Articles Menu

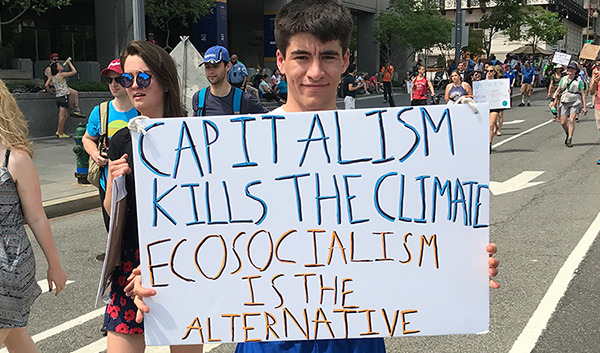

How can we reconcile social struggle and environmental struggle? This question poses problems for trade unionists. To avoid a climate catastrophe, it would be necessary to reduce economic activity, to suppress useless or harmful production, to give up a substantial part of the means of transport … But what would happen to employment then? How can we avoid a surge of unemployment, a new rise of poverty and precariousness? In today’s relationship of forces, in the face of financialized and globalized capitalism, these challenges seem impossible to meet.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) has drawn a radical conclusion: under the guise of fine words in favour of the “just transition,” it has chosen to accompany the evolution toward an impossible green capitalism. The Vancouver “Resolution on combating climate change through sustainable development and just transition” (2010) is clear: this document advocates a transition that “without endangering industries’ competitiveness or putting excessive pressure on state budgets” (Article 5). We feel that we are dreaming: the demand for the respect of competitiveness is not even accompanied by a reservation concerning the fossil fuel sector, the main cause of climate change! However, without breaking the power of this sector of capital, it is strictly impossible to avoid the climate catastrophe.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) has drawn a radical conclusion: under the guise of fine words in favour of the “just transition,” it has chosen to accompany the evolution toward an impossible green capitalism. The Vancouver “Resolution on combating climate change through sustainable development and just transition” (2010) is clear: this document advocates a transition that “without endangering industries’ competitiveness or putting excessive pressure on state budgets” (Article 5). We feel that we are dreaming: the demand for the respect of competitiveness is not even accompanied by a reservation concerning the fossil fuel sector, the main cause of climate change! However, without breaking the power of this sector of capital, it is strictly impossible to avoid the climate catastrophe.

The ITUC wants to believe that a “democratic governance” integrating the “just transition” would open up “new opportunities,” that it would create massively “green jobs,” good and “decent.” This is wishful thinking. Capital invested in the “energy transition” in no way derogates from the ruthless capitalist offensive against wages, working conditions and trade unions. Germany is at the forefront of both renewable energy and expanding an underclass of poor workers. In many countries, governments use ecology to dismantle union strongholds in traditional sectors.

Developing a genuine trade union alternative to the class collaboration policy of the ITUC leadership is of strategic importance. The working class occupies a decisive position in industry and services. Without its active participation, an anti-productivist transformation of the economy will remain impossible. But how to win workers to the struggle for the defence of the environment? That is the question. The answer is difficult. All the more difficult because the balance of power is deteriorating and the poison of division is spreading in the working class.

What must be done? To begin with, the problem must be posed correctly on the theoretical level. For here we are touching on a fundamental question: capital is not a thing, but a social relation of exploitation that subjects workers more firmly than chains would. Like it or not, this system compels every worker to produce more than is necessary for the satisfaction of their needs, and to realize this production in the alienated form of the commodity. So, to collaborate in productivism, which ‘exhausts the only two sources of all wealth: Nature and the worker’ (Marx). Today this collaboration is becoming more and more unnatural, since it threatens the very survival of humanity. But in “normal” conditions, capitalist competition imposes it on everyone.

We must therefore get out of “normal” conditions, out of the competition of everyone against everyone. How? By collective organization, by the action of the exploited for their demands. “The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves” (IWA 1864). This famous phrase of is more than ever valid. Faced with the ecological crisis, the enormous problem of the submission/ integration of workers to the productivist race of capital can only be surpassed by self-organized struggle. Practical conclusion: any collective resistance against austerity, dismissals and closures must be supported, even critically (when it is not really democratic, or its starting point is antithetical to the defence of the environment). Because one thing is certain: workers who are defeated in the immediate economic fight against austerity will not progress to a higher political consciousness, integrating the ecological question.

Workers’ control and democratic self-organization can work miracles in terms of consciousness. Even at the level of an enterprise. A remarkable example was provided in 1975-1985 by the “surplus workers” of the glassworkers’ sector in Charleroi: following the fight against the closure of their company, they imposed their conversion in a public enterprise of insulation/renovation of housing (the enterprise was created but sabotaged later by politicians and employers).

Such examples, however, remain exceptional. In general, the formation of an ecosocialist consciousness requires an approach and experiences at a broader level than the enterprise. It is at the inter-sectoral level that trade-unionism can best pose structural demands consistent with an anti-capitalist approach to the transition. To take some examples: the extension of the public sector (free public transport, for example); the expropriation of the fossil fuel sector (a condition sine qua non for a rapid transition to renewables); the radical reduction of working time, without loss of salary (a condition sine qua non for reconciling decreasing output and employment).

But the programme and the struggle are not enough. An ecological and combative trade-unionism requires us to look beyond the inter-sectoral level. A strategy of convergence with other social movements – peasant, youth, feminist, ecological – must be conceived. This implies abandoning the misconception that work is the source of all wealth. In truth, the exploitation of wage labour presupposes the appropriation and exploitation of the natural resources which necessarily provide the material object of labour on the one hand, and on the other the patriarchal exploitation of care work, carried out mainly by women and “invisible” in the context of the family. The capital-labour contradiction is thus embedded in a broader antagonism between capital, on the one hand, and reproduction on the other.

If it places itself at the heart of this antagonism, trade-unionism can get out of being on the defensive, make alliances with other social movements, develop with them an attractive ecosocialist project. It is not a question of reviving the chimera of a progressive social transformation by the accumulation of micro-experiences that are supposed to make it possible to avoid a global trial of strength. On the contrary, it is a question of preparing this trial of strength at the territorial level, by systematically developing practices of control, solidarity, self-organization and self-management. These will encourage the exploited and oppressed to take things into their own hands, to become aware of their strength, thus promoting an overall ecosocialist and feminist awareness that will strengthen trade-unionism.

This strategic proposal will seem to some people to be far removed from the real relationship of forces. Let them not forget this: the relative calm that reigns on the surface of social relations is misleading. Capitalism is mutilating life and nature. Human nature in particular. The majority of the population are forced to exhaust themselves and to exhaust the environment in alienated work, more and more useless, ethically unbearable and which produces a miserable existence. The explosive material accumulated in this way can release its energy to the left or to the right.

And the climate strikes by young people over recent months in an increasing number of countries are only one positive example of this dynamic – which also is shown by movements like Black Lives Matter and the Women’s strikes planned again for March 8 this year. The political discussions, including on issues such as productivism and growth, taking place among young climate activists need to be spread in trade union circles – as well as the energy and militancy of their mobilization.

It is an understatement to say that trade-unionism has an interest in the liberation on the left of the social energy accumulated in the society by forty years of neoliberal policies. It is by linking the struggle for social justice and environmental justice in an anti-capitalist and anti-productivist perspective that it will have the greatest chance of succeeding. •

This article first published on the International Viewpoint website.

Daniel Tanuro is a certified agriculturalist and ecosocialist environmentalist, writes for La gauche, (the monthly of the LCR-SAP, Belgian section of the Fourth International). He is the author of Le moment Trump (Demopolis, 2018).