Articles Menu

Late last winter at Vancouver’s Maritime Labour Centre, city councillor Geoff Meggs spoke at the launch of a regional union-backed social justice organization called the Metro Vancouver Alliance. Meggs is a long-time anchor of the British Columbia labour movement. In the 1980s, he was the editor of the fishers’ union newspaper and the personal editor for the legendary Canadian communist Ben Swankey. In the ’90s, he was a high-level adviser in the B.C. NDP government. And in the 2000s, he migrated, with many of his contemporaries, into civic politics where he helped build Vision Vancouver, the labour-supported party that has held city hall for two terms and appears set to take a third this November.

But from his city council seat as a founding member of Vancouver’s Third Way party, Meggs has helped lead Vancouver to some unflattering distinctions: it has the second most expensive real estate market in the world, the highest homelessness numbers in its own history, and the highest child poverty rate and greatest income equality gap in Canada. Meggs, an architect of inequality, was celebrated at the inauguration of a social justice organization in the very city he has helped to stratify. How did this all happen?

Vision Vancouver’s brand of progressive politics might appear a local issue, but the concept of hegemony helps us understand Vision’s relevance for urban neoliberalism more broadly. The Italian revolutionary Antonio Gramsci drafted his influential concept of hegemony within the walls of Mussolini’s fascist prisons. In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci defined hegemonic power as the combination of force and consent within a “historic bloc” of classes and social groups that dominate economic, social, and cultural life. Key to hegemonic power is the formation of the “common sense” of the day: the embedded beliefs and assumptions that people accept as natural, like that tax cuts fuel economic growth, that gentrification is inevitable, that economic growth is healthy, or that locally produced food is more ethical.

In contrast to Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, many leftists today explain the power of neoliberal governance with a conspiracy theory that goes something like this: workers support neoliberal governments because of their corrupt labour leaders, and government policy is dictated by big corporations who pull the strings of corrupt political parties with lavish campaign donations. Like most conspiracy theories, this is a tempting notion because it presents us with a simple image of a puppet master at the top, controlling the hapless masses. We like this idea because it forgives us our mass complicity in nets of injustice and simplifies the project of change. And, like most conspiracy theories, it also protects us from the uncomfortable truth: urban neoliberal politics have a vast social base.

Vision Vancouver emerged as the progressive wings of the ruling and middle classes seized political and economic leadership from the conservative social bloc that initiated the neoliberal revolution in B.C. I call the historic bloc that Vision represents philanthrocapitalist because, to their supporters, Vision represents a friendly alternative to the ugliest aspects of capitalism. Taking moral cues (but not policy) from social democracy, philanthrocapitalism aims to replace taxation and state-driven redistributions of wealth with voluntary acts of charity and “innovative” micro-market projects. To sell their charity as social change, philanthrocapitalist leadership draws on potent cultural symbols associated with social justice and sustainability, obscuring structures of inequality and exploitation. In Vancouver, these cultural symbols draw from the vocabularies of environment, labour, and Indigenous struggles. Bike lanes are only the beginning. This past June, Vision formally acknowledged that the city rests on the unceded territories of Coast Salish Indigenous nations. Such gestures are lauded as progressive, and are borrowed from the platform of COPE, the civic party to Vision’s left, but they do not redistribute wealth, return stolen lands to Coast Salish nations, or intervene in capitalist accumulation in the city.

With the demise of social democracy – and its commitment to full employment, progressive taxation, and expanded social services – philanthrocapitalism became hegemonic in Vancouver by establishing a historic bloc made up of urban capitalists, urban labour unions, and the progressive middle class, presenting a moderate program billed as progressive while isolating more radical voices that could expose the illusions of a socially conscious capitalism.

In the mid-1980s, conservative parties began the restructuring of the B.C. economy, and particularly the economy in Vancouver, away from industry and toward finance and real estate development. By the time the B.C. Liberals took power on an austerity and anti-union agenda in 2002, the services employment sector had increased from less than 40 per cent of the Lower Mainland workforce in 1981 to 78 per cent in 2012, with the great majority of the work concentrated in Vancouver. This economic shift dovetailed with the Liberals’ union busting and cuts to social programs as well as with the potent free market discourse that grew to occupy every corner of official politics.

In the lead up to the 2005 civic election, amid the defeats of labour, the retreat of social democracy, and the shrinking imagination for alternatives to the free market, Vancouver’s then sole labour-backed party, COPE, split in two, with the right wing of COPE forming a new party: Vision Vancouver. Under a program of perpetual economic growth through perpetual real estate development (and the transformation of Vancouver into a resort city), Vision sought to crystallize in itself a new historic bloc, combining the fractured and short-term interests of sections of labour with the financial and investment interests of urban capital.

It is so often repeated that it may be the tag line of Vancouver: developers own city hall. And if it is with campaign donations that urban capitalists have bought city hall, then it is only logical that campaign finance reforms would divest them of the city. But, what if we think of campaign donations not as buy offs but as expressions of the economic power that animates political parties? A party’s campaign coffers are the political expression of a social bloc composed of different groups. With this view, election campaign donor lists might tell us which social, cultural, and ideological forces crystallize in a political party and also who is excluded from its hegemonic bloc. The problem is not located at the point of transaction between the party and its base but in the political and economic reality they orchestrate. The popular lefty Vancouver slogan “Developers Out of City Hall” points in the right direction but doesn’t account for an urban economy that rests heavily on real estate and the service jobs finance capital supports. It also tends to present city hall as the boss of the urban economy rather than the managerial branch. The solution, then, must go deeper than campaign finance reform. It must develop a politics based on human need rather than the constant growth demands of capital, and that means taking on the business class as a whole and not just its politicians.

Over three election seasons, Vision took in $1.1 million from its top 10 corporate donors, most of whom were real estate corporations and luxury goods marketers. Half of the B.C. Liberals’ top 10 2012 campaign donors were also top donors to Vision, including key real estate giants like Wall Financial, Redekop Construction, and real estate marketer Bob Rennie, who plays media huckster and fundraiser for both Vision and the B.C. Liberals. These corporate donors are not pro-labour. Under the name Five Boys Investment, Lululemon yoga capitalist Dennis “Chip” Wilson contributed $50,000 to the B.C. Liberals in 2012 and $50,000 to Vision in 2011. According to Forbes, Wilson is the 16th richest person in Canada with a net worth of US$1.8 billion. He is also a public Ayn Randian who produced a tote bag with the slogan “Who is John Galt?” referencing Rand’s super-capitalist literary manifesto Atlas Shrugged. David Aisenstat, a restaurateur and CEO of the Keg steakhouse chain, gave $100,000 to Vision in the 2011 election before red-baiting the NDP in the 2012 provincial election.

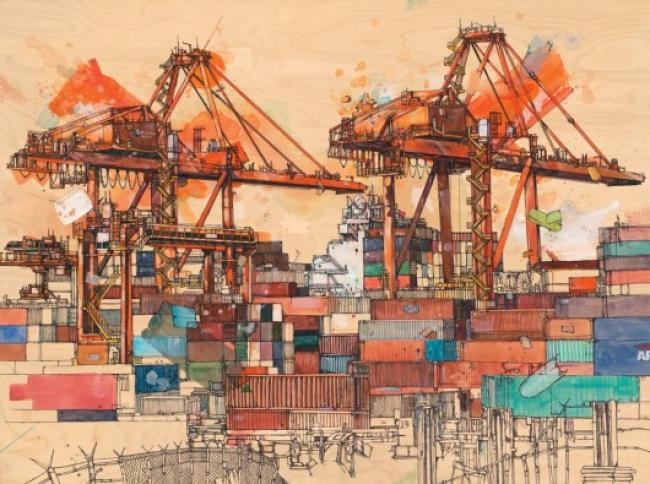

No Left Turns, 2013. Ink and acrylic on wood panel. Jon Shaw.

No Left Turns, 2013. Ink and acrylic on wood panel. Jon Shaw.

The single biggest donor to Vision Vancouver, however, is not a McCarthyist captain of industry. It is an ideologically driven group of wealthy social reformers: our philanthrocapitalists. No single person within the philanthrocapitalist group donated as much as the corporations, but they are a narrow ideological group, closely rallied around a common project, whose collective contributions are immense. A group of at least 49 individual donor groups affiliated with philanthrocapitalism donated more than $400,000 to Vision in just the 2008 and 2011 elections. The main players in this group are Joel Solomon and Carol Newell and their related groups: Tides Canada, Renewal Partners, Strategic Communications, and Hollyhock. These groups support large environmental organizations, fund social justice projects like the Pivot Legal Society, and are proud advocates of social change. So why are they cozied up to a party with right-wing libertarians? What is their role in Vancouver neoliberalism?

In a 2012 YouTube video from a San Francisco conference, Marian Moore, co-founder of a group called Play BIG, which rallies super-rich philanthropic donors, introduces a panel with Renewal Partners executives, Solomon and Kristin Hull. “I know that people want to align their money with their values,” says Moore. “Play BIG is about peers helping peers. It’s about subverting the dominant paradigm about money, and it’s about the liberation of money and the liberation of people.” She says she is a “steward of tens of millions of dollars” but that she was never interested in philanthropy until Play BIG showed her how large donations have meaning. “We’re at a time between times,” she says, “and we need pioneers.” The crowd applauds.

Solomon, a co-founder of Renewal Partners, is happy to be the pioneer that millionaires need. “We are here talking as pioneers who want to encourage others to take the risks they can take so that things can be invented and tested and experimented with, and that bigger, smarter players may come in and commoditize it effectively. And that would be success.” His mission is to create a sustainable economy from the city of Vancouver outward. His project is no less ambitious than reforming capitalism itself. “We need both radical action to demonstrate what can be, and incremental change, reformist change of capitalism, so it’s kinder and gentler and thinks about the long-term future and thinks about everyone instead of just the individual.”

The role of philanthrocapitalists in the neoliberal social bloc differs from both the corporate group and from labour. Philanthrocapitalism is the ideological glue, the discursive sparkle of social change that holds the social bloc together. When it comes to city politics, philanthrocapitalists direct reformist efforts away from hard economic frameworks like wages and rent toward voluntary spaces of social intercourse where super-rich donors can make their mark without disturbing profits. Philanthrocapitalist innovations like bike lanes, green spaces, private arts funding, and the striking of dramatic poses on environmental policy mobilize progressive cultural symbols to buffer the harsh realities of growing inequality. The positive language of change sweeps along Vancouver’s powerful middle class as well as those workers who imagine themselves as part of the middle class and identify with its tastes and values.

The historic bloc expressed through Vision Vancouver does not, however, include all the powerful, which is why it can sometimes appear progressive or as a lesser evil to more right-wing parties. To the south, the U.S. political theorist Adolph Reed Jr. has explained that the Democrats and the Republicans are both neoliberal parties but that the former embraces diversity while the latter opposes it. The pro-diversity neoliberalism of philanthrocapitalism excludes the more conservative, industrial, and resource extraction-based sections of the capitalist class who refuse to co-operate within philanthrocapitalism’s marginal limits and don’t share its aesthetic or cultural values.

When it comes to inequality, there is an ideological double duty at work in social policy like Vision’s homeless shelters or pro-gentrification “social mix” policies: first, the blame for systemic crises rooted in capitalism, colonial dispossession, white supremacy, and patriarchal violence is shifted onto the suffering individuals; then, these fields of individual suffering are set out to be managed by the free market in partnership with benevolent philanthropists and NGOs. In the name of care, philanthrocapitalism promises to institutionalize disenfranchised, low-income groups in highly regulated structures. Such policy does not, as Solomon claimed in his San Francisco address, make capitalism “kinder and gentler.” The philanthrocapitalist model of social change appears to work in Vancouver only because the new elite has inherited the fruit of the economic shift – pioneered by conservative neoliberals – toward real estate, finance, and investment capital. With the industrial working class pushed aside, the new elite is developing a resort city free of urban blight.

Despite their high pretensions, urban neoliberals are still part of the ugly capitalism they find distasteful. Vancouver is, according to Business in Vancouver magazine, “a world centre for mining exploration” with more than 1,200 exploration companies headquartered alongside its bike lanes and view corridors. Provincial politicians don’t have the luxury of such civic greenwashing. In the winter of 2014, Brian Topp, the B.C. NDP’s chief strategist, reflected on the NDP’s catastrophic 2013 election loss and blamed it squarely on their decision to campaign against the Kinder Morgan pipeline, saying, “We all take our collective responsibility for bad decisions.” Within the limited framework of neoliberal economics and politics, the NDP failed to develop a political and economic alternative to tarsands jobs for their rural working-class base. Vision’s social bloc is insulated from such dilemmas by the super-profits reaped from Vancouver’s Pacific Rim power position in the global economy, by the service sector and short-term construction jobs these super-profits support, and because the profits from resource extraction in the rest of B.C. flow into corporate offices and the bloated wallets of CEOs, not in Terrace and Kitimat, but in Vision’s Vancouver.

Urban radicals might take a lesson from the failures of the B.C. NDP who rejected a pipeline but offered no alternative to its economic “common sense.” What, after all, is our alternative to the perpetual real estate development, gentrification, and resource extraction of neoliberalism? If the death of social democracy opens up space for more radical alternatives, then to realize them we need a new historic bloc capable of forming its own common sense, its own common vision of practicable economies, social relations, and individual and collective health. Such a bloc would have to establish its basis not only among the most vulnerable and oppressed, nor only at the left fringes of organized labour or student life, but in a broad assemblage of social groups which are excluded from the neoliberal city. In forming a counter-hegemonic bloc, we must begin from where we find ourselves: with a working class that includes those women, migrants, volunteers, non-capitalist producers, and unwaged workers who produce our social wealth. And we must begin by taking on a living legacy of colonialism that will not be corrected by official acknowledgement or recognition but instead by reparations, sovereignty, and autonomy for Indigenous nations rising.

Just because Vision’s brand of progressivism operates in the realm of ideology does not mean we should give up on popular ideas and attitudes as a terrain for political struggle. Gramsci argues that, in a historic bloc, “a popular conviction often has the same energy as a material force.” We might engage this terrain first by understanding neoliberal power as a system rather than as a conspiracy and then developing our structural critique and therefore our structural vision for change. From this critique, we will be better able to unite different communities by seeing how their distinct oppressions connect (like, for example, how rural displacement due to resource development mirrors urban gentrification). The goal of this counter-hegemonic bloc would not be to maintain its alternative vision at the margins of society but instead to help create a common image of a world beyond capitalism itself – and to assemble the organizational structures to help us get there.

Ivan Drury is a writer, organizer, and aspiring historian who has lived on unceded Coast Salish territories in Vancouver all his life. He currently organizes with the Social Housing Alliance and is on the editorial collective of the Downtown East newspaper.