Articles Menu

July 5, 2023

The Pathways Alliance plastered Toronto streetcars and Vancouver billboards with optimistic messages about its plan to slash pollution and help Canada meet its climate goals. Behind the scenes, the coalition of fossil fuel producers struck a different tone.

A collection of internal government documents obtained by The Narwhal show how six major oil companies lobbied the federal government to weaken and delay plans to place a cap on heat-trapping pollution from the oil and gas sector.

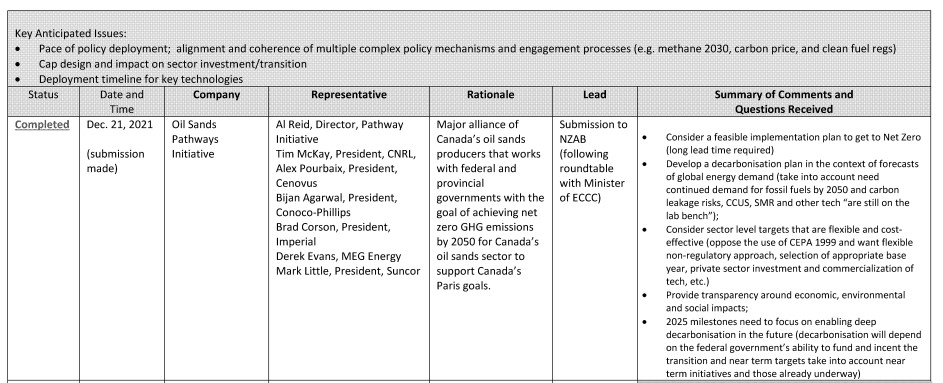

The Narwhal pieced together the extent of industry lobbying after reviewing six separate responses to access to information requests, totalling 69 pages. These documents show that, as early as December 2021, oil companies in the Pathways Alliance — Suncor, ExxonMobil affiliate Imperial Oil, Canadian Natural Resources, ConocoPhillips Canada, MEG Energy and Cenovus — were urging the government to consider “flexible and cost-effective” rules and give the industry a “long lead time” to prepare before they mitigate how they are contributing to the global climate crisis.

The comments were part of the government’s early, informal consultations on the emissions cap that would signal the start of months of meetings between senior government officials and Pathways executives touching on the cap’s design.

The documents — released by Natural Resources Canada — also show the lobbyists pressured the government to take a “non-regulatory approach” on slashing carbon pollution, one that could make it easier for industry and provincial governments to challenge or delay federal climate action through the courts.

The documents include numerous examples of how oil lobbyists may be misleading the public.

Despite telling Canadians its net-zero plan was “in motion” and it was “making clear strides,” the documents show the Alliance downplayed progress in private discussions with the government. The lobbyists said technologies needed to fight the climate crisis are “still on the lab bench,” or in other words still in development. And while these same companies have reported making record profits, they claim they don’t have enough money to implement climate-friendly solutions.

“This is further evidence that the oil industry is aggressively lobbying for more government subsidies, loopholes and lower ambition,” said assistant professor Amy Janzwood at McGill University’s Bieler School of the Environment, who studies fossil fuel production and sustainable energy and reviewed the Alliance’s comments at The Narwhal’s request.

The Pathways Alliance did not respond to The Narwhal’s requests for comment. The industry group’s president said in June that the group has “enough in our toolkit today, with existing game-day-ready technologies, that can get us to net zero” and that the oilsands companies don’t need to rely on “some future breakthrough technology that doesn’t exist today.”

Capping the carbon pollution that fossil fuel companies spew into the atmosphere is necessary because rising emissions from the oil and gas sector, and from gas-powered transportation, have almost entirely offset declines in other economic sectors’ emissions projections for 2030, according to the independent Canadian Climate Institute.

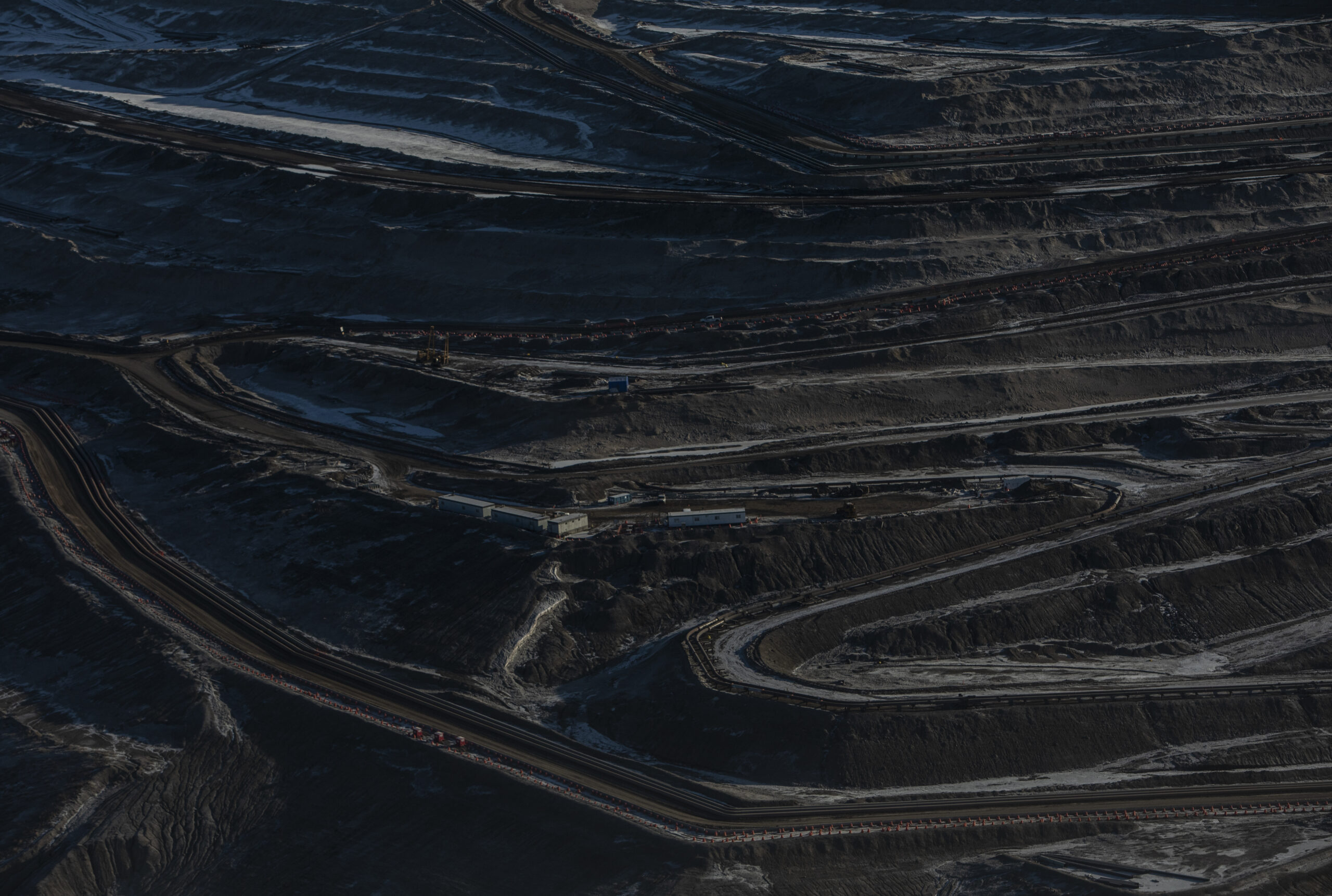

Emissions from the oilsands in particular have climbed by over 460 per cent since 1990 to reach 85 million tonnes in 2021. This trend is threatening to ruin Canada’s chances of meeting its emissions reduction targets, which is part of a global commitment to curbing the catastrophic consequences of the climate crisis, from extreme heat waves, wildfires and floods to deteriorating air quality, poverty, disease, ecosystem destruction and the deaths of tens of thousands of people.

Last summer, after the government proposed that the oil and gas sector limit its emissions in line with projections in Canada’s climate plan, the Pathways Alliance went public with concerns about the emissions cap, calling the trajectory “not realistic” and suggesting it could force energy companies to cut their oil production instead.

But briefing notes and internal government summaries of industry consultations have revealed the Alliance was lobbying against a more stringent version of an emissions cap in December 2021, and warning the government about the risk of production cuts in February 2022.

The Alliance made the comments to Canada’s Net-Zero Advisory Body, which provides advice to Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault, after holding a roundtable with the minister, according to Natural Resources Canada’s internal summary of the comments.

The remarks were part of informal discussions the government held on the emissions cap before formally launching consultations in 2022. The government “kicked off” these early consultations by holding the meeting with the Pathways Alliance on Dec. 21, 2021, according to a briefing note prepared for Natural Resources Canada’s deputy minister at the time, John Hannaford.

All of this occurred before the government had released two key documents — its March 2022 climate plan, and its July 2022 emissions cap discussion paper which Pathways would later finger as the basis for its complaints about the cap.

“They’re clearly pursuing slower, weaker emissions caps as part of what I see as a more general trend towards climate delay in the sector, and even globally,” said Chris Russill, an associate professor and academic director at Re.Climate, an environmental communications centre at Carleton University.

In addition to requesting an interview, The Narwhal also emailed a list of questions to the Pathways Alliance and all its member companies concerning this report, as well as asked questions to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, which counts five of the six Pathways firms as its own members. None responded.

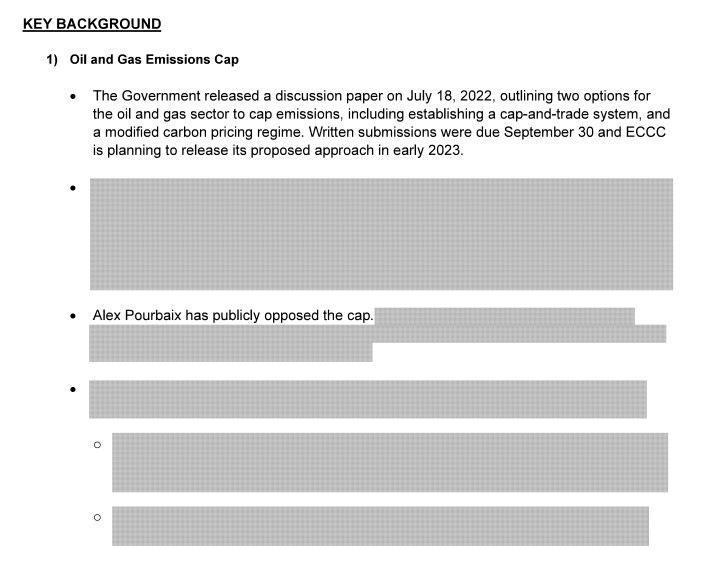

The federal government’s July 2022 discussion paper outlined two possible ways Canada could establish an oil and gas emissions cap in law.

One option is using the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. Under that law, the government would create new regulations to form a “cap-and-trade” system to specify an allowable amount of emissions from the oil and gas sector over a given period of time. The government would then auction off, or give away, permits to polluters for each tonne of emissions that was allowed for the period, and polluters would then submit one permit for each tonne of emissions they are responsible for.

To use an oversimplified example, if there were 100 tonnes of emissions allowed for a given period, the government would distribute 100 permits — one for each tonne. Companies have to turn in permits for each tonne of carbon they emit, so across the industry, no more than 100 tonnes of emissions can be generated.

The other option offered was to modify the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, which sets minimum national standards for a price on pollution. The law would have to be amended through legislation to establish a new carbon price and emissions standards specifically for the oil and gas sector.

Pathways made no mention of the carbon pricing system as an alternative in its early comments on the emissions cap, but the documents reveal how the Alliance took issue with the Canadian Environmental Protection Act being used as a basis for establishing the policy in law.

Pathways would “oppose the use of CEPA 1999,” the government wrote in its summary of the group’s comments in December 2021, using the acronym for the law and the year the bill was last amended. (The law was amended again this summer.)

Several organizations have said using the environmental protection law to establish an emissions cap makes more sense. The Pembina Institute, an Alberta-based energy think-tank, said that option would be quicker and simpler, since it wouldn’t require new legislation to be passed. Meanwhile, if the government used the carbon pricing law method, it would likely spell delays as the provinces and territories would have to be consulted, the think-tank said.

Canadian environmental organization Environmental Defence argued the cap-and-trade model “does provide more certainty and is the stronger option out of the two,” as long as “strong rules are put in place to ensure ambitious emissions reductions from within the oil and gas sector.”

University of Calgary law professor Martin Olszynski, who researches environmental and natural resources policy, has argued the federal government has constitutional jurisdiction to enact a cap under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act.

Olszynski told The Narwhal using the environmental protection law could mean the emissions cap is less likely to crumble under legal challenges. In 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed the constitutionality of the carbon-pricing law based on the fact that it established “minimum national standards, without targeting specific sectors, and that this flexibility was key,” he said.

If the government used the carbon pricing law to establish the emissions cap, Olszynski noted it “would need to be amended to go after specific sectors, and that may throw its constitutionality in doubt.”

“So if Pathways prefers this route, it’s probably because they would challenge it in court before the ink was dry,” he said.

The government had intended on releasing its decision on which method to use by “early 2023,” the records show, but as of early July, Ottawa had not announced those details.

Guilbeault’s spokesperson Kaitlin Power said the government is still deliberating on the emissions cap.

“We actively engaged with stakeholders and are in the process of reviewing the data and advancing internal design decisions. Once we are in a position to share more details we will,” she said.

The Pathways Alliance formed in the summer of 2021. It was initially founded by five oilsands producers — Suncor, Imperial Oil, Cenovus, Canadian Natural Resources and MEG Energy. At the time, they claimed they would achieve “net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from oilsands operations by 2050,” in order to “help Canada meet its climate goals, including its Paris Agreement commitments and 2050 net-zero aspirations.” In November 2021, ConocoPhillips Canada joined the group as the sixth member.

The Alliance’s lobbying on the emissions cap would happen just six weeks after the group had fully formed. The Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had won the September 2021 federal election on a platform that promised to “cap and cut emissions from oil and gas.”

The details of the Alliance’s feedback, recorded in a Natural Resources Canada chart released to The Narwhal, shows how the government had asked the Alliance for its “high-level preliminary thinking” on the design of the cap. At the time, the government was also consulting with provinces and territories, other oil and gas industry groups and major companies, the details of which were censored in the released records.

The Pathways Alliance told the government it should “consider a feasible implementation plan to get to net zero” that would allow for a “long lead time” for the companies to prepare, according to a summary of the group’s comments in the departmental chart.

The Alliance asked the government to consider “sector level targets that are flexible and cost-effective” for the emissions cap, and that it wanted a “flexible, non-regulatory approach” to emissions cap rules.

Pathways also said the emissions cap’s first milestone in 2025 should be primarily about having the foundations in place for “deep decarbonization” to happen sometime “in the future.”

Flexibility is a common refrain in fossil fuel lobbying and submissions to the Canadian federal government, said Sofia Basheer, a senior analyst at the London-based energy think-tank InfluenceMap, who tracks oil and gas industry influence.

The group’s February report examining the Canadian oil and gas industry found the Pathways Alliance “appears to be getting increasing traction in Canadian climate policy debates,” by emphasizing support for emissions reductions from its operations and support for carbon capture technology, while also advocating in favour of “a long-term role for oil.”

The organization said it could not identify any evidence of the Alliance putting forward a position on the role for oil that would align with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s recommendations.

“It seems like these are attempts to weaken the ambition of the [emissions cap] policy,” Basheer said. “They do not really talk about what flexibility, or compliance flexibility, means.”

Basheer said the comments from Pathways demonstrate how oil companies are misleading the public about being able to produce carbon-free oil. That was the basis for a Greenpeace Canada-led complaint about the group’s marketing practices that Canada’s Competition Bureau is now investigating, she said.

“When you advertise to the public ‘We can produce net-zero oil,’ they are not telling the whole story,” Basheer said.

The Alliance’s plans rely on technology that hasn’t yet been fully developed, or budgeted for, it told the government.

The Pathways Alliance has said it will capture carbon dioxide emissions from oilsands facilities and build a new pipeline to transport the captured carbon to underground storage areas. It also has plans to electrify some of its operations with non-emitting electricity by using small modular nuclear reactors.

The group asked the government to “take into account” how its decarbonization plan relies on carbon capture and nuclear technologies that “are still on the lab bench,” according to its December 2021 comments on the emissions cap.

“Decarbonisation will depend on the federal government’s ability to fund and incent the transition,” added the Alliance.

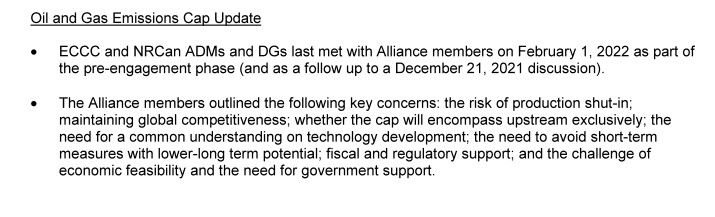

The government’s early consultations on the emissions cap were followed by another round on Feb. 1, 2022, when senior public servants in Natural Resources Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada heard from Pathways Alliance members for a second time, according to an April 2022 briefing note prepared for one of the departmental deputy ministers.

During those consultations the oilpatch group expressed concerns over “the challenge of economic feasibility” surrounding the emissions cap, and highlighted the “need for government support” as well as “fiscal and regulatory support.”

Pathways also flagged “the need to avoid short-term measures with lower-long-term potential.” It’s unclear what this means, and Pathways did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions seeking clarity.

Several witnesses who appeared at the House of Commons environment committee’s study on fossil fuel subsidies said public funding of carbon capture technology risks promoting future oil and gas extraction at a time when scientists say fossil fuel production must be scaled back.

As a result, the committee recommended the government “ensure that all its policies and measures, including those related to support for the fossil fuel sector, are consistent with — and efficiently achieve — the country’s 2030 emissions reduction goals and its 2050 net-zero emissions goals.”

While opinions may vary about the oil and gas sector’s ability and desire to decarbonize, there was an “elephant in the room” when it comes to the Pathways plan, said Russill — the fact that the oil it produces will still generate emissions when it’s burned.

Carbon capture in the oil and gas sector “does nothing to reduce the approximately 80 per cent of emissions that come after production, from burning fossil fuels in cars and homes, for energy generation,” the committee noted.

Canada is the fourth largest oil producer in the world, but about four-fifths of the oil it produces is exported — so the country avoids responsibility for all the carbon pollution created when its exported oil is used in foreign countries.

“The Pathways Alliance is primarily focused on their own operational net zero,” Basheer said.

“They want to produce oil, but remove any emissions associated with their oil and gas production. But at the same time, they don’t care about what happens when their oil is burned, which is where our primary chunk of emissions comes from.”

During the government’s February 2022 consultations on the emissions cap, the Pathways Alliance outlined a number of “key concerns,” the briefing note prepared for the Natural Resources Canada deputy minister stated. At the top of the list was “the risk of production shut-in.”

The idea that placing a cap on oil and gas emissions could lead, inadvertently or not, to limiting the amount of oil that would be produced in Canada, has become a main message of the Pathways Alliance in the months since it first lobbied the government on the topic.

The theory works this way: if the government makes a rule limiting the pollution fossil fuel companies emit, but the companies have not yet implemented the technology to capture that pollution or make less of it, the only other way to comply with the new rule would be to produce less oil and gas in the first place.

In August 2022, for example, the Alliance penned an editorial suggesting an oil and gas sector emissions cut in line with Canada’s 2030 climate plan was “simply unworkable given current technology, construction and regulatory requirements.”

“Impractical timeframes” for emissions targets, the editorial continued, could drive away investment, “reducing production in Canada and increasing production and emissions in other countries.”

But some economists say the Canadian industry’s future depends more on the price of oil in world energy markets, and how fast Canada and other countries implement climate policies and transition away from fossil fuels.

In the International Energy Agency’s net zero by 2050 scenario, where much of the world implements strong climate policies, global crude oil consumption would plummet from 94 million barrels per day to 22 million barrels per day in 2050, as countries become oversupplied with petroleum products no one wants anymore.

That oversupply would translate into much lower crude oil prices, the agency said — dropping from around US$75 per barrel today to US$35 per barrel by 2030, and US$24 per barrel by 2050 (all figures in 2021 dollars).

Those low prices, in turn, will be the “dominant factor” in a steady decline of oil production in the Canadian oilsands after 2030, according to a recent major report by the Canada Energy Regulator.

“The impact that the price of global commodities have on our analysis is very important,” Jean-Denis Charlebois, the regulator’s chief economist, told The Narwhal.

Everything from fuel to maintenance, royalties and climate policies like carbon pricing will drive up operating costs for producers, to the point where they start to outweigh revenues. At that point, facilities will start to close, the regulator said.

“Oilsands facilities that have the highest operating costs begin shutting down early in the 2030s. As oil prices continue to drop, more and more facilities shut down production, and only the lowest-cost projects are still producing in 2050,” the report stated.

The regulator found that oilsands oil production would fall to 0.58 million barrels per day in 2050, or 83 per cent lower than in 2022. Canadian crude oil production as a whole would drop 76 per cent from 2022 levels by 2050, or from five million barrels per day to 1.2 million barrels per day.

Nevertheless, the fear of an oil “production cap” being the result of a domestic Canadian emissions cap became a theme in internal government conversations with Pathways representatives, documents show.

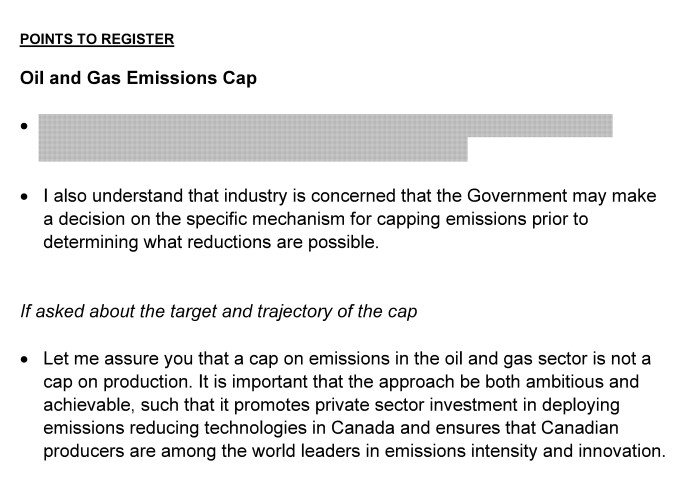

During a June 7, 2022 meeting between Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson and the Canadian Fuels Association’s board of directors, for example, the minister’s briefing note included the talking point that “the intent of the cap is not to curtail production unless it is driven by declines in global demand.”

Four months later, when Cenovus, one of the Pathways Alliance companies, requested a meeting with Hannaford, the deputy minister from Natural Resources Canada, he was instructed to tell the company the following: “Let me assure you that a cap on emissions in the oil and gas sector is not a cap on production.”

While the federal government’s plan for capping emissions from oil and gas hasn’t yet been released, Basheer says there is a narrative in political circles about how it’s possible to have net zero oil. But she says this narrative doesn’t align with science.

“It shows that the lobbying was actually working.”

[Top photo: Documents show that as early as December 2021, oil companies in the Pathways Alliance, such as Suncor which operates this open pit oilsands mine near Fort McMurray, Alta., were lobbying the government to consider “flexible and cost-effective” rules for its emissions cap. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal]