Articles Menu

Apr. 16, 2020

Daniel Steinbrook’s job at Whole Foods has changed completely as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. His store is mobbed. Many customers come in wearing masks. Steinbrook, who works at a Whole Foods in Cambridge, Massachusetts, hasn’t been given a mask by his employer and was told he couldn’t wear a scarf over his face for added protection.

“It’s been extremely stressful,” Steinbrook said. “And it’s grown increasingly stressful over time as the pandemic has advanced and the risks have gotten higher.”

On March 31, he and his fellow Whole Foods workers across the country went on strike, orchestrating a mass sick-out to protest what they say is a lack of protections for employees and customers alike. It’s the first national collective action ever staged by Whole Foods employees.

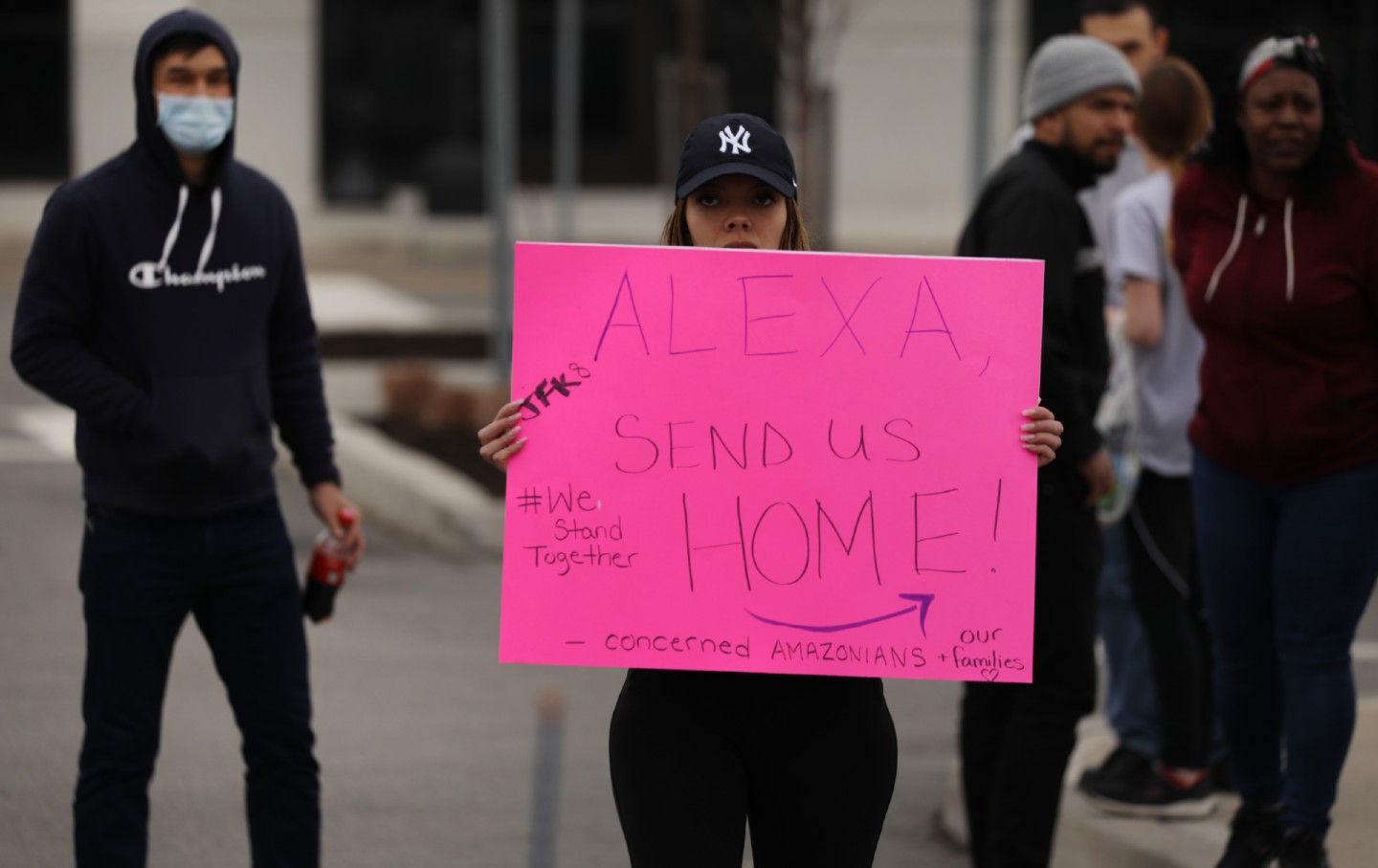

They are one of a number of groups of workers who have gone on strike in recent weeks. Amazon warehouse workers walked off the job in Detroit, Chicago, and New York City; in the latter, they’ve now staged two strikes in as many weeks over safety and pay concerns. Workers at fast-food restaurants such as McDonald’s, Burger King, KFC, Checkers, Domino’s, and Waffle House have gone on strike in California, Florida, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee. They’ve been joined by workers at companies where workers have never gone on strike before, such as Family Dollar, Food Lion, and Shell gas stations. Instacart shoppers held a national strike on March 30, refusing to accept orders. Workers for Shipt, Target’s same-day delivery service, organized a walkout on April 7. The unrest has even spread to bus drivers, poultry workers, and painters and construction workers.

The stakes are high. Many of these workers have been deemed essential as their employers stay open. But, striking workers say, their employers are not doing enough to protect their health and keep them financially afloat. Already, grocery workers have started to die from Covid-19.

This marked the first time that Steinbrook took part in workplace activism. “I’m not someone who ever gets involved in things like this,” he said. “I normally just shut up and do my job.”

Finding out that Whole Foods’s paid sick leave policy requires a positive Covid-19 test even though the company isn’t covering the costs of tests galvanized him. “It incentivizes employees to come into work sick,” he explained. And, he pointed out, Whole Foods’s policy runs counter to guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control.

So Whole Foods employees have issued a set of demands: paid leave for anyone who isolates or self-quarantines, health care for part-time and seasonal employees, company coverage of coronavirus testing and treatment for all workers, double hazard pay, new policies to facilitate social distancing in stores and ensure adequate sanitation, and an immediate shutdown of any store where an employee tests positive with pay for all of its employees.

The company did not respond to a request for comment. In response to the pandemic, it has increased hourly pay by $2 an hour.

Steinbrook doesn’t believe the company will make changes without pressure. It’s already ignoring the CDC recommendations, as well as a letter sent by 14 state attorneys general and the attorney general of Washington, D.C. urging the CEO of Amazon, which owns Whole Foods, and the CEO of Whole Foods Market to change its paid sick leave policy. Executives are “not listening to the government,” Steinbrook noted. “They’re not going to listen to me, just a random employee.” But, he hopes, they might listen to employees banding together.

“Since the entire nation is shut down…and grocery stores are one of the few places open, I think that they have a big responsibility for public health,” he said.

That sentiment—that so many employers are putting their employees in danger by flouting the recommendations of authority figures—is part of what has made this moment such a fertile one for labor activism according to Nelson Lichtenstein, distinguished professor of history at the University of California Santa Barbara. The current swell of strikes comes after two years of a huge uptick in worker unrest: more workers went on strike in 2018 than any time since 1986, and the numbers held steady last year. “People face crises with the ideas and traditions and impulses that have immediately gone before it,” Lichtenstein pointed out. It’s no coincidence that all of these workers have responded to this crisis with walkouts after two years of strikes by teachers, nurses, and Uber drivers—not to mention movements like Occupy Wall Street and the Fight for 15. “We have had a decade where these ideas are floating around,” he noted.

But something vital has shifted. “It’s not just that their [working] conditions are bad—that’s been in existence forever,” he said. Now these workers are being called heroes and told by society “they are part of a larger, important…vital functioning of society.” That makes it even more egregious when their employers then violate the “new set of social norms and moral structures set up by this crisis,” he said. “There demands [have been] legitimized by other people in authority and power and prestige.” Workers feel a sense of empowerment in their new, essential roles—which makes them even more outraged when their employers don’t live up to the moment and take steps to protect and compensate them adequately. “Those things come together and create an explosive situation,” he said. This moment “gives them a sense of moral righteousness.”

There’s another factor on workers’ side: All of these companies are in high demand right now. Grocery stores can barely keep shelves stocked. Customers are relying on deliveries from Amazon and Instacart so they don’t have to go outside. Workers “have the leverage here,” Lichtenstein said.

Mario Crippen can’t afford to stay away from his job at an Amazon warehouse in Detroit. He has a three-month-old and a six-year-old to provide for. At the same time, he’s terrified of bringing coronavirus home to his family. At least three of his coworkers have tested positive; employees in 64 Amazon warehouses and shipping facilities have now tested positive. When he arrives at work he goes straight to his station—the company is not doing any screening for Covid, he said—and waits to be given the one bleach wipe per worker to wipe down his entire station. The company has run out of masks for employees and has stationed employees by doors to squirt sanitizer into people’s hands in order to ration it.

Amazon’s current order volumes look like we’re in the midst of the winter holiday frenzy. “I feel like I’m on my last days when I walk in there,” he said. He was at work when he got a call from the company informing him that two of his coworkers had tested positive. “That made me so scared,” he said. “It made me think, ‘Do I already have it, what if I go home and give it to my family, what’s going to happen to them, who’s going to be the breadwinner for the family, who’s going to take care of them, how is my family going to pay for a funeral?’ All those thoughts running through my head.”

Amazon employees hold a protest and walkout over conditions at the company's Staten Island distribution facility. (Spencer Platt / Getty Images)

“I’d rather be a part [of the strike] than to lose my life for that job,” Crippen said. “A job can be replaced. But your life cannot be.”

On the morning of March 12, Jordan Backman, who lives in Issaquah, Washington, woke up planning to fulfill shopping orders for Instacart like she does every weekday, but “I just felt off,” she said. By the evening she had a constant, painful cough; then she developed a fever. A few days later her son developed the same symptoms. There was a string of days when she was so sick she could barely get out of bed. The only way she could have been exposed, she said, is working for Instacart.

When she called the hospital, she was told to go into a 14-day quarantine, so she stopped working. When she finally recovered, she figured she would be able to get pay from Instacart for the time that she was sick, given that the company has said it will offer 14 days of paid leave to anyone “who is diagnosed with COVID-19 or placed in individual mandatory isolation or quarantine, as directed by a local, state, or public health authority.” But the company denied her because it said she wasn’t told to quarantine by a public health official and because her test came back negative, even though there is a high rate of false negatives.

“I was really excited to get back to work after not being able to work for two weeks,” she said. But her frustration over the company’s refusal to grant her paid leave pushed her to take part in a national strike on March 30. Organizers say thousands of other Instacart workers joined her, some of whom are refusing to do shopping trips until their demands are met. Backman is also on strike indefinitely. “I’m not working until Instacart decides to pay me,” she said. She also wants the company to commit to at least $5 of hazard pay per order.

“We have been consistently, proactively communicating with the shopper community to ensure they have the support they need,” Instacart said in an e-mail. “We’ve made a number of significant enhancements to our products and offerings over the last few weeks that demonstrate Instacart’s unwavering commitment to prioritizing the health and safety of the entire Instacart community.” That includes providing disinfecting supplies and safety kits for its workers in the wake of the strike, sick pay for all part-time employees, and bonuses ranging from $25 to $200 depending on how many hours were worked. But so far, Instacart has not budged on its requirements for using paid sick leave or increasing hazard pay.

At a Food Lion grocery store in North Carolina, Nyreese Cole can barely keep the shelves stocked. People are buying so much that the store has put limits on certain items, such as meat and toilet paper. And yet the company isn’t giving employees masks and gloves. Cole has bought his own latex gloves. “The only thing that’s available to help is sanitizer at the front door and washing my hands in the bathroom,” he said.

“I know I’m risking myself every day I do go to work,” he said. But he needs all of the hours he can get at work so that he can pay his bills; he’s even been calling to see if he can get extra shifts. “It might sound crazy, but I feel like I don’t have a choice,” he said. “At the end of the day, rent is going to keep coming.”

He currently makes $10.50 an hour as a stocker, and the company has said it will give employees an extra dollar as hazard pay. But he wants hazard pay of at least $15 an hour. He also thinks the company should guarantee paid sick leave. So he joined fast food and retail workers to go on strike across the Raleigh-Durham area on March 27 with, he says, at least one other Food Lion coworker.

Food Lion disputes that any strike took place at its store. “We did not have any widespread absentees,” Matt Harakal, manager of external communications, said in an e-mail. “As a result of the coronavirus outbreak, we have implemented pandemic guidelines, including modified attendance policies, enhanced compensation and other key benefits. We are monitoring this fluid situation, and continue to follow guidance from local, state and national health authorities including the CDC.” He also said the company recently ordered face masks for employees.

Bettie Douglass is also seeking more hours even though she’s worried that her job has left her exposed. She was working a full-time schedule at McDonald’s in Missouri, but when the coronavirus hit and demand dropped, the company reduced her hours to 20 per week. She’s worried that her utilities will be cut off come May 1. Her refrigerator broke and she doesn’t have the money to fix it, but without it it’s hard for her to stock up on food for her family.

So she’s still going to work at McDonald’s, even though she’s 62, and even though the company hasn’t given any of them masks. “All we were told was use the sanitizer and wash hands frequently,” she said. “I have to take a chance everyday because I can’t afford not to go to work.”

As soon as she heard there was a strike brewing, “I knew I was going to do it,” she said. “Because if you don’t stand for something, you don’t stand for anything.” She walked off the job along with more than 100 other fast-food employees in both St. Louis and Tampa, Florida on March 31.

She’s been with McDonald’s for 14 years and has never gotten a raise. “We don’t have any type of retirement, we don’t have any type of benefits, we don’t have any type of sick pay,” she noted. Unlike many of the workers who’ve recently gotten active, Douglass has gone on strike before, with the Fight for 15. “I’m going to continue to do it until we get some better benefits, until they take us into consideration and take us serious,” she added.

“Our highest priority is to protect the health and well-being of our people,” McDonald’s owner and operator Nicole Enearu said in an e-mail, in a response to a request for comment. She said she has made “an ample supply” of gloves available to employees and is asking sick employees to stay home.

Some of these strikes have been orchestrated by Fight for 15 organizers, who have led larger and larger walkouts among fast-food workers and other low-wage employees for several years, demanding higher pay and the right to form a union, as well as newer groups, such as Working Washington, which has been organizing Instacart and other gig workers. But others have sprung up more organically. Whole Foods employees are not unionized, and the company has a history of aggressive union busting. There, the sick-out emerged from “online organizing of random employees who are concerned,” Steinbrook noted. “It was probably obvious before, but it’s definitely obvious now: the need for employee organizing to protect themselves and stand up for themselves.” These strikes could therefore extend beyond the end of the current crisis, whenever it might subside.

Striking workers have notched a few victories. Instacart said it will provide free health and safety kits to workers. Lawmakers have taken notice; Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Ro Khanna unveiled an “Essential Workers Bill of Rights” on Monday that would grant grocery store, food service, warehouse, delivery, and other workers health and safety protections, premium pay, and paid sick and medical leave.

For now, the wave of strikes shows no sign of cresting. Amazon workers in New York and Chicago have staged other one-day walkouts since the one Crippen joined in Detroit. Fast-food strikes have spread to California. After workers at a pizzeria in Chicago learned that a coworker had tested positive, they all walked out of the job on April 11. And the employees who already took part may do so again. Despite Steinbrook’s prior reluctance to join in workplace activism, he’s prepared to do more. “If these things are not changed, if these demands in the petition are not addressed immediately, there absolutely will be more mass actions,” he promised. Whole Foods workers are already planning another sick out for May 1. Steinbrook and his coworkers also hope that their action “will have a cascading effect on other grocery stores and other retail chains.”

As the crisis continues to unfold, a general strike—one that extends across industries and, indeed, possibly engulfs the whole country—“is not inconceivable,” Lichtenstein said. If unrest spreads from not just frontline employees but throughout entire companies, those companies would have to shut down until workers’ demands are met. There are budding signs of such solidarity: white-collar Amazon employees sent an internal e-mail in support of the warehouse workers who have gone on strike and protested publicly about their working conditions; in response, Amazon fired two of them on Friday. It would be similar to entire school systems being shut down to support teachers going on strike in 2018.