Articles Menu

Aug. 2021

Critical Minerals on Stolen Land

Neskantaga First Nation Chief Wayne Moonias was tired as he made the two-hour flight from his remote, roadless Indigenous community on the headwaters of the Attawapiskat River to Thunder Bay, Ontario. Moonias was attending a private meeting between Matawa Chiefs and the Australian mining giant Wyloo. Wyloo had just completed the takeover of Canadian junior mining company Noront and was holding an introductory meeting to promote its ambitious plans: by mining clean energy minerals on the homelands of Neskantaga, it would create a new mining economy for the Matawa communities and a green energy future that could help save the planet.2

Chief Moonias was tired of living in a continuous social emergency. Neskantaga is a remote Anishnaabe community with no safe drinking water, overcrowded housing infested with mold, and erratic health and education services that are far below the standard of non-Indigenous towns and cities in northern Ontario.3 The living conditions in Neskantaga are no better and no worse than the majority of the roadless Indigenous communities of Ontario’s Far North. These communities are among the poorest in the world, ranked between 63rd and 78th in the United Nations Human Development Index.4 “Broken treaty,” “unmarked graves,” “racism,” “land back,” and “cultural genocide” are more than words on the banners at protests; they describe the lived experience of the Neskantaga people.

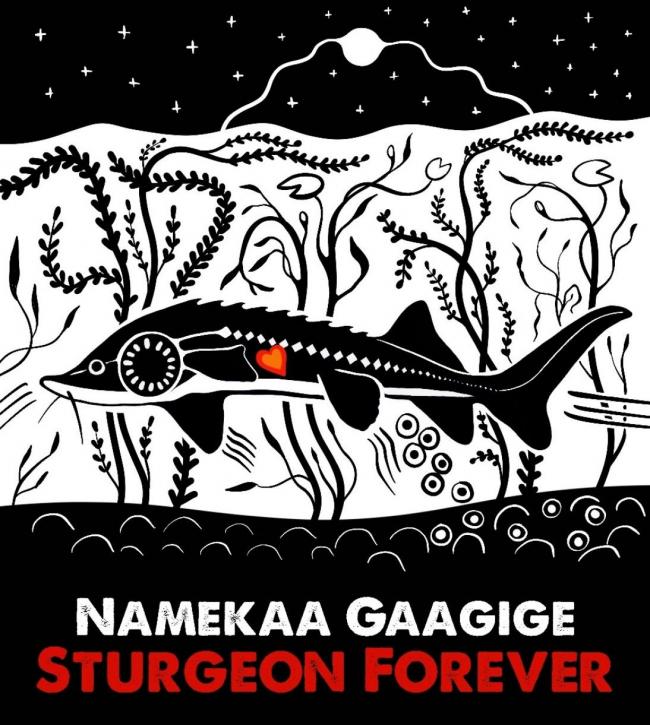

For Neskantaga, the people are the land and the land are the people. The Attawapiskat River is hundreds of miles long. Since time immemorial, Neskantaga members have relied upon the Attawapiskat watershed to practice their way of life: hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering food and medicinal plants, and holding ceremonies. From the summer until winter, they harvest sturgeon, whitefish, pickerel, pike, speckled trout, burbot, and other fish. They hunt moose and occasionally take woodland caribou, and each spring and fall they hunt geese, ducks, and other animals. The water and people of the Attawapiskat River watershed have been braided together through stories and rooted in the birth places, burial grounds, cabins, and fishing and hunting sites where food was and continues to be shared since time out of mind.5

Wyloo, the private mining investment vehicle of Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest, is calling its Ontario mining project the “Future Metals Hub.” This ambitious scheme involves building new roads and bridges on the Attawapiskat watershed, a net-zero-emissions nickel mine, battery production, a ferrochrome refinery, and a jobs program for the Matawa First Nations.6 To realize the Wyloo vision will require the completion of six environmental assessments currently underway, approvals of Federal and Provincial Ministers, and about $5 billion of public and private capital.7

Scientists have noted that Canadian peatland, which includes the Neskantaga homeland, is the second largest carbon sink left on the planet.8 The James Bay lowlands which house the Attawapiskat watershed are vital to Earth’s carbon regulation, holding more than thirty-five billion tons of carbon in soils and peat.9 The Anishinaabe knowledge keepers of James Bay call this area Bakidanaamowahkiin or “the Breathing Lands,” a vital sink that keeps carbon sealed in the muskeg and out of the atmosphere, benefiting the entire planet and future generations.10

In the years leading up to the meeting with Wyloo, the world was not good in the Attawapiskat watershed, homeland of Neskantaga. The community of 400 had been locked down for much of the previous two years, and movement in and out of the community was restricted to essential services with strict requirements regarding self-isolation for travelers. The social isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic had profoundly disrupted the face-to-face world of the community, and too many community members had died untimely deaths. Neskantaga, in a land of lakes, rivers and wetlands, has the dubious honor of being on Canada’s longest community boil-water advisory. For twenty-seven years there has been no clean drinking water in Neskantaga, and during the pandemic the water system failed completely, requiring the entire community to evacuate for sixty-one days.11

When Chief Moonias took the microphone at the meeting, his message to the Wyloo negotiators and his fellow Chiefs was blunt: Wyloo’s mining claims are on stolen lands, and there will be no shovels in the ground without Neskantaga’s consent.

For Neskantaga, the phrase “stolen lands” was a judgment on the broken promises of James Bay Treaty No. 9. In the remembering of Neskantaga elders and knowledge holders, when Ontario and Canada made treaty in 1905, the Crown’s goal was simple: move Indigenous people off their homelands and confine them to reserve lands in order to make way for mining, forestry, dams, and other so-called “developments.”12 This was, in David Harvey’s apt phrase: accumulation by dispossession.

But the ancestors of the Indigenous signatories had a different understanding of the treaty. They remember that they never gave up their land and their jurisdiction on the land. For the Indigenous knowledge rememberers, the land belongs to the Creator, not the Crown. In their memories, the land is not about ownership, it is about relationships: relationships of sharing and peace.13

Hop on a Bulldozer

After miners hit nickel in 2007 while drilling on lands the Matawa and Mushkegowuk claimed as their own, Neskantaga and the eight other First Nations in the Matawa Tribal Council began a series of on-again, off-again negotiations with the Province of Ontario, Canada and a changing cast of mining companies that has lasted to this day.14 The so-called Ring of Fire mining district, covering an area of 1,237,998 acres, was located in a roadless wetland more than 180 miles from the highway network and the transcontinental railhead.15 Early estimates put the cost of the road and infrastructure to develop the mining district at a daunting $1.74 billion. While the mining industry and their lobbyists promoted the district as a $60-billion opportunity that would deliver one-hundred years of mining, more than 5,000 jobs, and approximately $3 billion in federal tax revenues,16 skeptics doubted their optimistic projections of the value and volume of the mineral deposits.17

For more than a decade, the stock market stood with the pessimists. The shares of the mining company that controlled the majority of the Ring of Fire mining claims languished around twenty cents a share. However, by 2022, with the Russia-Ukraine war disrupting Russian nickel exports, rising anti-China protectionism, and a new narrative about minerals critical for the development of clean energy and electric vehicles, mining majors Wyloo and BHP were drawn into a bidding war for the Ring of Fire mineral deposits. Wyloo emerged on top, and junior mining company Noront walked away with more than $600 million.18 Neskantaga received nothing.

In March 2014, a Liberal Party provincial government began negotiating a regional framework agreement with the Matawa Nations on infrastructure, closing the social gap, revenue sharing, and environmental protection. Three years later, the negotiations reached an impasse when the First Nations demanded real decision-making powers on their homelands.19 The Conservative government that followed in 2018 shut down the Matawa negotiating table, with the Premier brazenly threatening to hop on a bulldozer himself to begin building the road to the mining district.20

Green Energy, New Protectionism, and National Security

On first reading, this may seem to be a story about a small, uniquely vulnerable Indigenous community in Northern Ontario standing up to a transnational Australian mining bully and its state partners who are hell-bent on making a road and a mine, no matter what the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples and Neskantaga’s own Indigenous laws say. The demands, threats, and offers of the campaign write themselves—support Neskantaga’s right to say no, save the “Breathing Lands,” stop the Ring of Fire, and help save the planet.

But for Wyloo, Ontario, and the Canadian state, the nickel, chromite, platinum, and copper in the “Breathing Lands” of the Neskantaga homeland are now critical minerals urgently needed to build the batteries for the transition to a low-carbon, cleaner energy future. After years of ignoring the province’s demand that Canada match Ontario’s $1 billion infrastructure commitment to the Ring of Fire, in the 2022 federal budget, Canada announced a $1.5 billion fund to build infrastructure that prioritizes mining remote deposits of critical minerals.21

If the Ring of Fire goes forward, clean-energy minerals would become Canada’s answer to the planetary damage created by Alberta’s dirty oil, and the “Breathing Lands” and Neskantaga’s way of life would be sacrificed for what are supposed to be global climate and sustainability goals, but which in reality come down to extractivist growth and capitalist development.

Frustrated by the failure of the regional negotiations, in March of 2020 two of the nine Matawa First Nations abandoned the Matawa campaign for new decision-making institutions in their homelands and became provincially funded proponents of what they now term “an indigenous-led environmental assessment” process to plan the roads to the Ring of Fire mining district.22 For the Marten Falls and Webequie First Nations, mining was a way to all-weather community roads, community well-being, and the economic security that Canada and Treaty No. 9 had promised back in 1905 but had never delivered.

With two of their members now acting as road proponents, a majority of the Matawa Tribal Council incorporated a for-profit development corporation to work with Canada’s largest private construction company, a provincial electrical utility, and Canada’s oldest conservative lobby on a green-energy battery initiative. An organization that for decades was a Treaty Council that acted by consensus and advocated for treaty and Aboriginal rights was now pursuing a system of one-member–one-vote majority rule and tasked with entering into partnerships with major corporations to build much-needed houses and water treatment plants, along with an EV battery company.23

In the middle of the pandemic, while Neskantaga was dealing with lockdowns, Canada’s longest boil-water advisory, and community evacuations, Ontario started the clock on a complex set of six environmental assessments for the roads that would unlock the development of the Ring of Fire project in the Neskantaga homeland. The province buried the community in a blizzard of complex technical documents and imposed impossible process deadlines in the regulatory maze of technical environmental assessment, ignoring Neskantaga’s laws and protocols for community decision-making, and the ongoing social emergency the community was facing.24

Under the new auspices of clean energy, critical minerals, and continental energy security, a Conservative provincial and a Liberal federal government abandoned past “antagonisms” and now united behind a plan to invest in a new Ring of Fire mining economy “for” the Matawa First Nations. In January, 2020, Canada and the US announced the Canada-US Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration aimed at countering China’s mineral dominance and securing supply chains for critical minerals used in strategic industries such as defense, aerospace, and communications.25 Under the terms of the agreement, the two levels of government will jointly subsidize the road project and infrastructure costs for Wyloo. The state will supply resources to the economic machine of Wyloo and create legitimacy by giving the appearance of industry and government working for the good of Indigenous people. The failed historical James Bay Treaty No. 9 is replaced by a new Indigenous social contract.

The New Indigenous Social Contract26

The roots of the new social contract for Indigenous people go back to a wave of Indigenous protest, blockades, and legal victories in the 2000s. Facing a cycle of Indigenous contention, the courts made First Nation consultation a necessary requirement for any major resource development in Canada. Capital followed the movements, struggles, and aspirations of the First Nations and translated the legal uncertainty around the meaning of "consultation" into distribution-centered bargaining, agreements with resource corporations, and the sharing of revenues with provinces.27

Under the new social contract, the state’s role is to help pay for mining roads and other infrastructure, train First Nation workers, and share a small portion of state mining revenues with the First Nations. The mining corporation's role is to set ambitious Indigenous employment targets, train and hire Indigenous workers, buy from First Nation suppliers, and minimize environmental damage with the oversight of First Nation monitors. Corporate revenues are often shared with First Nation community partners, and First Nations are increasingly equity partners in dams, pipelines, forest companies, liquefied natural gas plants, and even the tar sands project.28

The more sophisticated sectors of the Canadian political and business elite had long recognized that a new deal with First Nations would be essential to developing the new frontiers for resource extraction and containing an Indigenous rebellion.

The First Nation social contract met extractive capital’s need to stabilize the business environment by expanding demand and markets, both domestic and foreign. The state met the legal obligation for Indigenous consultation and foreclosed the political question of free, prior, and informed consent. First Nations would develop their own sources of revenue from extractivism to close the gap on Indigenous housing, education, and health care.

Taking a page out of the new corporate collaboration agenda that saw Canadian foundation-funded environmental organizations make peace with forest companies,29 the new First Nation social contract embraces those Indigenous goals most consistent with capitalist extractivism and precludes development paths that give Indigenous Nations real power to determine the scale, place, and forms of production on their homelands.

Staying with the Trouble

Neskantaga realize that, once the roads to the Ring of Fire mining district are built, they will lose any leverage to protect the Breathing Lands, their way of life, and the possibility of real First Nation jurisdiction on the land. The community is beginning preparations to defend the land. A lawsuit has been launched to challenge the environmental assessments of the road to the mining district.30 In accordance with Treaty No. 9, First Nations on the James Bay who share the stewardship of the Breathing Lands with Neskantaga are demanding that the Ring of Fire development be suspended and that an Indigenous-led regional planning process with real First Nation decision-making power be negotiated with the federal and provincial governments.31

But beyond lawsuits and alliances, Neskantaga are asking us to imagine a radical change in the semiotics of minerals. Suddenly, driving an electric car in Germany could mean the destruction of a world-class carbon sink, the extinction of the Attawapiskat sturgeon, and complicity with an ongoing cultural genocide. A battery or an electric vehicle could become an emotionally charged object that would stand for the morbid crisis ridden form of social life created by the relentless drive of capital for profits that destroys both ecosystems and the ways of life of indigenous peoples.

The resistance of Neskantaga forces us to reconsider our notions of purity when promoting cleaner energy and compels us to ask uncomfortable questions. Are the minerals in the Neskantaga homelands the right minerals for the right product? Is nickel the wrong mineral for the right product, or are electric vehicles just simply the wrong product? Is the sacrifice of the way of life of one Indigenous community a suitable price to pay for the minerals needed for the cleaner energy transition and to fund the new Indigenous social contract that other First Nations in the region have already agreed to? If the Ring of Fire is stopped, will dirty mining simply migrate from northern Ontario to Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or Mongolia? Should we leave the minerals in the Breathing Lands in the ground and reduce mineral production altogether as part of the road to degrowth?

Neskantaga plan to “stay with the trouble,”32 avoiding the defeatist despair that comes from being a small, remote Indigenous community standing in the way of capital and the state’s definition of clean energy, and avoiding as well the naive hope that one lawsuit can stop the road and mines. They know that the odds of stopping Wyloo from lighting the mining fuse that will set off a “Breathing Lands” carbon bomb is a long-shot, but they will fight for their right to imagine and determine the way we will see them, their way of life, the Attawapiskat River, and the “Breathing Lands” in the future.

David Peerla is a long time advisor to the Neskantaga First Nation and writes from his home in Thunder Bay. A founding editor of the journal Capitalism Nature Socialism, David was the producer on a recent CBC radio documentary on the Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug and the Fight for Indigenous Resource Sovereignty.

https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2056424515864

https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-391-superior-morning/clip/1593832...

1 A version of this essay appeared in Science For The People, Volume 25, no. 2

Bleeding Earth, Autumn 2022

2Heather Kitching, “Australian Owner of Major Ring of Fire Deposits Brings Big Promises, Controversial Reputation,” CBC News, May 25, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/wyloo-metals-ontario-ring-of-fire-andrew-forrest-stake-1.6443170.

3Dayna Nadine Scott et al., “Implementing a Regional, Indigenous-Led and Sustainability Informed Impact Assessment in Ontario’s Ring of Fire,” Osgoode Digital Commons (April 2020): 2807, https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works/2807/.

4Shari Narine, “Political Parties Must Address Indigenous Issues During Federal Election, Say AFN Candidates,” Toronto Star, June 22, 2021, https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2021/06/22/political-parties-must-address-indigenous-issues-during-federal-election-say-afn-candidates.html.

5Scott et al., “Implementing a Regional, Indigenous-Led and Sustainability Informed Impact Assessment.”

6“Wyloo Metals commits to world-class Future Metals Hub in Ontario,” GlobeNewswire, May 31, 2021, https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2021/05/31/2238742/0/en/Wyloo-Metals-commits-to-world-class-Future-Metals-Hub-in-Ontario.html.

7The $5 billion estimate is arrived at by combining the $3 billion mine and refinery and the $2 billion road and infrastructure estimates reported on by the Globe and Mail. See Niall McGee and Jeff Gray, “The Road to Nowhere: Claims Ontario’s Ring of Fire Is Worth $60-Billion Are Nonsense,” Globe and Mail, Oct 25, 2019, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-the-road-to-nowhere-why-everything-youve-heard-about-the-ring-of/.

8Camile Sothe et al., “Large Soil Carbon Storage in Terrestrial Ecosystems of Canada,” Global Biogeochemical Cycles 36, no. 2 (2022): e2021GB007213, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GB007213.

9James Wilt, “The Battle for the ‘Breathing Lands’: Ontario’s Ring of Fire and the Fate of Its Carbon-Rich Peatlands,” The Narwhal, July 11, 2020, https://thenarwhal.ca/ring-of-fire-ontario-peatlands-carbon-climate/.

10Allan Lissner, “The Breathing Lands,” Alternatives Journal, February 28, 2013, https://www.alternativesjournal.ca/community/web-exclusive-the-breathing-lands/.

11Olivia Stefanovich, “Neskantaga Evacuees Relieved to Be Home, but Distrust about Water Quality Lingers,” CBC News, December 21, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/neskantaga-2020-repatriation-water-emergency-1.5849643; Heather Kitching, “Neskantaga First Nation Surpasses 10,000 Days under a Drinking Water Advisory,” CBC News, June 20, 2022, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/neskantaga-water-advisory-anniversary-1.6494213; Chief Wayne Moonias Affidavit, March 4, 2022.

12John S. Long, Treaty No. 9: Making the Agreement to Share the Land in Far Northern Ontario in 1905 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010).

13John S. Long, “Treaty No. 9: DC Scott’s Accidental Gift,” (paper presented at the Forty-Third Algonquian Conference, Ann Arbor, Michigan, October 2011), 179, https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/download/2284/2058/.

14Jon Thompson, “The Tories Are Dissolving the Ring of Fire Agreement. So What Comes Next?,” TVO Today, September 3, 2019, https://www.tvo.org/article/the-tories-are-dissolving-the-ring-of-fire-agreement-so-what-comes-next.

15 “Ontario’s Ring of Fire,” Government of Ontario, accessed August 1, 2022, https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontarios-ring-fire.

16Jed Chong, Resource Development in Canada: A Case Study on the Ring of Fire (Ottawa: Library of Parliament, 2014), https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/bdp-lop/bp/2014-17-eng.pdf.

17McGee and Gray, “The Road to Nowhere.”

18 Niall McGee, “Wyloo Tops BHP’s Bid for Noront as Tussle for Ring of Fire Operator Intensifies,” Globe and Mail, December 13, 2021, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/industry-news/energy-and-resources/article-wyloo-tops-bhps-bid-for-ring-of-fire-junior-noront/.

19Matt Prokopchuk, “Ontario Government Ends Ring of Fire Regional Agreement with Matawa First Nations,” CBC News, August 27, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/regional-framework-ends-1.5261377.

20“Progressive Conservatives Outline Plan for Northern Ontario,”

CBC Sudbury, March 16, 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/doug-ford-northern-ontario-1.4579311.

21Anja Karadeglija, “Critical Minerals Strategy Needed before Federal Government Starts Spending Budgeted $3.8B: Experts,” National Post, April 13, 2022, https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/critical-minerals-strategy-needed-before-federal-government-starts-spending-budgeted-3-8-billion-experts.

22Webequie First Nation and Marten Falls First Nation, “Environmental Assessment Planning Begins on Proposed Northern Road Link,” Cision, May 3, 2021, https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/environmental-assessment-planning-begins-on-proposed-northern-road-link-896385428.html; Matthew Parizot, “Ontario and Matawa Region First Nations Sign Agreement for Ring of Fire Road,” CIM Magazine, March 3, 2020, https://magazine.cim.org/en/news/2020/ontario-and-matawa-region-first-nations-sign-agreement-for-ring-of-fire-road-en/.

23 Heather Kitching, “Matawa Partnering with the Business Sector to Solve First Nations Infrastructure Deficit,” CBC News, March 9, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/matawa-infrastructure-partnership-1.5488751; The Matawa battery initiative is referenced in: Matawa Chiefs Council, 2020/2021 Chiefs Council Report (Thunder Bay, September, 2021), http://www.matawa.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Matawa_2021_Chiefs-Council-Report.pdf.

24Logan Turner, “Neskantaga First Nation Taking Ontario to Court over ‘Inadequate’ Consultation on Ring of Fire,” CBC News, November 3, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/neskantaga-legal-action-ring-of-fire-1.6266870.

25Natural Resources Canada, “Canada and U.S. Finalize Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration,” Government of Canada, January 9, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/natural-resources-canada/news/2020/01/canada-and-us-finalize-joint-action-plan-on-critical-minerals-collaboration.html.

26 This section is based on an opinion piece I published with Shiri Pasternak on the CBC website in May of 2014. See https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/first-nations-social-contracts-how-to-contain-an-aboriginal-rebellion-1.2654595

27Bruce McIvor, Standoff: Why Reconciliation Fails Indigenous People and How to Fix It, (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2021).

28Ken Coates, Sharing the Wealth: How Resource Revenue Agreements Can Honour Treaties, Improve Communities, and Facilitate Canadian Development (Ottawa: MacDonald Laurier Institute, January, 2015), https://www.macdonaldlaurier.ca/files/pdf/MLIresourcerevenuesharingweb.pdf.

29Merran Smith, Art Sterritt, and Patrick Armstrong, From Conflict to Collaboration: The Story of the Great Bear Rainforest (Coast Funds, 2007), https://coastfunds.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/StoryoftheGBR.pdf.

30Julian Falconer, “Neskantaga First Nation Goes to Court Over Ontario’s Flawed Consultations on Ring of Fire Road,” CBC News, November 31, 2021, https://falconers.ca/neskantaga-first-nation-goes-to-court-over-ontarios-flawed-consultations-on-ring-of-fire-road/.

31“3 northern Ontario First Nations declare moratorium on Ring of Fire development,” CBC News, April 7, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/ring-of-fire-moratorium-1.5977066.

32 Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

[Top image: Image by Christi Belcourt.]