Articles Menu

Oct. 13, 2021

[Tyee Editor’s note: Tyee contributor Arno Kopecky’s new book, The Environmentalist’s Dilemma, does not offer panaceas or easy answers. Instead, it engages head on with paradoxes, dilemmas and nuance — not to mention issues environmentalists often avoid, like “overpopulation.”

In this excerpt, Kopecky explores the white supremacist roots of some of the West’s foundational environmentalists, and how these roots make collaborations between mainstream environmental groups and Indigenous peoples complex to this day.

We have also published an interview with Kopecky today. Read it here. You can also catch him in conversation with J.B. MacKinnon at the Vancouver Writers Festival on Oct. 22 at 2:30 p.m. PDT, at Performance Works.]

In his 2017 essay “Canada’s National Parks Are Colonial Crime Scenes,” the Kwantlen journalist and author Robert Jago laid bare the terrible social cost of Canada’s earliest environmental impulse.

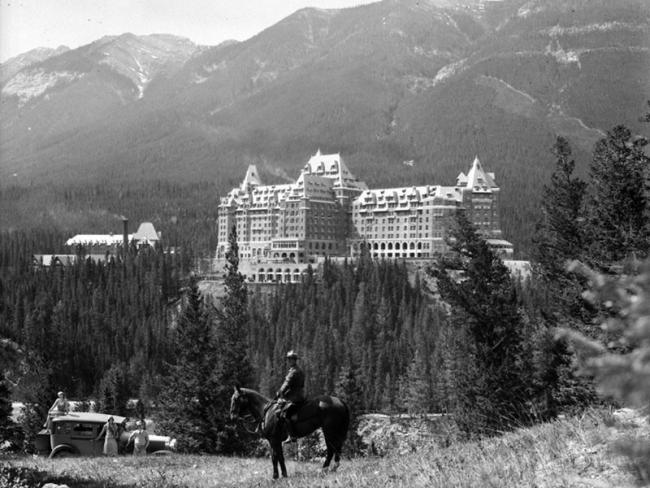

“Canada’s parks departments have treated Indigenous peoples like an infestation ever since the founding, in 1885, of Banff National Park,” Jago writes. Not only were Indigenous peoples forcibly evicted, they were also barred from returning for any reason. Jago quotes George Stewart, the park’s superintendent at the time, who complained of the Indigenous presence in Banff that “their destruction of the game and depredations among the ornamental trees make their too frequent visits a matter of great concern.”

And so the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Tsuut’ina Nations and the Stoney Nakoda Nations were banished from their territories, as were the Indigenous occupants of the land transformed into every national and provincial park that sprouted across the country in subsequent years. Not content to stop there, Canada’s legislators decided the land’s original inhabitants should be confined to isolated patches of unproductive earth, the more remote the better, which they could only leave with special permission from the local Indian Affairs officer. This reserve system became a political tourist attraction, drawing legislators from South Africa who studied and then used it as a model in creating the infrastructure of Apartheid.

You won’t see any of that context in a Group of Seven painting. Nor will you see the rich Indigenous history that preceded the colonial crimes Jago describes so painfully in his essay. “The places Canada has made into parks are filled with our stories,” Jago writes. “Every mountain, every valley has a name and a history for Indigenous peoples. It is in these places that our history is alive: our Mecca is here, our Magna Carta, our Thermopylae.”

In the 1930s, while Afrikaners were touring Canada, a newly minted Nazi party began studying the 19th-century U.S. legislation that created the legal architecture for America’s pursuit of genocide. In the U.S., the project was described as “pushing the western frontier.” The Germans boiled it down to “Lebensraum,” and their substitution of Jews and Poles and Czechs for Sioux and Shasta and Mojave made the horror of its execution abundantly clear to most Americans. What it didn’t do was cause many of those same Americans to reflect on their own historical embrace of the very same policy.

. . . . . . . [Read more of this excerpt here.]

Arno Kopecky is an environmental journalist and author. His two previous books are The Devil’s Curve and The Oil Man and the Sea, a finalist for the 2014 Governor General’s Literary Award. He lives in Vancouver.

[Top photo: Banff was Canada’s first national park. The federal government departments responsible for parks have treated Indigenous peoples ‘like an infestation’ ever since Banff’s founding, Robert Jago wrote in a 2017 essay for the Walrus. Photo by William John Oliver, courtesy of National Parks Branch / Library and Archives Canada.]