Articles Menu

Dec. 15, 2024

In February 8, 2024, Earth reached a new milestone. The European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service reported that mean temperature in the previous 12 months had been more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. As the Progressive International (2024) commented, “Just nine short years ago, the world’s governments agreed in Paris that they would limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees. ‘1.5 to stay alive’ was the mantra. They failed in record time.”

In fact, the World Meteorological Organization’s State of Global Climate 2023, issued in March 2024, reports a plethora of records broken, even smashed, for greenhouse gas levels, ocean heat and acidification, surface temperatures, sea level rise, glacier retreat, and Antarctic Sea ice cover (World Meteorological Organization, 2024). These ‘records’ are broken at our peril, and indeed, the human dimensions of climate change are also undeniable. As the report observes, in 2023 “heatwaves, floods, droughts, wildfires, and intense tropical cyclones wreaked havoc on every continent and caused huge socioeconomic losses” (World Meteorological Organization, 2024:iii).

The consequences were particularly devastating for vulnerable populations, as “extreme climate conditions exacerbated humanitarian crises, with millions experiencing acute food insecurity and hundreds of thousands displaced from their homes” (World Meteorological Organization, 2024). It is hardly surprising that nearly 80 percent of the world’s leading climate scientists, when polled in the spring of 2024, foresaw a global temperature increase of at least 2.5 degrees Celsius by end of century. The vast majority of the most knowledgeable people on our planet “expect climate havoc to unfold in the coming decades” (Carrington 2024).

In 2018, a team of earth scientists introduced the term “Hothouse Earth,” in a widely cited article. They noted a rapid advance toward planetary thresholds at which “intrinsic bio-geophysical feedbacks in the Earth System … could become the dominant processes controlling the system’s trajectory” (Steffen et al. 2018:8254). These thresholds are called ‘tipping points’, beyond which climate change accelerates and becomes irreversible, in a cascade of positive feedback. The feedback processes include permafrost thawing, which releases methane (a greenhouse gas 84 times more impactful than CO2) and loss of polar ice sheets, which is not only elevating sea levels but weakening the albedo effect.1 As the planet warms, increased atmospheric methane and shrinking polar ice caps, triggered by global heating, amplify global heating.

There are other feedback loops. Climate chaos already underway (drought, wildfires) contributes to the die-back of tropical and boreal forests – turning ecosystems that have fixed carbon for millennia into grasslands and carbon bombs. Meanwhile, increasing volumes of atmospheric carbon precipitate as acid rain, reducing the oceans’ capacity to absorb carbon, and further heating the hothouse.2 Steffen et al noted that “Hothouse Earth is likely to be uncontrollable and dangerous to many … and it poses severe risks for health, economies, political stability … and ultimately, the habitability of the planet for human” (2018:8257). The challenge for humanity is to create “a ‘Stabilized Earth’ pathway that steers the Earth System away from its current trajectory toward the threshold beyond which is Hothouse Earth” (2018:8254).

The situation has been described as climate crisis, climate breakdown, climate emergency but, most ominously, as ecocide. In the scholarly literature, ‘ecocide’ emerged as a term in 1970 (Weisberg 1970) but was rarely invoked in the titles of academic articles and books until recent years.3 In his eponymously titled book, David Whyte defined ecocide as “the deliberate destruction of our natural environment” (2020:2), and pointed his finger directly at the profit-driven corporations that “are wrecking our world” (2020).

Stop Ecocide International, a movement organization campaigning to make ecocide an international crime, defines the term as “the mass damage and destruction of the natural living world,” literally “killing one’s home” (Stop Ecocide n.d.). Ecocide does not mean the end of nature, which is indifferent to any particular species, including ours. Nor is the prospect of ecocide a death sentence for all of humanity. Just as genocide – a term painfully familiar to us from contemporary Palestine – does not mean the annihilation of an entire ethnic group, ecocide implies the destruction of the conditions for a decent life for vast numbers of people. The growing numbers of climate refugees from regions that are already becoming uninhabitable – whether from sea level rise or desertification – confirm that ecocide is already upon us, in its earliest stage.

Ecocide is very much about the Earth’s prospects of supporting a large population of humans, but other species are already in sharp decline. Drawing on the most recent figures from the Living Planet Index,4 Patrick Greenfield (2022) notes that between 1970 and 2018 “wildlife populations have plunged by an average of 69%”; “the abundance of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles is falling fast, as populations of sea lions, sharks, frogs and salmon collapse.” Indeed, the climate crisis is entirely entangled with the Sixth Extinction, the cumulative decline of living systems – and of biodiversity – as forests are cleared to make room for cattle grazing, reducing biodiversity, impairing the Earth’s ‘lungs’ from fixing atmospheric carbon and increasing carbon emissions. Elizabeth Kolbert writes, in her Pulitzer Prize winning The Sixth Extinction:

“Having freed ourselves from the constraints of evolution, humans nevertheless remain dependent on the earth’s biological and geochemical systems. By disrupting these systems – cutting down tropical forests, altering the composition of the atmosphere, acidifying the oceans – we’re putting our own survival in danger.” (2014:267)

Although the Sixth Extinction looms in the background, this book is laser-focussed on the single most urgent ecological and existential challenge of our time: the climate crisis, its human causes, and the possibilities for refusing this cardinal element of ecocide.

The climate crisis is a natural phenomenon, driven by human activities (which, as I will explain in Chapter 1, are also natural phenomena). This has led many earth scientists to argue that the planet has crossed into a new epoch, the Anthropocene – that of the ‘geology of mankind’ – (Crutzen 2002), “beginning around 1950, representing the emergence of human-industrialized society as the primary factor in Earth System change” (Foster 2024:249). Critical social scientists, however, have noted that this term can be misleading. It fails to identify the specific human agents, operating within social structures, who are the primary drivers of the crisis. Andreas Malm (2016:391) suggests, “this is the geology not of mankind, but of capital accumulation.”

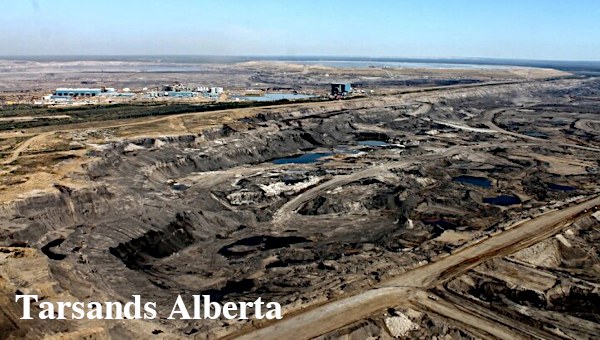

Certainly, the corporations that dominate the fossil fuel sector, and their predecessor firms, are the major culprits. In 2014, Richard Heede published an article documenting that between 1751 (before the invention of the steam engine) and 2010 the 90 biggest emitters – the ‘carbon majors’ – were responsible for 63% of cumulative worldwide emissions of greenhouse gases, with half of all emissions having been released since 1986. In the seven years following the 2015 Paris climate accord, the carbon majors increased their emissions; indeed 80% of global emissions from 2016 through 2022 “can be traced to just 57 corporate and state producing entities,” demonstrating “the outsized influence of a small group of producers that are increasing production” (InfluenceMap 2024:4, 26). Their investment decisions have directly caused the climate crisis, and continue to exacerbate it. The CEOs of these fossil-fuel producers could fit into a couple of school buses.

But the carbon majors are enabled by other actors and institutions. At the Corporate Mapping Project, a community-university research and public engagement project I co-directed from 2015 to 2023 (Carroll and Daub 2015; Carroll 2021), we mapped the various connections between the fossil-fuel sector and the economic, political, and cultural organizations that enable and legitimate its activities, focussing on the case of Canada, a major fossil-fuel producer. In Chapter 4, I reflect on some of our findings, which reveal a “regime of obstruction” that enables and protects the revenue streams and fixed-capital investments of fossil-fuel corporations and blocks meaningful climate action. The key actors in this regime include the banks and institutional investors that finance the industry, the captured regulators that green-light new investments, the government ministries in regular dialogue with industry lobbyists, and a range of organizations that legitimate the industry, from think tanks, industry groups, and business councils to corporate and astro-turf media and business schools.

This book focusses on these centres of economic, political, and cultural power. I analyze how their actions have driven the climate crisis, and why the ruling economic and political bloc, based in the advanced capitalist west, or global North, is incapable of steering humanity to a safe destination. Ecocide, however, is not inevitable. In recent decades, many initiatives have appeared in resistance and opposition to ecocidal practices. These include:

However, in the dominant institutions, including the annual Convention of the Parties (COP) that governs the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, corporate interests predominate, fettering the transformations that are obviously necessary. At COP 28, held in Dubai in December 2023, a record number of fossil fuel lobbyists (2,456 in all) outnumbered all national delegations but those of the host and host-designate. Dwarfing all official Indigenous representatives 7-to-1, those lobbyists found ready allies among the many fossil-fuel employees embedded in the national delegations of France, Italy, and other Northern countries (Corporate Europe Observatory 2023). Not surprisingly, COP 28, like all previous COPs,

“failed to agree on the need to phase out fossil fuels and to set a deadline for doing so. Instead, the final document suggests that states may – with no obligations – ‘draw down’ fossil fuel production. The demands from over 120 countries to completely eliminate new fossil fuel production were ignored.” (Progressive International, 2023)

The chasm between the urgency of serious climate action, understood by many, and the stasis of climate policy at global and national levels is palpable. Why this stasis, and what is to be done?

This book addresses these questions, in two parts. The first develops a critical perspective on fossil capitalism and climate breakdown, drawing primarily on the historical materialist framework first introduced by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. This framework directs our attention toward a ‘trifecta of power’ at the centre of capitalism as a way of life, illuminated via three core concepts. Capitalist accumulation, the economic aspect, is driven by the private profit motive toward endless growth and increasing inequities. Imperialism, the geo-political-economic aspect, entails the domination of the global South by advanced capitalist states as they strip the land of resources and super-exploit cheap labour. Finally, hegemony, the cultural and political aspect, organizes popular consent to the capitalist way of life, particularly in the global North.

In Chapter 1, I unpack that trifecta, and apply it in recounting the century-and-a-half epoch from the Industrial Revolution to the close of World War Two, during which fossil capitalism was fully established. Chapter 2 takes up the post-war era – the ‘golden years’ of economic prosperity, consumer capitalism and class compromise, from the mid-1940s into the 1970s, during which the Great Acceleration took shape, exponentially increasing carbon emissions and trending toward ecological overshoot.5 The final chapter in Part 1 brings us up to date. Powered by fossil fuels, capital has subjected the world to its predatory logic, eventuating in today’s deep civilizational crisis. In the 1980s and 1990s, the economic crisis of the 1970s was resolved through neoliberal policies of deregulation, privatization and austerity, as capital became more globalized and financialized. Although the global financial meltdown of 2008 discredited neoliberalism, no alternative has gained favour in the centres political-economic power. As climate breakdown becomes increasingly visible, and as a diverse array of movements for climate justice and sanity intensify hegemonic struggle, the neoliberal zombie stumbles toward the precipice.

The book’s second part appraises solutions to the climate crisis that have been proposed from various quarters. In these chapters I examine how proposed remedies square with our core analytical concepts of accumulation, imperialism and hegemony. This engagement with alternatives begins in Chapter 4 with a critique of the ‘false solutions’ comprising Climate Capitalism: attempts to regulate fossil capital via market mechanisms or to create techno-fixes, as in changing the energy source without addressing the socio-ecological relations at the heart of the crisis. The rejection of these approaches, which remain within the logic of accumulation, imperialism and bourgeois hegemony, leads to the final two chapters. Chapter 5 explores three alternatives that move us in the right direction, yet fail to provide the comprehensive approach that the civilizational and climate crisis actually demands. These projects – the Green New Deal, Degrowth, and Buen Vivir – each contain currents that could converge upon a refusal of ecocide.

The challenge lies in pulling these social forces into a coherent hegemonic project with a mass base. Chapter 6 takes up this challenge. I argue for a democratic eco-socialism that breaks decisively from both fossil capitalism and Climate Capitalism. A capacious eco-socialist project directly confronts the trifecta of power that is at the heart of ecological degradation and social injustice. It is our best bet, against lengthening odds, in refusing ecocide. •

This is an excerpt from William K. Carroll Refusing Ecocide: From Fossil Capitalism to a Liveable World, (London: Routledge, 2025).

Bill Carroll established the Interdisciplinary Program in Social Justice Studies at the University of Victoria in 2008 and served as its director from 2008 to 2012. His writings can be found at onlineacademiccommunity.uvic.ca/wcarroll.