Articles Menu

Jan. 21, 2025

In his new book Power Metal: The Race for the Resources That Will Shape the Future, Vancouver journalist and author Vince Beiser takes a critical, sobering look at the metals required to power the digital devices and systems we’re relying on to save the planet.

Huge amounts of copper, nickel, cobalt, boron and lithium are necessary to power the batteries and chips that support technologies like smartphones, electric vehicles and the internet and green energy sources like wind turbines and solar panels. The cost of mining and refining these materials, Beiser argues, is far greater than we realize.

On Thursday, Beiser will be at the Vancouver bookstore Upstart & Crow on Granville Island for a conversation with Christopher Pollon, author of Pitfall: The Race to Mine the World’s Most Vulnerable Places.

And last week, at Main Street’s Liberty Bakery + Cafe, Beiser was in conversation with The Tyee about the critical message of Power Metal, the environmental and humanitarian problems created and exacerbated by our collective pivot to these new products and technologies, and whether or not it’s truly possible to implement the sweeping changes necessary to offset or limit the damage inherent in the pursuit of our sustainable future.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The Tyee: First of all, congratulations. But also, thanks for nothing, because I rode my e-bike here thinking I was saving the planet, and then I read your book. I’m not really saving the planet at all, am I?

Vince Beiser: You’re doing less damage to the planet. Which is good! Which is not nothing.

It feels like every time we find a new Earth-saving approach to commuting or what have you, it turns out that, actually, it’s still doing quite a lot of damage to the planet. The electro-digital age has been sold to us as a solution to climate change. But in Power Metal, you lay out the incredible cost of extracting the rare metals and minerals that go into our phones — and my sweet, sweet bike — and the damage they’re doing.

One of the themes of the book is that everything has a cost. We want to believe that we’re saving the planet. But basically nothing that we do as human beings is helping. We’re just doing harm to it. If you look around us, there’s nothing natural about where we’re sitting.

I do see one tree over there.

Now, there are things we can do. There are much better approaches. That being said, everything is going to also entail some cost of its own. And that’s sort of what the book’s about.

In order to build all these things, all the solar panels and wind turbines and electric vehicles and even e-bikes, not to mention our cellphones and all of our digital gadgets, we need metals: raw materials from Europe and billions of tonnes of copper, cobalt, nickel, lithium — a whole list of metals in order to build those things.

Once we get them up and running, it’ll be better than, you know, fossil fuel power. But the extraction of all those things and the scramble to get all those billions of tonnes of metal... We’re cutting rainforests to the ground in Indonesia, putting children to work in mines in the Congo, rivers are being poisoned all over the world.

But we need these things, right? We need to switch from fossil fuels over to renewable energy. We need to switch from gas cars to electric vehicles.

So how can we do it better?

How can we do it in ways that are cleaner, more humane, more sustainable?

Can we? I mean, obviously, kids working in mines is an objective bad. But a lot of these new approaches have been sold to us as objective good, and that sure doesn’t seem to be the case.

Yeah, it’s not. I mean, electric cars are better than fossil fuel cars, because the biggest threat of all is climate change, right? So next to that, all the harms that I’m talking about are lesser. But they’re a long way from zero. That’s part of the story that I wanted to tell. Nothing comes without a cost.

You return to that phrase several times in Power Metal, and each time it’s really quite jarring, because the cost is so significant. And each solution seems worse. You talk about the people pushing to mine the ocean floor, instead of brutalizing the above-ground part of the Earth, and then we learn there’s no way to do that without “utterly annihilating the bottom of the sea floor.”

Even beyond the environmental cost, there’s the social cost: the way that people are being treated, the kids, Indigenous communities being threatened and displaced, wars, geopolitical problems... all because of this race to extract the minerals that will supposedly make this a better world. It just seems like whatever we do, it’s just continuing to cause harm.

Wow, that’s a bleak takeaway.

I’m sorry, but I read the book.

There’s always downsides. That’s a given. But I don’t want anybody to walk away like, “Oh, my God, it’s hopeless.” Because, again, there are a lot of things that we can do to bring the damage down.

And ultimately, the goal is not utopia, right? That’s not realistic. That’s just a fantasy. But I do believe that we can get to a place that’s sustainable, where the damage is not continuing to increase, where we’ve sort of got it contained.

Because right now, we’re on a trajectory where the harm — mainly in the form of climate change, but also in all these other ways — is getting worse and worse. And eventually, maybe pretty soon, they’re gonna reach a point where it becomes catastrophic.

We can change that trajectory. I do believe we can.

But then you get into the business of recycling. Turns out it’s a dirty business, it’s a dangerous business, and we are terrible at it. You said that we recycle less than one per cent of the lithium we mine. And only 17 per cent of all e-waste is collected and recycled. I wonder sometimes when people talk about recycling: are we even really doing it? Because it seems like we don’t do much of it at all.

I felt the same way, right? When I started on this, I thought: Recycling, that’s the answer. We’ll just recycle more, and everything will be fine. And I want to be clear: recycling is better, just like your e-bike. It’s much less harmful. But it also has a lot of its own costs. There are two big problems: we don’t do nearly enough of it and, often, the ways we do it are very energy-intensive, very polluting and done on the backs of the poorest people in the world.

It can seem very counterintuitive. And at the same time, we offset a lot of our effort by continuing to make more and more stuff.

There’s a fundamental contradiction between sustainability and capitalism. Sustainability basically says: Stop growing. Reach a level where, kind of, everybody has enough, and then just maintain. Go into cruise control from there.

Capitalism says: No, you gotta grow, you gotta always be making more and more. So that is a fundamental contradiction that is somehow or another going to come to a head right in the coming decades.

It’s either going to be, the world is simply incapable of continuing to support endless growth and systems just start collapsing, which is already starting to happen, or somehow or another, we rein in, mutate, evolve capitalism — our economic system. Direct it. Harness it somehow, so that it’s doing more to serve human needs, rather than just continuing to grow. And that’s not impossible.

Tell me how that’s not impossible.

OK.

Please tell me.

One hundred years ago in this country, in Canada, the U.S., the mining that used to happen here was just nightmarish, right? They would just go in and strip-mine the hell out of wherever it was. Dig these enormous pits in the ground. Dump their toxic waste in the rivers, or wherever they felt like it. Set up their smelters, belch out smoke that was filled with enough toxins to kill cows for miles around, and then when the copper or silver or whatever was gone, we’d literally walk away.

That’s how it was done here. And you can still see the scars all over B.C. Go to a place like Greenwood, a few hours from here. Outside of Greenwood, there’s a gigantic copper slag pit. It’s just basically a dead zone. That’s where they used to dump all the copper junk, all the molten slag from the furnace.

You can’t do that anymore because, basically, the government stepped in and created a whole system of rules and regulations. You cannot do that. You can keep making money. You can continue to operate a mine, but if you’re gonna operate a mine, you have to abide by these rules.

You have to pay your workers. You have to make sure they have safety equipment. You can’t dump your crap in the rivers, and if you are gonna dump your crap, you’ve gotta make sure you filter out these chemicals and those chemicals. And as a result, mining still causes a lot of damage, but it’s way less. The amount of harm that mining does here is much lower than it used to be.

So now they just mine overseas, where there’s less regulation and oversight.

But one can imagine a world where, you know, all governments did that, where there was some kind of international standard, which is something that a lot of folks are working towards. Set a base level, right? You’ve got to minimize the environmental damage. You’ve got to follow regulations. You’ve got to follow labour standards. You can keep making money. You can keep mining and making stuff and selling stuff. You’re probably not going to make as much money as you were before, but too bad. Because otherwise you can’t make any money at all. And I do think that’s doable.

Speaking a little more locally, you talk in Power Metal about the need to improve sustainability by redesigning our cities and suburbs, especially for walkability, cycling and improved transit. But how do you persuade these cities, these governments, to remake these places? So long as we’re fixing the whole planet, what can we do as a collective to urge some of these changes?

Well, I’ll tell you, I don’t know what happened in Vancouver, but whatever it was that happened here, people should study it. Because I was a bike messenger here back in the ’90s, riding my bike around downtown Vancouver all day, every day. There were no bike lanes. The concept didn’t even exist. You ride your bike in the middle of traffic with all the other cars. And nobody thought twice about it. The notion of a separate lane for bicycles just did not even exist.

It still makes some people mad.

But I just moved back here about five years ago, and I’m continually amazed. I just ran errands on my bicycle. The whole way I was on bike-protected streets and bike lanes, and I felt 100 per cent safe and unworried, because we’ve got a really good bicycle infrastructure that’s been built up over the last 20 years or so.

I’m not really sure when it started. But it’s really good, and that did not exist before. It’s not like Vancouver was purpose-built with that. We retrofitted that onto a city that had been built for cars.

And now it all comes full circle for me and my e-bike.

And walkability, right? Like, I mean, here we are on Main Street. You know, half the streets between here and Broadway are blocked off to cars. They’ve got the cute little roundabouts with flowers in them so that you can’t drive through, so that it’s quieter and it’s safer, and it makes it way more pleasant for people to walk around.

That’s probably why they call it Mount Pleasant.

All of this is to say it can be done. It takes people in power. It takes government officials prodded by activists, environmentalists, urban planners. It’s not easy. But it’s definitely doable.

Join Vince Beiser in conversation with journalist Christopher Pollon at Upstart & Crow, a bookstore on Vancouver’s Granville Island, on Thursday from 7 to 9 p.m. The event is free to attend; register here.

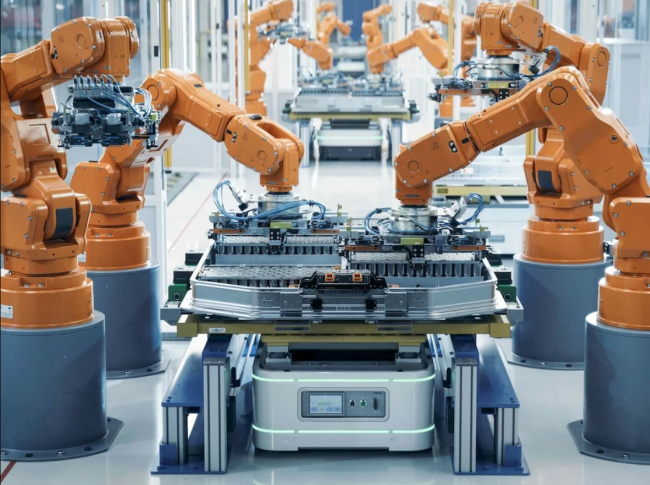

[Top photo: An automated production line uses robots to manufacture electric vehicle parts. EVs were built in response to climate change, but these and other technologies carry hidden costs, writes Vancouver journalist Vince Beiser. Photo via Shutterstock.]