Articles Menu

May 17, 2022

In their electoral platform for the fall election, Québec solidaire, which has 10 MPs out of 125 in Quebec’s parliament, is proposing to achieve a reduction of greenhouse gases (GHGs) of 55 to 65% by 2030. But as the awareness of the climate catastrophe is becoming widespread, so is the pessimism that it cannot be countered… for the greater benefit of firemen-arsonists. Taking advantage of the eco-anxiety that boosts the reflex of a return to post-pandemic normal, as well as the energy insecurity resulting from the war against Ukraine, the lead capitalists propose an immediate reinvestment in hydrocarbons, which GHGs will be absorbed by negative emission technologies (capture and sequestration of GHGs during their emission or directly from ambient air).

Since, on the one hand, these new production infrastructures could not theoretically be amortized over the long term and, on the other hand, these capture-sequestration technologies are not mature, are risky, and very expensive, such investments would open a new and gargantuan investment field for capital… if it is fully subsidized by the State. One can guess at the counterpart of austerity and repression that would result.

Renewable Energy as a Pivot is a Dog Chasing its Tail

The COVID pandemic and the Ukrainian war are catalysts and justifications of this capitalist strategy by sharpening the contradiction between, on the one hand, the yo-yoing demand in fossil energy, initially slowed down by the pandemic and then accelerated by the will to boycott Russian hydrocarbons immediately considered by speculation, and on the other hand, by the rate of construction of renewable energy equipment. As the supply of energy, whether in hydrocarbons or renewable energy, is under the control of a handful of transnational corporations supervised by a few large states, these latter, according to current events, in the last analysis, to the capitalist dynamics generating pandemics and wars, have a nice game of creating an acute scarcity of energy sources in order to arouse panic. This scarcity increases prices in the short-term for their biggest profits (and military spending of oil states). In the long-term, it legitimizes the extension of the energy transition well beyond the limits set by the UN-IPCC to take the time needed to amortize their hydrocarbon production infrastructure… unless there is state compensation.

At first sight, the solution to this contradiction would be to weigh on the accelerator of renewable energies even if it means either making the necessary nationalizations or ensuring sufficient state control. This is the solution of social-liberal green capitalism, with its carbon tax or market, or reformist with its weak or pronounced state interventionism. However, as renewable energies are diffuse and unstable compared to fossil fuels, they require a much higher equipment-to-energy ratio (and considerable installation space), not to mention that the production of this equipment (cement, steel, silicon panels) is energy intensive and the energy needed to do so will initially be fossil-based at 80% on average, given the current global fossil-renewable ratio. This apparent solution is finally proving to be a dead end given the climate emergency: “the IPCC says that for a 50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C by 2100, no more than 500bn tonnes of CO2 can be emitted beyond 2020, equivalent to little more than a decade of emissions at current rates.”

To achieve this through the substitution of hydrocarbons by renewables, including hydroelectricity, in the context of the inevitable capitalist growth, “[g]lobally, emissions from the energy sector must decrease by 2.2 to 3.3% per year until 2050 to stay below 1.5°C” (Daniel Tanuro, IPCC Report: from scientific rigour to social fable, ESSF, 4/04/22). To achieve such a feat, the energy-to-production ratio and the GHG-to-energy ratio would have to fall rapidly. However, by combining these two ratios, “[b]etween 2010 and 2018, the increase in average GDP per person increased fossil CO2 emissions by 2.3%/year, while population growth increased them by 1%/year.” More precisely, “[t]he most intensive activities in terms of greenhouse gas emissions [have] increased strongly during the decade 2010-2020: +28.5% for aviation, +17% for the purchase of SUVs, +12% for meat consumption” (Daniel Tanuro). All in all, not only is the solution of renewable energies, other than as a complement, a dead-end but the mode of production and consumption associated with it aggravates the contradiction. This mode, it should be emphasized, is based on exponential material production and mass consumption, of which the solo car and the solo house are the pillars, urban sprawl the mode of land use planning, and deforestation the inevitable consequence of the meat diet.

The green capitalist strategy of substituting so-called renewable energies for fossil fuels is therefore unrealistic. To make it realistic, green capitalism proposes to attach negative emission technologies to it, with disastrous socio-economic consequences as we have seen. But this addition would not help because we would have to build the necessary infrastructure on a gigantic scale to make a difference, not to mention the uncertainty of the results. However, regarding infrastructures producing renewable energies, these infrastructures require an energy-intensive Everest of materials demanding 80% of fossil fuels globally to produce them as well as to operate them. Capitalist growth encloses the world in a vicious circle that leads it to existential catastrophe. Working Group III of the recently published IPCC Sixth Assessment Report came for the first time to consider that “[c]limate stabilization cannot be achieved without a very substantial reduction in final energy consumption – a reduction so significant that it necessarily implies a reduction in material production and transport” (Daniel Tanuro). To this must be added an agrobiological revolution with meat reduction.

The primary goal of any action plan to achieve the IPCC objectives will be to substantially reduce global energy consumption based on the precautionary principles of historical responsibility and the ability to pay being accepted by all countries party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Rio in 1992. For Quebec, on the eve of the COP-26 in Glasgow, a range of key organizations (the Climate Action Network Canada, the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec, Équiterre, Greenpeace, Nature-Québec, the David Suzuki Foundation, and Oxfam-Québec) called for an internal target of 65% as the medium term of an overall target of 178%. These targets are justified by the fact that “internationally, Quebec’s fair share also requires international cooperation, especially with the countries of the South to support their GHG emission reductions” (Climate Action Network, La juste part du Québec dans la lutte pour les changements climatiques).

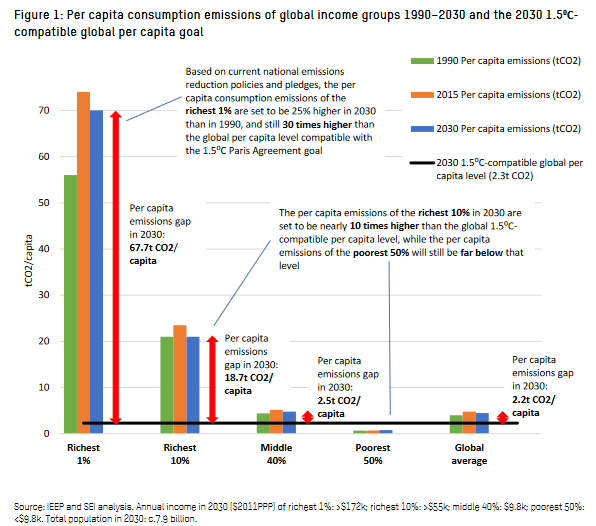

The forgotten aspect, until recently, of the study of the causes of the climate crisis (and of the concomitant one of biodiversity) in the light of the Rio principles had been inequalities not between countries but between individuals according to income brackets within national borders as well as globally. As NGOs EcoEquity and the Stockholm Environment Institute have developed a country calculator based on the Rio Climate Equity Reference Calculator, which allows for a range of combinations, and which was used to calculate the Quebec targets mentioned above, NGOs Oxfam and Institute for European Environmental Policy have calculated carbon inequality by income bracket (Carbon Inequality in 2030), from which the following graphic is drawn and which speaks for itself:

We see that it is the GHG emissions of the richest 10% of humanity that are the problem, especially those of the 1% denounced by the Occupy movement. The key to achieving the IPCC targets lies in drastically reducing their consumption patterns in favour of a substantial increase, in relative terms, of the poorest 50%. The strategic trap in which we could fall here would be to make a moral appeal to individuals to reduce and modify their consumption the lead line of the transition action plan even if it also means policies that strongly encourage and penalize them.

It would be to stick to carbon taxes or market and bonus-malus programs to choose the right products or services while the structure of the consumption mode is biased pro-carbon (for example, the lack of public transit in the suburbs and regions and the paralysis by car traffic in the city centre). The fatal error of this strategy is the hypothesis that we can revolutionize the mode of consumption, which we must indeed do, without revolutionizing the mode of production on which it is based. It is a question of targeting the 10%, and mostly the 1%, not so much as boors of consumption, but rather as owners and controllers of the means of production, the masters of the universe and its laws, which is the source of their income for their luxury and ostentatious consumption. It is this source that must be dried up by cutting short the private ownership of the means of production.

Appealing to individuals to spend their fortunes ecologically will give some pseudo paths of Damascus style tax-subsidized charitable foundations that will in no way change the capitalist foundation of the mode of production. It is its law of competitiveness between private capitals, the corollary of which is that between the States leading up to wars, which obliges capitalists to grow or perish. The forced growth of one, the production, leads to the forced growth of the other, the consumption, including the military and security apparatuses of the State. The result is the mass consumption by the so-called middle classes – roughly 40% of the figure above – based on the individual ownership of the lodging (the solo house) and the means of transport (the solo car). This consumer accumulation mimics capitalist accumulation while chaining the so-called middle classes by their indebtedness (mortgage credit, etc.), to the financial capital which, in addition, rolls out the red carpet of investments for retirement, making them slaves of capitalist profits.

The distribution of the responsibility for GHG emissions by income brackets against the background of the economic and political power of the 1% supported by the 10% and the ambivalence of the next 40% sets the table for the determination of each other’s strategy. The radical right, which refuses the climate struggle, seeks to unite by populism the middle classes of the 40% against not the 1%, except rhetorically, but against the racialized part of the 50%. This tends to rally to them the desperate part of the ‘native’ of the same category. The traditional centrism of the top 10% proposes a climate struggle within the framework of the market economy which weighs more or less fiscally on the wealthiest 50% to support the poorest 50% depending on whether this centrism is right or left. The climate struggle of the left, whose base of support is the bottom 50% to lead the higher 40%, wants to put an end to the domination of the market to revolutionize the modes of production and consumption so as to drastically reduce material production through profound reforms of land use planning, urban planning, housing, transport, energy, and agriculture.

The bracketing of the market is not foreign to capitalism when its vital interests are in question. The typical example is the production for war purposes when the big tenors of the major corporations fit into the state apparatus to transform tail over head, and in less than two, the economic structure into a war economy. We note that less drastic but deemed politically indispensable transformations such as the American program for the first moon landing, the modernization of the socio-economic structure of Quebec known as the Quiet Revolution, the reconstruction of Europe ravaged by war was accomplished by a strong state intervention spread over 10-20 years such as the French plans. If we see no similar mobilization for the climate fight despite its urgency and if its survival stake is that the required transformation is antithetical to capital in the sense that it requires a monumental decrease in material production which kills the accumulation of capital, we are doomed. Capital is only ready to take the dead-end path of negative emissions under the protection of an extreme-centrist dictatorship inevitably leaning toward fascism with the disasters that will pile up.

The so-called realists of this world will plead the utopianism of the left way because the 50% richest and more would reject out of hand such a fall in their standard of living. This is the deceptive paradox of the market economy: GDP per capita, in addition without considering its distribution, has nothing to do with the standard of living, better called standard of well-being. The human being, beyond modest physiological needs, because of its evolution since the dawn of time, requires solidarity and more solidarity for its free development, which will enrich this solidarity both toward its species and toward the whole of nature of which (s)he is a stakeholder. Not only does capitalism not meet the basic needs of all, not even so much in the so-called rich countries, but instead of creating social solidarity, it destroys it to make the atomized individual an accumulator of tangible products and fictitious capital as a safety stopgap and a mean of social recognition. Capitalism fills even basic needs at the expense of nature by means isolating individuals from each other (solo housing and car), harming their health (meat diet, processed food), and giving them empty and debilitating pleasures (entertainment, alcohol, drugs).

The problem is to go from A to B, what is known tautologically as transition. But politically, it is rather a question of rupture, first and fundamentally against the 1% from whom, by a revolutionary mobilization made of strikes and blockades, it is necessary to wrest power in order to socialize, in one way or another, the strategic sectors of the economy, which are finance, in order to control national savings and international monetary flows, the communication and transport networks that structure social relationships, the energy system that moves and cools society, the agriculture that sustains it, the habitat that shelters it, and the health and education that nurtures and educates it. The conditions will then be met to bring down material production by giving all the space to land-use planning made of collective transport and energy-efficient habitat, urban agrobiology and short journeys, green landscapes without advertising; sustainable, repairable, reusable, and recyclable products; an ecofeminist society caring for people and for Mother earth based on drastically enhanced public services and on the safeguarding of ecosystems.

This climate justice – social justice perspective is reflected in the 2022 Québec solidaire electoral platform. The party commits to stop all exploitation and transportation of hydrocarbons, to “reduce Quebec’s emissions by at least 55% compared to 1990 levels by 2030,” and “to question international economic and military agreements and conventions signed by Canada.” From the first term of office, it commits itself to propose a referendum for independence following a Constituent assembly while promoting French as an official and common language. These are firm and strong commitments to break with the finance-oil Toronto-Calgary axis which defines the Canadian economy as well as with Ottawa’s federalism, which submits to American imperialism and flouts the pre-eminence of French in Quebec. It is this ecological and full left independence that is the guarantor of this rupture for the socialization of vital sectors of Quebec society, whatever the party’s parliamentary wing says or does. It is up to the party’s militancy and the people of Quebec to ensure that their party does not get bogged down in parliamentary cretinism, as has been unfortunately demonstrated by an electoral centrism of the parliamentary wing that seems to want to consolidate itself.

This radical and necessary perspective could all the more be advanced by Québec solidaire during the elections this fall as the social struggle situation begins to send signals of rebound. We note recently both in the US and in Quebec and probably elsewhere, spurred by inflation, a modest rise in strikes. Similarly, the recent failure of the Common Front, the usual big union meeting in Quebec for more than half a century, has prompted some of the most important central trade unions to rebuild it, at least from the top, in view of the next public-sector confrontation after the fall election. If the visible resumption of the debates within the inter-union militancy could go beyond the usual blah-blah, this announced renewal of the Common Front could be consolidated from the bottom and eventually take the initiative at the expense of the trade union bureaucracy, which left to itself indulges in the usual compromises.

A Common Front under rank-and-file control has the ability to take the first steps on the bridge from point A to point B, for example, by fighting not only for a catch-up and an indexation of wages but also for the hiring of at least 100,000 people in the public and community sectors, to start a major construction project of at least 10,000 energy-efficient social housing units per year and for free public transit, including the investments needed to meet demand. Such demands, combined with a Solidaire platform, which already contains them, put forward and not put under the carpet as in the 2018 election, are able to awaken the spirit of the quasi-insurrectionary uprising of the 1972 general strike, with its beginning of pre-revolutionary situations, whose fiftieth anniversary is too little celebrated. •

This article was published in French and translation by author, on the Presse-toi-à-gauche.

Marc Bonhomme is a long-time socialist activist, economist and writer on the Quebec left. His writings can be found at marcbonhomme.com.