[Video at link here.]

Dan Edwards watched Fort McMurray, Alberta, turn into the insolvency capital of Canada from a brown brick warehouse on King Street, home to the Wood Buffalo Food Bank.

“You never know who’s going to walk through your door,” said Edwards, the food bank’s director. “Individuals that have degrees and education and skills—but the jobs just aren’t what they were.”

Once the booming heart of the country’s energy industry, the little city of 75,000 in northeastern Alberta has become a showcase for the debt troubles many Canadians are facing. Fat paychecks and generous overtime earlier this decade fueled big spending on customized pickups and million-dollar homes. With work drying up, the bill has come due.

Consumer insolvency filings in the Fort McMurray district climbed 39 per cent in 2018, the largest percentage increase in Canada, federal data show. Claims against property, the first step in the foreclosure process, surged almost tenfold over the past three years, according to court records. The city’s 90-day delinquency rate on non-mortgage loans climbed to 1.75 per cent in the second quarter, compared with 1.12 per cent nationally, according to Equifax Canada.

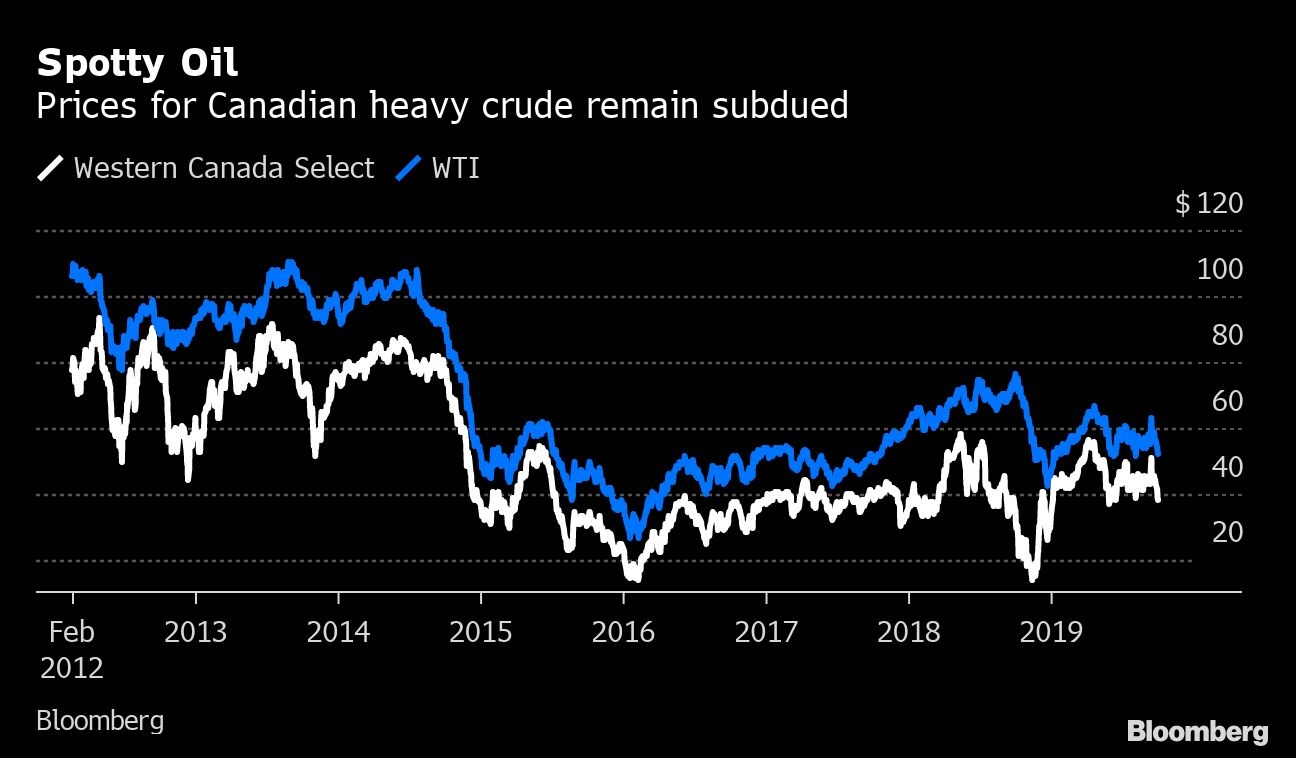

The five-year slump that’s cut oil prices in half since 2014 has been a driver in the bust. What piled on the pain was a crippling shortage of pipelines out of the McMurray Formation, a massive reserve of crude-laden oil sands. Plans for new lines have been squelched or stalled by court challenges from an array of opponents, including U.S. activists who view the oil sands as a “carbon bomb” that will one day unleash a climate catastrophe.

Stewardship of the energy industry has become a central issue of Canada’s federal election later this month. The Conservative Party has portrayed itself as a champion of the sector and pledges to remove regulations Prime Minister Justin Trudeau implemented. The Liberals, meanwhile, are trying to strike a balance between developing Alberta’s energy resources and making Canada a leader in combating climate change.

In May, after five years at Suncor Energy Inc.’s Fort Hills oil-sands mine, Steve Richardson was let go, like many others in the industry.

Richardson earned around six figures most years as a heavy equipment operator. For about 10 months, he commuted from Vancouver Island in British Columbia, with Suncor paying for most of his flights and putting him up in a camp near the work site. He’d dig trenches for 14 days, then go home for seven.

After the travel reimbursements stopped, he moved his family to a small town about a seven-hour drive from Fort Mac, so he could keep the job. Now he’s doing short-term work and making economies where he can, such as canceling his family’s cable subscription.

“I spend a lot of time wondering what the next job is going to be,” Richardson, 42, said. He’s thankful he resisted buying boats or taking vacations on credit, as many of his friends did. “I never got into all the toys. I’m kind of fortunate that way, that I didn’t have to sell everything off like some other people. I’ve seen a lot of that. It’s like a fire sale.”

The energy business has long been core to the local economy. Commercial production got off the ground in the 1940s, but the oil was always a devil to recover. It’s mired in a sludge that has to be tediously pumped out or strip-mined in open pits. Either way, the process is technologically challenging.

The potential, though, is staggering. With 165.4 billion barrels, these oil sands are the world’s third-largest proven reserve, trailing only those in Venezuela and Saudi Arabia. As oil prices were climbing from 2004 to 2014, the industry invested $210.1 billion, more than last year’s combined total capital spending by all of the companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Over those 10 years, oil-sands output more than doubled, to 2.2 million barrels a day. Canada shot up from the world’s eighth-largest oil-producing nation to the fifth-largest, overtaking Iran, Mexico and Norway.

It was a heady time.

Tax revenue and corporate sponsorships paid for a revamp of the Fort McMurray International Airport, improvements to schools, top-notch hockey facilities and a gleaming new recreation center, where Carrie Underwood was a recent headliner.

The city’s population doubled as workers crowded in from around the country, sending rents and home prices surging and prompting a cascade of typical boomtown challenges, from crazy traffic to crowded schools. Companies, desperate for labor, threw six-figure salaries at low-skill jobs and covered commuting costs for roughnecks and people from as far away as Canada’s Atlantic Coast. Median annual household incomes more than doubled from 2001 to 2011, to about $181,000.

Then oil prices tanked. The pipeline plans stalled. International giants, including Royal Dutch Shell Plc, ConocoPhillips and Total SA sold off their major oil-sands assets. Capital investments are on track to decline for a fifth straight year to an estimated $12 billion this year, about one-third of the 2014 level, according to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

Several operators—Suncor, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., Cenovus Energy Inc. and a few others—are still active and generally profitable. But they’ve managed that by cutting costs, including, of course, that of labour.

“People aren’t getting the overtime that they used to get, or they’re not getting any overtime at all,” said Sandra Landry, an insolvency trustee at MNP Ltd.

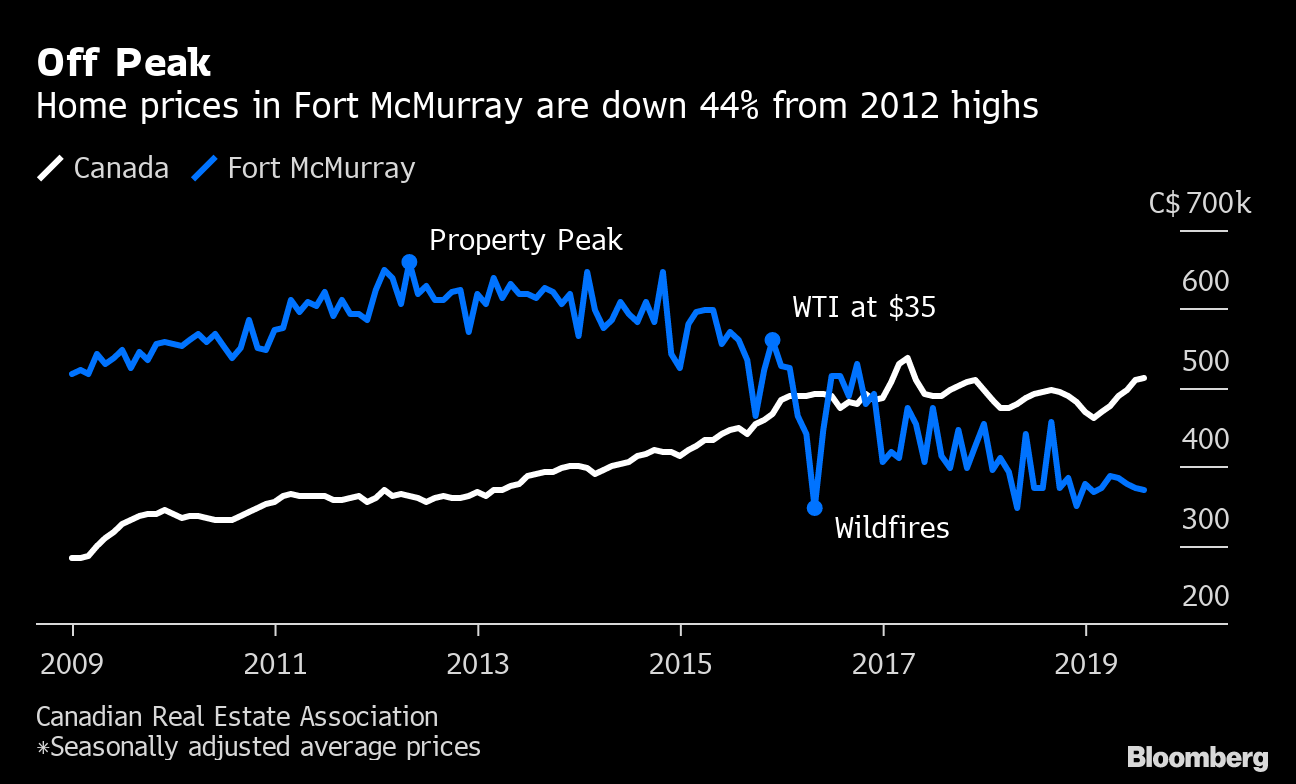

If things weren’t bad enough when oil bottomed around $26 a barrel in early 2016, the largest wildfire in recent history swept through the Fort Mac area that May. It forced the evacuation of more than 80,000 people, destroyed almost 2,000 homes and caused about $3.7 billion in insured losses, making it the country’s costliest natural disaster.

“The housing market is down, there’s the economic downturn and there’s still the recovery from the fire,” said Don Scott, mayor of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, which includes Fort McMurray. Home prices remain 44 per cent below the recent peak.

Sean O’Byrne moved to Fort Mac from Grande Prairie, Alberta, after the fire to open a branch of a friend’s siding business to repair damaged houses. That work dried up in November. Now he’s selling cars, making far less than the $1,000 a day he could rake in with the siding business; customers at the General Motors dealership are no longer trading in for new models every two years. He and his wife have cut back on travel and moved to a cheaper apartment closer to their children’s school, saving $900 in rent, he said while sipping coffee in a Tim Hortons doughnut shop facing a forested area, where charred trees stick out among new growth.

“People aren’t spending money like they used to,” he said.

They likely won’t be in the near future. There are only a few projects on the horizon that would create many new jobs. Teck Resources Ltd.’s proposed $20 billion Frontier mine is in the early stages of the regulatory-approval process. Imperial Oil Ltd., a subsidiary of Exxon Mobil Corp., has put its long-planned $2.6 billion Aspen mine on hold, waiting to see if the pipeline situation improves.

There aren’t many bets being laid that it will. More than a few folks would rather it not. Since the frenzy died down, traffic has returned to normal, in part because the oil money helped build a new bridge, over the Athabasca river. The unemployment rate, which skyrocketed to around 10 per cent in 2016, has settled down to 6.3 per cent, mostly a function of workers decamping for more promising prospects.

“That massive boom and gold-rush mentality that took place—I would rather not relive that,” said Alex Pourbaix, chief executive officer of Cenovus, adding the entire industry has learned the benefits of measured growth.

These days, the company will only consider expansion projects that will be profitable with the benchmark U.S. oil price at $45 a barrel, about $10 less than the current level. Some oil-sands projects undertaken a decade ago required $100 a barrel to break even.

John Hickey is also content with the slowdown. A mechanic who works on used oil-industry vehicles, he lost his house in the wildfire. Two years ago, a builder quoted him $500,000. The offers keep moving down, and he’s waiting for one to get to $200,000 or so before going ahead.

In the meantime, he’s sharing a one-bedroom condo with a friend, sleeping in a tent in the living room to give himself a bit of privacy. He still has work and has always lived within his means, a lesson for places like Fort Mac that can see the money go as quickly as it came, he said.

Too many, he said, “made a lifestyle based on an economy that wasn’t sustainable.”