Articles Menu

After Jean Swanson is done cleaning out the “dust and the mousetraps” from her new office in City Hall, she’s thinking of hanging two sheets of paper on the wall with words of guidance from her friend Kshama Sawant.

In her campaign to get elected to Vancouver city council, Swanson often named Sawant as her political inspiration. Though Swanson is three decades older than Sawant and doesn’t personally identify as a socialist, the two women share a lot in common. They are political outsiders who view themselves as representatives of social movements engaged in a class war between society’s wealthiest one per cent and a working class majority.

When Sawant came up to Vancouver in October to make a speech endorsingSwanson’s campaign, along with the other candidates running with her party, COPE, Swanson took notes. “There’s a lot of good advice,” she said.

Swanson hopes that if she sticks to these principles, she can swell the ranks of progressive organizations, turn out large new blocs of renters to vote in elections, pass aggressive policies like a rent freeze and a mansion tax, end homelessness and begin to address the social dislocation caused by decades of unchecked international investment in real estate. It goes without saying that these are ambitious goals for a 75-year-old who’s never been on city council. “That will be a huge battle,” she admitted.

Yet some people in Vancouver’s business community worry that it’s a battle Swanson has a shot at winning. “She’s a devout, dated radical who wants to redistribute wealth, so if you’ve got any wealth in Vancouver you have to be fearful with her on council,” Neil McIver, portfolio manager and owner of McIver Capital Management at Canaccord Genuity and chief strategist for Wai Young’s Coalition Vancouver party in the 2018 municipal election. “The concept of Vancouver being a business-friendly city is out the window.”

I asked McIver if it eased his concerns that Swanson is only one of 10 city councillors, and that five of those councillors belong to the more business-friendly NPA. “I think she’ll contribute to really what I believe will be a broken city council,” he said. McIver thinks the NPA’s five votes on council could be neutralized by the five progressive votes from three Green councillors, OneCity’s Christine Boyle and Mayor Kennedy Stewart – and that Swanson will hold the balance of power.

“She is going to be that sixth vote that will take everything to the level of the class warfare that she advocated during the campaign,” he said.

‘We have rights and we have power’

In mid-November, a couple dozen people showed up at the steps of City Hall for a protest organized by the Vancouver Tenants Union. The group, which worked closely with COPE and Swanson during the election campaign, was there to support a motion Swanson had introduced banning renovations on rental buildings that result in exorbitant rents and evictions – a process known as “renoviction.”

As the demonstrators held up a banner reading “Tenant Power,” which was accompanied by an image of a key with a fist inside it, a security guard emerged from City Hall and told the protest to move elsewhere. “You cannot block the stairs,” he said. Soon an argument broke out, with one demonstrator saying, “I’ve been to like 50 rallies on these stairs.”

Just then, a bemused-looking Swanson walked out the doors. The security guard stopped trying to vacate people from the steps and went inside. “We have rights and we have power, but most people don’t know what to do with it and they don’t know how to access it,” Audrey Siegl, a member of the Musqueam First Nation and a former COPE candidate, told the rally. “Don’t stand and accept when they say ‘you’re not allowed to be on these stairs.’”

A few minutes later Swanson took the microphone. “Hi guys, thanks so much for coming out,” she said. The new councillor had spent the morning in one of the first council meetings since the civic election, which had featured sparring over what time speakers for her motions would actually get to appear. “Just on a personal level, it’s so nice to see you all here so I can be grounded in some reality after two hours of sitting in there,” Swanson said. “I’ve got to run in now, but keep up the hard work.” She briefly raised her fist in the air and then left.

Off to the side I ran into Vince Tao, an activist involved with the fight against market-rate housing at 58 West Hastings St. and a prominent figure in the campaign to block Beedie Living’s 105 Keefer project in Chinatown last year. I asked him what makes people like Swanson different from traditional politicians. “This is what Jean represents,” Tao said, gesturing to the demonstrators on the stairs. “This is why she’s powerful.” So would having her in office help activists like him be more effective? “It’s going to make it a little easier for us, but there’s still so much to fight,” he said.

A few days later I phoned up Pete Fry, who in October was elected to his first-ever term on city council with the Green Party. I asked what he thought of Swanson’s political style. “It’s not just pure force of will that gets things done, it is a series of negotiations, it is a series of compromises. What those look like remains to be seen, but certainly I think that might be a reality that will have to be faced by Jean in the coming months,” he said.

Vancouver’s forgotten radicalism

Several times during her election campaign Swanson talked about another political inspiration of hers, Harry Rankin, a self-declared socialist who lost his 1986 campaign for Vancouver mayor to young NPA candidate and future B.C. premier Gordon Campbell. When Rankin was on council with COPE in the 1970s and 1980s, Swanson saw him as an ally inside the political establishment for social justice groups like the Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA).

She recalled one event in particular that showed how grassroots movements and elected politicians can work together. “When I was at DERA we had this problem with stores selling rubbing alcohol as a beverage and we complained to the city inspectors and they said ‘oh no, it’s not happening,’” Swanson said. She approached Rankin and he asked for evidence. So she “collected a couple garbage bags of empty rubbing alcohol bottles” and then dumped them out on a table during a city council meeting. After that the inspectors took action. “I wouldn’t have been able to do that if [Rankin] hadn’t been there,” she said.

To younger people who have only known Vancouver as a gleaming haven for international investment capital, it can be hard to imagine that socialists like Rankin, not to mention the decades of left-wing activists and politicians who came before him, used to exert serious political influence. “There’s a whole generation that simply doesn’t know it existed,” Teresa Alfed, director of the recent documentary The Rankin File: Legacy of a Radical, told me. “I don’t think it’s an accident we’ve forgotten or become dissociated from our radical roots in this city.”

It’s hard to put an exact date on when that happened. But it certainly accelerated in the mid-2000s, when COPE mayor Larry Campbell convinced a more moderate faction of the party — described by media at the time as “COPE-Lite” — to split off and form the political party Vision Vancouver. Under its three-term mayor Gregor Robertson, Vision eschewed class-based confrontation in favour of policies it believed would help social justice activists and corporate developers at the same time.

“On a more banal level, Jean now has access to information, planning documents, staff reports and things that previously needed an FOI [request] or a long wait from a sluggish councillor,” Nathan Crompton, an editor at the Mainlander and an activist who works with the Our Homes Can’t Wait Coalition, wrote to me in an email. “Jean also has paid staff and can conduct research to determine what is actually needed in communities across the city.”

These new resources, along with Swanson’s recent motions on renovictions and social housing at 58 West Hastings, don’t quite add up to a revolution – at least not yet. “As it is now, the opening demands of Jean and COPE are very small and reformist, they barely scratch the surface of capitalist and colonial power in this city,” Crompton explained. “But the theory…is that these opening reforms can begin a process of empowerment and concrete possibility for ordinary people and for our movements.”

For now Swanson is just trying to adjust to the realities of her new job. “It’s been really, really busy,” she said. “I feel like I’ve jumped into the fire, that’s for sure.” When she gets worn down, she thinks of all the “tenants, low-income and working folks” who are counting on her to help create transformative change. And Swanson, in return, is counting on them to keep her going. “It’s nice to know someone has my back on the outside,” she said.

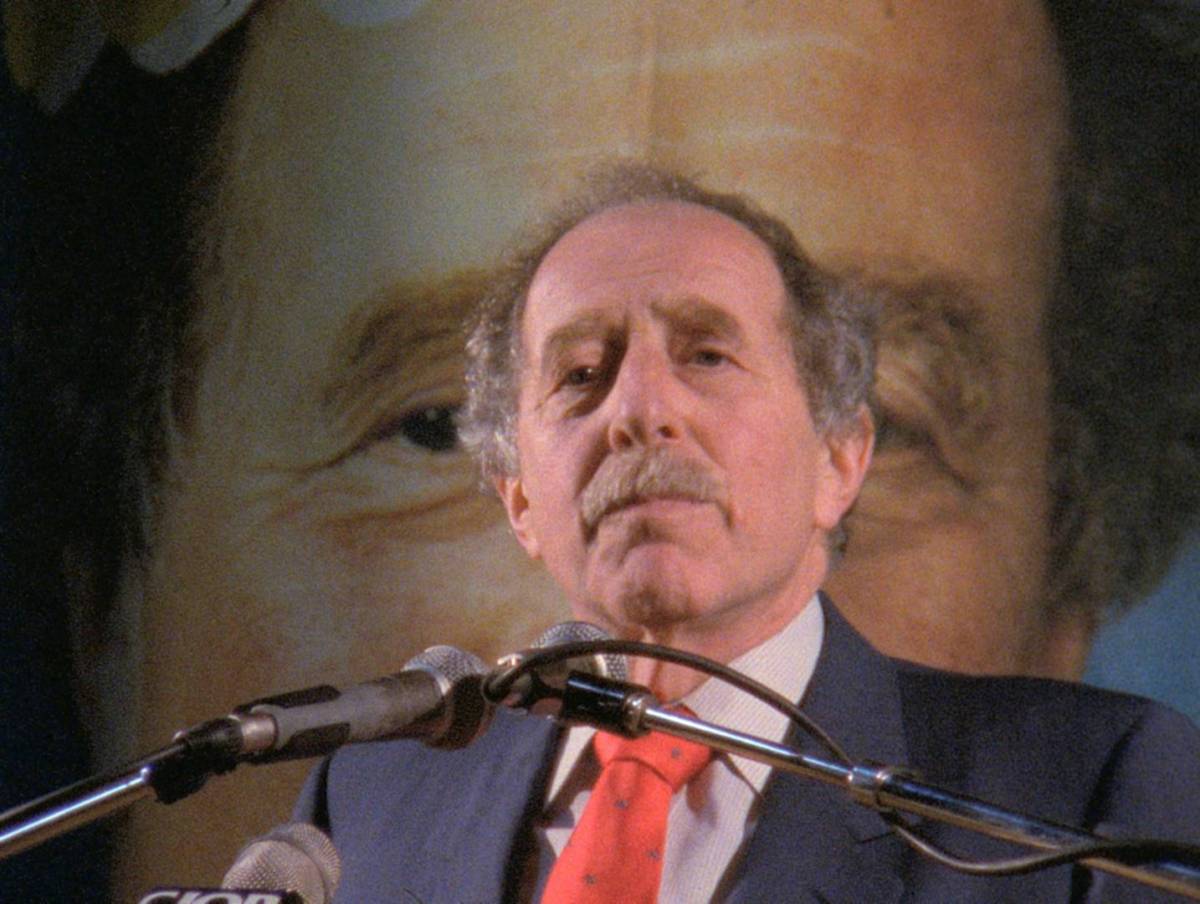

[Top photo: ‘I feel like I’ve jumped into the fire’: After 30 years as an activist outsider, Jean Swanson is now finding her way inside the halls of power in Vancouver. Photo by Christopher Cheung.]