Articles Menu

Mar. 14, 2023

|

Hello! I’m Lisa and I follow environmental policy for The Times. There was a big win for fossil fuels this week, so the newsletter team invited me in to talk about what Big Oil is thinking and what we might expect from the industry going forward. |

|

To sum it up, confidence is high in the oil and gas world. That’s very different from where we were just a couple of years ago and it has important implications for the global transition to cleaner energy. |

|

A huge decision on Alaska |

|

You might have read my articles over the past few days about the Willow project in Alaska. That’s an $8 billion plan to extract 600 million barrels of oil from the largest remaining expanse of wilderness in the United States. President Biden approved Willow on Monday, much to the displeasure of environmentalists. |

|

When he did, he also enacted some new protections designed to limit fallout in the drilling area, which lies about 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. They included a ban on offshore drilling in the Arctic Ocean and safeguards for some nearby wetlands. |

|

How did the oil industry react? In a sign of that newly restored swagger, rather than just taking the tremendous victory of Willow and laying low, executives generally made a point of criticizing the new environmental protections. |

|

“In the current energy crisis, the Biden administration should be focused on strengthening U.S. energy security and standing with the working families of Alaska by supporting the responsible development of federal lands and waters, not acting to restrict it,” said Frank Macchiarola, a senior vice president at the American Petroleum Institute, a trade organization. |

|

Even before the Willow decision, though, you could sense the industry’s growing optimism. I saw it for myself this month at CERAWeek, an annual energy conference in Houston. |

|

Backpedaling on promises |

|

Two years ago, as the Covid-19 pandemic drove down demand for oil and Biden took office promising to steer the country away from fossil fuels, the industry was on its heels. Leading companies were promising to reduce the carbon emissions that come from their products and that are heating the planet to dangerous levels. |

|

But that started to shift last year. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine scrambled global energy markets, spiked gas prices and led the Biden administration to plead with oil and gas producers to increase production to ease the pain at the pump during an election year. |

|

Now, after raking in record profits, several oil giants seem to be backtracking on promises they had made to reduce their contributions to global warming. |

|

Exxon, for example, has dropped a project to produce environmentally friendly fuels from algae, one of the company’s most publicized climate efforts. Shell pumped the brakes on its renewable energy spending, saying its investments in wind, solar and biofuels will stay flat after hitting a high in 2022. |

|

And BP, which announced three years ago that it would transform, stop looking for oil and gas in new areas and slash fossil fuel production, has watered down its ambitions. Last month, the company revised its plan to cut production by 40 percent by 2030, setting a new target of 25 percent. The company’s share price surged on the news. |

|

Bernard Looney, the BP chief executive, told the gathering in Houston that shareholders were “very pleased” by the retrenchment. “They like the fact that we could create value by investing in hydrocarbons,” or fossil fuels, he said. Mr. Looney did note that BP is investing $8 billion into new renewable projects, the same amount it is putting into oil and gas. |

|

“We can’t take our eye off the system which is energy security and energy affordability today,” Mr. Looney said. But he insisted “we’re all in on trying to make the transition work.” |

|

Jason Bordoff, dean of the Columbia University Climate School and a former senior energy official in the Obama administration, said it was clear that fossil fuel companies are feeling bullish about the future. “This is an industry that’s making a lot of money right now and is going to be for several years to come at least,” Bordoff told me when we met in Houston. “I think it is feeling good about the economic outlook. Energy security has re-emerged to the top of the agenda.” |

|

Even as many boasted about remaining investments in solar, hydrogen and technology to capture and store carbon dioxide, industry leaders reminded audiences at the conference that their primary job is pumping oil. |

|

“We saw in 2018, particularly with a lot of the climate emphasis, that people were pulling back from oil and gas,” Darren Woods, the chief executive of Exxon, said at one session. “We leaned in. We were heavily criticized for doing that at the time, but we recognized that, at some point, that supply was going to be needed.” |

|

What’s next? |

|

While the industry was opposed to the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark legislation passed last year that included $370 billion in incentives for clean energy development, oil and gas executives are eager for some of those technologies, like hydrogen as fuel and carbon capture technology, to become commercially viable. That means you can expect energy companies to try to cash in on some of those incentives programs. |

|

Carbon capture in particular, which would remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and lock it away in rocks, would guarantee a future for oil and gas without the worry that burning those products would continue to heat the planet. |

|

“The issue of how we best move toward a lower-carbon energy system is one that is getting reframed,” said Mike Wirth, the Chevron chief executive, who said that a “disorderly transition” to clean energy could be dangerous. |

|

“We have to be very careful about turning System A off prematurely and depending on a system that doesn’t yet exist and hasn’t been proven,” he said. (For the record: carbon capture itself has yet to be proven at scale.) |

|

I also sat down with John Kerry, Biden’s special envoy for climate change. Kerry said he saw some encouraging signals from companies, including the interest in carbon capture and hydrogen, but he said the industry as a whole was not making a serious enough effort to cut emissions and move away from fossil fuel development. |

|

“There is a need to make this transition as rapidly as we can,” Kerry said. “I think there’s a big question mark about what they’re really prepared to do.” |

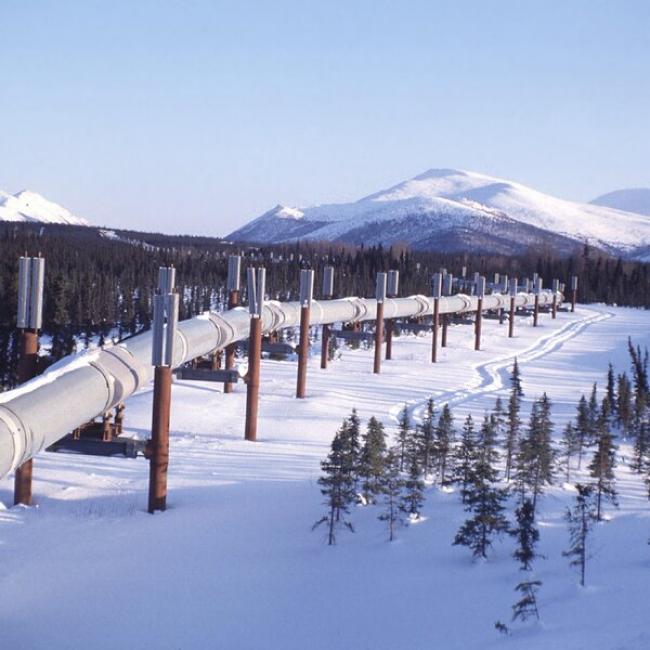

[Top photo: A section of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, which spans the state from north to south, near Valdez.BLM Photo/Alamy]