Articles Menu

Nov. 21, 2024

So, the election of Donald Trump and likely coronation of Pierre Poilievre have you thinking there’s no point in pushing back so you might as well can your political activities and spend all your time hunkered down in a defensive crouch? Think again. If we take the long view, we see that the common people have a long history of overthrowing their oppressors, even when objectively the possibilities for change look hopeless.

Humans lived in equal, peaceful societies for the 97 per cent of our existence as a species when we were exclusively foragers. Some would have you believe that we’ve been descending to barbarism ever since. Beware of what they leave out — the persistent spark of resistance throughout recorded history, in service of visions of more humane, egalitarian societies.

Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari helped reverse the argument that humans have progressed from savagery to civilization in his book Sapiens. But he did largely leave out some key actors, by focusing on the technologies and ideologies of the ruling classes rather than on the activities of the masses.

Harari doesn’t mince words. He proclaims that “the Agricultural Revolution was history’s biggest fraud,” the destroyer of equality. He regards the Industrial Revolution as a close second. Still, while Harari denounces inequalities, he virtually ignores the revolt of slaves, serfs, working people, women and colonized Indigenous Peoples throughout the post-foraging period.

Anthropologist David Graeber and archeologist David Wengrow, both committed anarchists, offer a more complex account in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Early farmers, being former foragers, did preserve collectivist values. But the authors’ antipathy to state-organized societies causes them to join Harari in ignoring efforts the masses made in the last 5,000 years to restore the equality of earlier times.

I provide many examples of such moments in my new book Humans: The 300,000-Year Struggle for Equality. Here are some:

In Sparta, during the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, 80 per cent of the population consisted of enslaved captives. They did all the non-military work, and they rebelled constantly. The Spartan vaunted militarism was dictated by the need to simultaneously defeat rivals and suppress the slaves. Sometimes slave revolts forced Sparta to grant islands to the rebels where they ruled themselves in an egalitarian fashion.

Sparta’s rival Athens was a three-class society characterized by endless slave revolts and revolts of free commoners against the ruling aristocracy. The aristocratic experiment in democracy from 508 BCE to 322 BCE resulted from fears of the small, land-rich ruling group that simultaneous slave and commoners’ revolts would overwhelm them. They had two options. They could free captive slaves and make them a bulwark against the free Athenian-born. But then who would work in their palaces and on their land? The other possibility was to grant free commoner males an assembly with restricted powers and opportunity to serve temporarily on the paid executive group by winning a lottery.

The three-year “Spartacus revolt” from 73 to 71 BCE was brutally suppressed with over 100,000 slaves killed. While the regime declared the continued right of slave owners to own slaves, slave-owner fears of being killed in their beds by their chattel led to manumission of most slaves, though the newly freed slaves were subjected to extortionate “tributes” to their former masters.

The so-called Dark Ages that followed the fall of tribute-demanding Rome were, from a certain perspective, a brighter time than the name implies. During the stretch of centuries from the late 400s to the early 1000s, peasants established democratic community governments that distributed land equally and guaranteed reciprocal protections, including local militaries. Feudalism, which the ruling class claimed exchanged protection by armed lords for peasants working half the week on the lord’s land, was viewed as a mafia extortion scheme by peasants. They fought its establishment, and in much of Belgium and the Netherlands, the would-be feudal lords proved unable to conquer the people. Where feudal lords prevailed, they faced constant revolts. In parts of Spain, even as that nation plundered the Americas, feudalism was defeated.

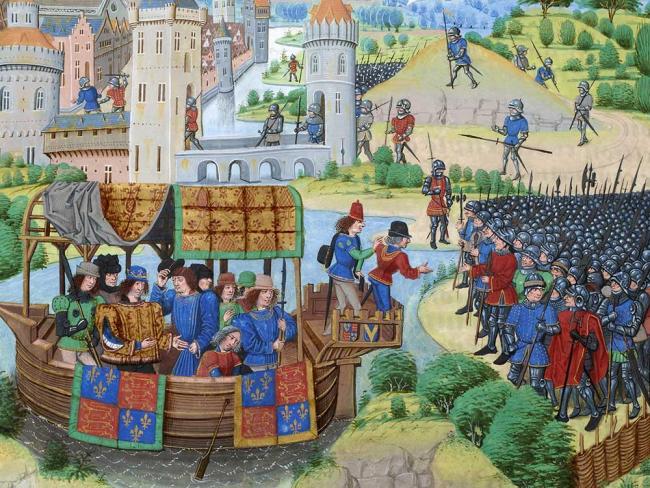

The 1381 English peasant rebellion was led by women. Initiated by Johanna Ferrour in the county of Kent against imposition of a crushing poll tax, it transformed into a revolt against feudalism as the Kent rebels were joined on a march to London by over 100,000 people. Rebel women murdered the Archbishop of Canterbury and burned castles of aristocrats. Women’s leadership in peasant revolts and liberation struggles are understated by historians when they mention such revolts at all.

Peasant revolts in China produced the fall of several dynasties. The Ming Dynasty that smashed the Mongol Empire in the 1350s put a poor peasant in power in China.

Rebellions of conquered Indigenous Peoples in the Americas sometimes forced European conquerors to allow re-establishment of Indigenous sovereign states. That included areas of the British North American colonies, plus Spanish-controlled Mexico, Chile and Argentina. When colonizers won independence, one of their key goals was to seize lands the imperial power had ceded to Indigenous people.

Slaves in the United States overthrew the system that oppressed them. Their constant uprisings and escapes horrified their masters and put them in no mood to accept Abraham Lincoln’s plan to end expansion of slavery. That led to the fight that ended slavery altogether.

Working-class threats of revolt after the Second World War, not ruling-class compassion, created the welfare state. That in turn reduced unemployment and made it possible for unions to organize more workers and win improvements in their lives. Workers have fought the neoliberal attempt since the late 1970s to deregulate capitalism and privatize the public sector, resisting attempts to upend the “historical compromise” between capital and labour. Capital has fought back with efforts to divide working people on the basis of race, gender and gender orientation.

Ruling classes always practise divide and conquer. But the message from the past is that unity against oppressors can occur and no economic system, including capitalism, can be viewed as permanent.

Athabasca University emeritus professor Alvin Finkel’s latest book, Humans, is one of Chapters’ top 100 new books of 2024.

[Top: A detail from a painting by Jean Froissart of Richard II meeting with the rebels of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Image via Wikimedia.]