Articles Menu

May 3, 2021

Canadian Dimension recently ran two important contributions to the discussion of basic income. In one, an excerpt from a new book on the subject, Jamie Swift and Elaine Power seek to show how the experience of COVID and the provision of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) prove their argument for basic income. In the other piece, NDP MP Leah Gazan makes a heartfelt case for the adoption of this policy in Canada. Both articles offer criticisms of left opponents of basic income that I think need to be responded to.

The Gazan article offers by far the sharpest challenge to those on the left who question whether basic income will help, rather than hinder, efforts to fight poverty and achieve greater equality. Its very title, “Who Controls the Basic Income Narrative?” sets the tone. Gazan goes beyond simply disagreeing with the arguments advanced by left critics of basic income and questions the validity of raising objections at all. As she puts it:

Some progressive critics of basic income advance arguments rooted in privilege, with an intent to control the narrative of the oppressed, the poor, the neglected, the forgotten, and the invisible. They encourage intellectual discussions about revolutions to overthrow systems of oppression while allowing piecemeal approaches for addressing poverty to continue. This self-righteous debate is borne on the backs of Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC), who have to continue to risk our bodies fighting on the frontlines for minimum human rights.

As someone who can be counted among those who have opposed basic income from the left, I’m included in Gazan’s line of fire. “Even the criticism of neoliberalism is borne on the backs of the poor,” she writes. “John Clarke has referred to the neoliberal trap of basic income as an ‘ongoing project to create an ever more elastic and precarious workforce… basic income leads to a situation where a portion of the wage bill is now covered by general tax revenues.’”

I confess that I do think this is a little harsh but I recognize that Gazan is approaching this whole issue from a position of deep conviction and entirely justifiable outrage that cuts a lot deeper than a disagreement over a matter of social policy. Everything she says about colonialism, racism and the impacts of poverty is searingly true. I also want to stress that the case she makes for basic income is obviously the result of considerable research and study and she puts forward a very serious argument. However, I do think she’s wrong to characterize left criticisms of basic income in the way she does.

In this period of hardship and uncertainty, there are strong hopes that basic income might make a difference, and many who live in poverty, including Indigenous people and people of colour, would share Gazan’s perspective. At the same time, there are others struggling with poverty who take a very different view. I could draw on lots of examples but Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC) in the United Kingdom is worth singling out as an organization that has developed the most clear cut and well reasoned opposition to basic income even as its members have faced extremes of austerity and social exclusion.

These days, basic income supporters include not a few of the representatives of the corporate elites that Gazan, very correctly, points a finger at. And to be blunt, Elon Musk, Pierre Poilievre and the Canadian Chamber of Commerce are probably in a stronger position to control the basic income narrative than people like me. Obviously, such voices of wealth and power have very different aims and intentions from those of Leah Gazan. That brings us to the main failing of those who advocate for a progressive basic income. They don’t consider adequately the economic, social and political context in which they are floating their proposals. Quite frankly, Motion 46 that Gazan put before the House of Commons is not likely to resemble any basic income system that might be legislated into existence. I feel it necessary to point out the prevailing forces that would be at play in such a situation, and here the question of why an organization like the Canadian Chamber of Commerce supports basic income is worth pondering.

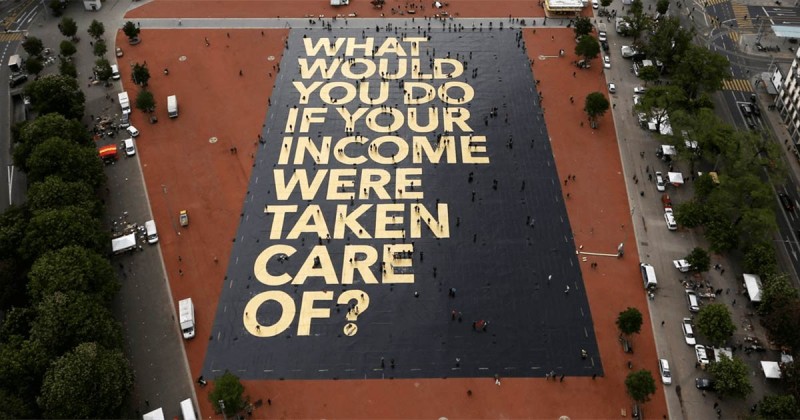

A giant poster covers part of the Plaine de Plainpalais square in Geneva while the country was considering the introduction of an unconditional basic income for all. Photo by Denis Balibouse.

The Swift and Power article also takes aim at left critics of basic income and on the very point that I have just made. It suggests that “Elements of the left oppose Basic Income because their ideological bête noire, Milton Friedman, had supported a minimalist version that would allow for the abolition of public provision.” It’s entirely fair to suggest that an idea shouldn’t be rejected simply because some reprehensible types latch onto it. However, in this case, the question to be answered is whether progressive hopes can triumph in the face of the harsh realities that Friedman did so much to usher in. In that regard, I’d like to set out some of the reasons why left criticism of basic income is neither abstract nor meaningless.

Historically, income support has always been deliberately and decidedly minimal. Governments concluded that, if utter social abandonment wasn’t an option, often because of the risk of popular resistance, then social provision would be reluctantly delivered in as inadequate a form as possible. The capitalist job market rests on economic coercion and the provision of even a barely sufficient income via any other means but wage labour threatens that power. The neoliberal decades have seen the degrading of income support systems so as to drive people into low wage precarious work. Access to a secure income outside of the job market has been severely restricted, with single parent benefits being eliminated and payments to injured workers and disabled people reduced and rendered less secure.

There are no grounds, therefore, to assume that if a basic income were to be introduced, it would have some virtually magical quality that would ensure its adequacy. On the contrary, in a liberal capitalist context, a basic income would be subject to the same pressures for the same reasons as existing income support systems. Employers would be just as hostile to a basic income that meets peoples’ needs as they are to decent unemployment insurance or social assistance payments. The relative adequacy of the CERB, paid out during the economic shutdown caused by the pandemic, is not the new benchmark that Swift and Power believe it to be. Under conditions of public health emergency and enforced shutdown, the state had to take exceptional measures to prevent social dislocation and disruption and a vast loss of revenue for businesses. This was the logic underlying the CERB. Indeed, Trudeau made the same point in an interview with the Financial Times. “That’s not a measure we can automatically continue in a post-pandemic world,” a starkly candid statement by Trudeau’s standards.

As I’ve argued previously, however, it is not just that basic income would fail to deliver on adequate income support and eliminating poverty. It’s that a huge extension of the cash payment would reinforce the commodification of social provision in dangerous ways. Gazan, Swift and Power clearly reject Friedman’s minimalist route and Gazan’s motion specifically calls for “wrap around” public services. However, there is no real explanation in either case of how we could prevent a real and actual basic income system from replacing, rather than augmenting, existing elements of the social infrastructure given that this is always the prime objective of right-wing models.

Gazan also maintains that “Basic income would give workers leverage.” No doubt, if everyone automatically received an income that enabled them to live perfectly well, the working class would have at its disposal a strike fund, provided by the state, and its bargaining power would be hugely enhanced. However, if a much more likely meagre cash benefit became a key source of income for the great bulk of low-wage workers, this would have the opposite effect. The basic income would serve as a subsidy to employers, paid for out of the taxes of slightly higher-waged workers. The need to seek low-wage work would be maintained but little pressure would exist to increase wages or raise the minimum wage.

A break with neoliberal austerity is currently underway, with the Biden administration leading the pack and the Trudeau government moving cautiously in the same direction. Its scale and duration are as yet unclear but, even if we take the promise of a new Keynesian golden age with a pinch of salt, this is a vital time for workers and communities to fight for major gains. There is no doubt that struggles around income support are part of this. Unemployment insurance must adequately meet the needs of workers, including those presently dumped onto provincial welfare systems. Benefits for injured workers and disabled people must be greatly increased, rendered secure and free of bureaucratic intrusion. However, at such a crucial time, the focus on extending the cash benefit system is a serious mistake that increases the power of the capitalist marketplace, rather than limiting it.

Why should we make our peace with the neoliberal reordering of the workforce in the form of an employers’ subsidy? Let’s demand minimum wages that workers and their families can live on. Let’s take up the struggle for workers’ rights and reduced hours of work. A rejuvenated trade union movement that went on the offensive could win these things.

Instead of reinforcing the commodification of social provision, let’s put our efforts into making real gains across a wide range of vital public services. A huge expansion of social housing would ensure that wages and income presently being handed to corporate landlords are put to much better use. There are so many gains we can make that would serve us much better than a basic income. Far from suggesting any piecemeal approach, its time to hammer out a wide ranging set of basic demands and a plan of action to fight for them.

I don’t expect the debate on the left around basic income to be resolved any time soon, but in the meantime let’s not assume that participants on one or the other side of the issue have a monopoly on sincerity, good intentions or deeply held conviction. It’s a substantive disagreement, with positions on both sides being taken by people who share many of the same values and objectives. I don’t think my enemies are those who honestly feel that basic income is the best approach. Rather, they are those who maintain the system of colonialism, racism and poverty that Leah Gazan condemns so powerfully. The stakes are too high to set the debate aside, but I hope we can pursue it in ways that are useful and constructive. In that spirit, I offer this response to what is, in my view, the mistaken notion that basic income offers us a way forward.

John Clarke is a writer and retired organizer for the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP). Follow his tweets at @JohnOCAP and blog at johnclarkeblog.com.

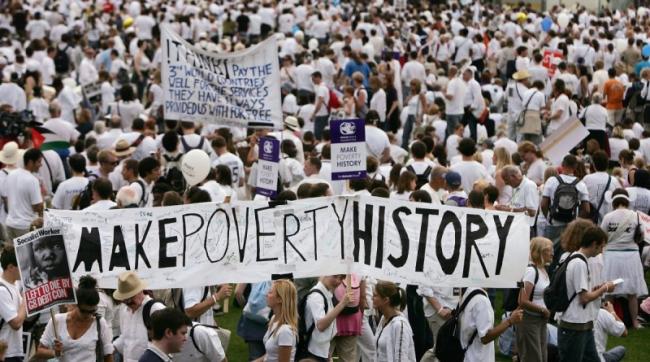

[Top photo: A MakePovertyHistory march attended by an estimated 200,000 people before a G8 Summit in Edinburgh, Scotland, July 2, 2005. Photo by Bruno Vincent.]