Articles Menu

Nov. 14, 2025

A small, oily fish at the heart of B.C.’s coastal food web will likely disappear without an immediate moratorium on commercial herring fishing, say Saanich First Nations Hereditary Chiefs and conservation groups.

“The way things are going, we will see the end of Pacific herring in our territory,” said Chief Eric Pelkey of the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council, recalling when prolific herring in the Strait of Georgia formed a vital part of Indigenous diets.

Since the advent of industrial fisheries in the 1930s, herring stocks around the B.C. coast have shrunk precipitously. Increasing pressure to produce fish meal and fish oil contributed to a population collapse and fishing closure in the 1960s.

The fishery reopened in the 1970s with a focus on roe.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, known as DFO, wants to increase fishing quotas next year in the Strait of Georgia, the healthiest herring spawning area, and is considering openings in other areas.

DFO spokesperson Mo Qutob said in an emailed statement that increased quotas are justified as “overall abundance of herring has increased since lows seen in numerous areas during the mid-2010s.”

A draft plan for the 2026 commercial herring fishery in the Strait of Georgia calls for a catch of 13,050 tonnes or 14 per cent of the estimated herring biomass.

The Strait of Georgia catch was halved to 10 per cent from 20 per cent in 2022 when a link was recognized between disappearing herring populations and falling numbers of wild salmon, but the percentage has now edged up.

Another proposed increase is in Prince Rupert District with an eight per cent harvest rate, up from five per cent.

And Qutob said commercial fisheries are also possible in the Central Coast and West Coast Vancouver Island regions based on “scientific stock assessments, precautionary management procedures and input from First Nations, stakeholders and the public.”

The proposal to increase the herring catch is incomprehensible to those fighting to restore stocks. They point to the importance of herring to other species, including chinook salmon, the primary food source of endangered southern resident killer whales.

It also threatens financial spinoffs from businesses such as whale-watching and birding that bring in millions of dollars more than the $5-million landed value of the herring roe fishery, say advocates.

“Herring are the foundation of the coastal food web, sustaining salmon, halibut, whales, seabirds and countless other species, as well as the communities that rely on them. Yet, in some areas, this forage fish has shrunk to just one per cent of its former population and, in others, they’ve disappeared completely,” said Sydney Dixon, Pacific Wild marine specialist.

The Strait of Georgia contains 44 per cent of B.C.’s spawning herring, meaning it is vitally important for preservation of stocks.

“I think fishing down the food web, catching forage fish, is really short-sighted for the long-term viability and health of our marine system,” said Dixon, who wants all commercial herring fishing in the Strait of Georgia suspended until populations recover.

For the W̱SÁNEĆ’s Pelkey, the 2026 draft plan is the final straw.

“We have come to the point where we are not going to take it any more.... Now we are moving forward to take legal action against the government,” said Pelkey, speaking at last month’s Victoria Herring Symposium, where participants considered ways to turn the tide for Pacific herring.

“We are going to fight to save the herring,” he said.

In November 2024 W̱SÁNEĆ Hereditary Chiefs issued a declaration calling for a moratorium on all commercial herring fisheries in the Strait of Georgia to provide “overwintering and migrating herring with a refuge from the commercial fishing pressure that is present almost year-round.”

That declaration — like a previous 2020 plea for a moratorium — was ignored by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Pelkey said.

“We feel like no one is listening. DFO is not even listening to its own science,” he said.

The W̱SÁNEĆ Hereditary Chiefs, assisted by the Herring Conservation and Restoration Society, Georgia Strait Alliance and Ecojustice, have asked for a legal opinion on whether to proceed with a court case, based on the right set out in the 1852 Douglas Treaties “to fish as formerly.”

About $20,000 has been raised for a legal opinion from Ratcliff LLP, a Vancouver law firm. When that opinion is submitted in the new year, Hereditary Chiefs will plan their next steps, said Jim Shortreed, Herring Conservation and Restoration Society president.

Options include a civil claim for breach of the treaty right to “fish as formerly,” which could lead to a trial, or an application for a judicial review of one of DFO’s commercial herring-related decisions in the Strait of Georgia, according to a briefing note from the law firm.

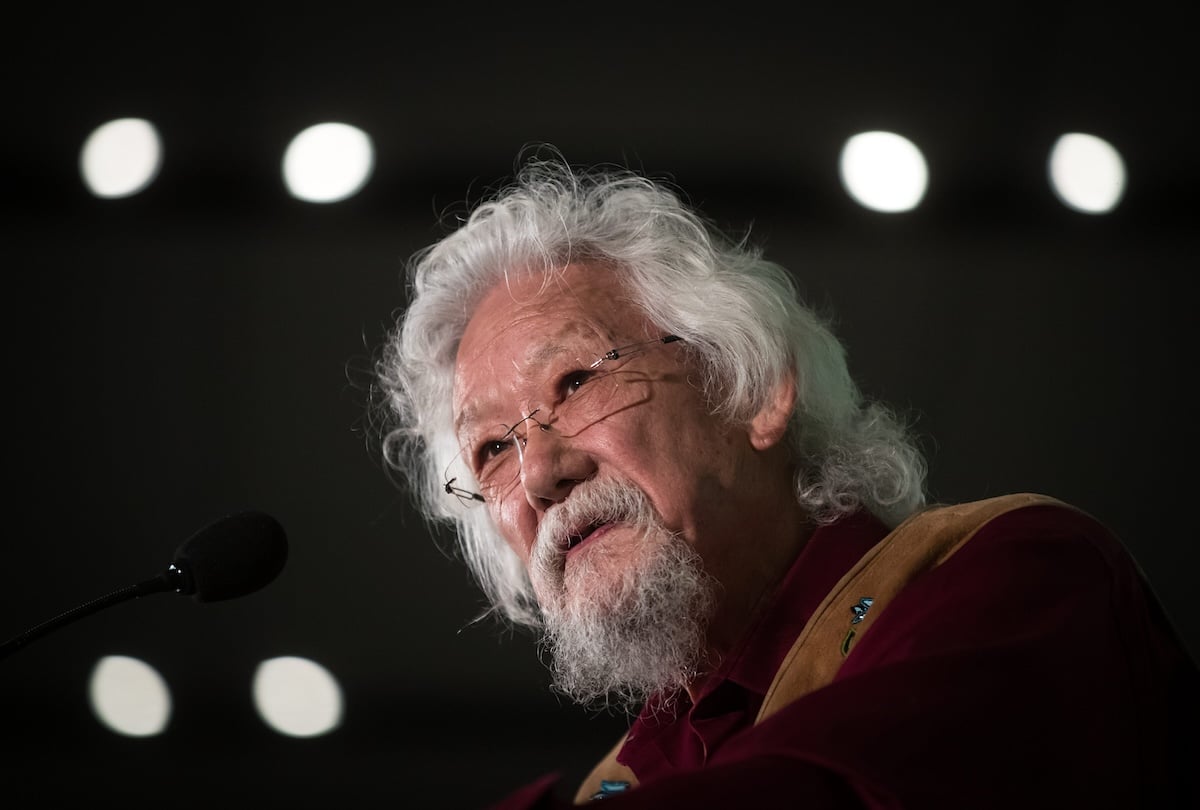

Environmental activist David Suzuki said in a burst of frustration at the symposium that threats of legal action need to be backed by direct action.

“This fishery should be stopped now,” said Suzuki, adding that supporters must be willing to put their bodies on the line and get arrested.

“I am ready to go and stand on the line.... We have got to have the occasion so that we get arrested. I don’t want to end up just waving a bunch of placards,” said Suzuki, speaking as an individual and not for the David Suzuki Foundation.

A gathering — likely to include Suzuki — will be held outside DFO Vancouver offices at 200 Burrard St. on Monday to deliver responses to the draft plan, including recommendations for the herring harvest, Shortreed said.

“Our recommendation is, as ever, pause the fishery until stocks recover in the Strait of Georgia,” said Shortreed, adding that all previous recommendations have apparently been electronically shredded by DFO.

“Over the years I have been submitting my herring harvest recommendations by email and getting nothing in return. No receipt of submission even. That is probably because my recommendation [is] a halt to all industrial kill fisheries until I can fish herring in Victoria as I used to,” he said.

Monday is the final day for public input, said Shortreed, who is asking anyone interested in saving herring to provide responses to DFO.

In addition to fears that herring stocks are collapsing, the roe fishery represents an inherent waste of a resource, say opponents. The herring are killed and eggs stripped from females, largely for export to countries such as Japan, while most adult fish are ground up for products such as pet food and fish meal.

“The vast majority of herring that is caught in B.C. is being shipped overseas. It is not being eaten locally. Why would you risk British Columbian food security?” asked Dixon.

In contrast, First Nations and some other local fisheries use a roe-on-kelp method where eggs are collected from kelp or cedar boughs and the fish continue to breed for future years.

According to DFO, Strait of Georgia herring stocks remain in the healthy zone and stocks around Prince Rupert and the west coast of Vancouver Island are now healthy enough that they “may support commercial fisheries under precautionary management frameworks.”

It is not accurate to claim all areas have been decimated, Qutob said.

“Where stocks are at lower levels of abundance in other areas, commercial fisheries have been brief or closed.”

Robert Morley, chair of the Herring Industry Advisory Board, which provides advice to DFO on the commercial roe fishery and the food and bait fishery, said science shows herring are abundant in the Strait of Georgia and a 14 per cent harvest rate is “absolutely sustainable.”

A study conducted last year for the Herring Industry Advisory Board shows stocks have remained relatively steady for the last 10 years, dropping slightly in 2023 and 2024 and increasing in 2019 and 2020.

The fishery, including processing, brought in $30.4 million last year, including $5 million that went to Indigenous communities, says the study. About 80 per cent stems from the roe fishery, and the remaining 20 per cent from the food and bait fishery.

“We are in the process of updating the numbers for this year, but with the expected slight increase in quota, and with good signs from the market, we expect better economic outcomes this year,” said Morley, who is also executive director of the industry-funded Herring Conservation and Research Society.

The fishery provides 1,371 jobs in fishing, processing and spinoffs, of which 274 are in Indigenous communities, the study found.

However, Pelkey remains convinced that overexploitation is responsible for the lack of herring in areas where the fish were previously abundant.

“Herring are the basic food source for everything that lives in the ocean, including us,” he said.

“If we give up on herring, we give up on life in the Salish Sea.”

[Top photo: Increased herring catches proposed for 2026 could wipe out stocks of the critical food source for salmon, halibut, whales and seabirds, say environmental groups. Photo via Pacific Wild.]