 and 47) remove local policy control over city building. They justify this approach, remarking that “getting out of the way of the private sector,” (or words to that effect) will make housing cheaper.

But hold on! Vancouver is literally world famous for adding, over the entire post-Second World War era, proportionately more new market-rate housing units than any other North American centre city. It flowed from Vancouverism.

If adding density to an already built-out city automatically led to a more affordable city, Vancouver should have North America’s cheapest housing. It has North America’s most expensive.

David Beers is the founding editor of The Tyee and serves as current editor-in-chief. Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in landscape and livable environments at UBC’s school of architecture and landscape architecture.

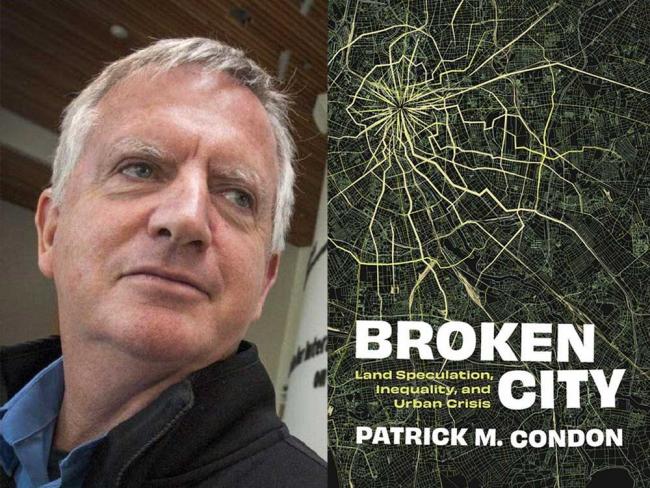

[Top photo: UBC professor of landscape architecture and urban design Patrick Condon discusses his provocative new book. Photos supplied.]