Articles Menu

Jul. 31, 2023

[Tyee Editor’s note: This piece is drawn from a recently published version on Markham Hislop’s site Energi Media.]

Can you imagine a world in which Alberta’s bountiful oil reserves are used for manufacturing space-age materials instead of refined to become climate-destroying fuels? If you can’t, you’re not alone. Neither can Alberta’s leadership. Nor oil company CEOs or politicians or the business community.

That needs to change. And Canada, the rest of Canada, needs to help Alberta with that change.

That means helping to imagine, then build, a post-combustion economy before the global energy transition guts the province’s century-old oil and gas business model. Fail, and the consequences are likely to be profound for the country’s economy and climate targets. Succeed, though, and entirely new industries could be created whose benefits would be felt across Canada.

What could Alberta’s new post-combustion economy look like? Many of the building blocks already exist, but they’re at an early stage — sometimes a few startups, but often still in the lab. The opportunities, though, are nothing short of amazing.

Done right, post-combustion Alberta could be more prosperous than ever, as I discussed in a video interview with economist Chris Bataille, “How Alberta oil/gas can decarbonize AND transition to new net-zero products.”

Full disclosure: the Alberta Federation of Labour hired me as a freelance writer last year to help draft the “Skate to Where the Puck is Going” report. That report, as an AFL announcement summarized it at the time, “describes seven ‘missions’ that will transform the Alberta economy.

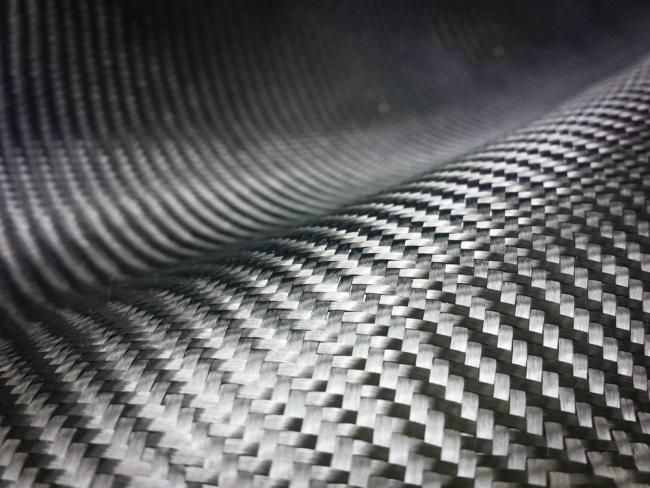

“The most significant is transitioning the oil and gas sector from producing feedstock for refining fuels like gasoline to producing feedstock for materials manufacturing like carbon fibre. This includes manufacturing products from captured carbon dioxide.”

Why should Canadians care?

The tiresome chest-thumping from Alberta’s conservative politicians about being Canada’s economic engine elicits eye rolls in other provinces, but there’s some truth in the claim.

Oil and gas is the biggest export sector by far, over $100 billion per year, twice that of automobiles, and Alberta produces 80 per cent of that oil, and two-thirds of the gas. The province’s capital-hungry industry gobbles up over $30 billion per year, one-tenth of the national expenditure. The economic impact of that capital is felt in other provinces, but particularly in the most populous: B.C., Ontario and Quebec. Alberta punches above its weight in GDP.

And over 122,000 workers — er, voters — are directly employed by the industry. Ok, you get the point: Alberta is important to Canada’s economic prosperity. Canada needs Alberta.

But Alberta also needs Canada.

Alberta plans for the best, ignores the worst

Remember our mother’s wise advice to hope for the best but plan for the worst? Alberta missed that lesson.

Its political and business elite is heavily invested in the Vaclav Smil view of energy. The dean of energy transition scholarship, professor Smil insists that global energy systems change very slowly over many decades. Rising demand in developing economies will more than offset decline in advanced countries, the argument goes, with more than enough demand to support the increasingly competitive Alberta industry well past 2050.

Don’t worry, be happy, Alberta oil companies, your best-case scenario is all but assured.

No surprise, Smil is a god in the Calgary Petroleum Club.

But Smil isn’t the only smartypants thinking about the energy transition. There are plenty of analysts who think the energy transition is coming for fossil fuels sooner — for some, much sooner — rather than later.

I have recorded interviews with a few of them. Long-time clean energy executive Mike Andrade explains the difference between energy as a commodity (coal, oil, gas) and energy as a technology (wind, solar, batteries). The peak demand-bumpy plateau-rapid decline transition model is explored in-depth by Kingsmill Bond of the Rocky Mountain Institute. In another video conversation he said, “From deep energy crisis comes profound energy transition change.” And noted American economist Phil Verleger, who advised presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, argues that oil is already a sunset industry.

According to these thinkers, in the not-too-distant future Alberta’s mighty oil and gas industry could be staring down the barrel of intense disruption, low and increasingly volatile prices, and acceleration of the corporate failures that started in 2015 with the last great oil and gas bust.

But this will be a bust unlike any other. After a 125-year run, instead of cyclical, decline will be structural and permanent.

Once Alberta is on that slippery slope, there is no coming back.

How should Alberta think about the energy transition?

The slow and fast schools of transition actually agree that fossil fuels will be eclipsed by clean energy. They just disagree on the timing.

But timing in this case is everything, so what are Alberta’s options? There are three.

Listen to the rapid transition thinkers and plan for the worst by immediately creating an energy transition strategy.

Heed professor Smil and stick with the status quo, which has already made Canada the fourth largest oil and gas producer in the world.

Or, double down on the status quo and argue for a massive expansion of hydrocarbon production and construction of more pipelines, essentially ignoring national climate targets and the existential threat posed by the rapidly accelerating switch from fossil fuels to clean electricity and low-emission fuels like hydrogen.

Alberta chose the third option.

Earlier this year, Premier Danielle Smith released the Emissions Reduction and Energy Development Plan. She tried to pitch it as a climate plan, but don’t be fooled, that’s a fever dream. There is only an “aspiration” (the same weak sauce used by the oil companies) for Alberta to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030.

In fact, Smith has an oil and gas marketing plan, not a climate plan. Investing tens of billions to grow oil and gas supply, while spending more tens of billions to build the 50-year infrastructure to get it to market just as the world embraces your competitor’s product, is a cockamamy business strategy.

You may be surprised to learn that the Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government is fine with that plan. Ottawa has blithely opened the door for expanding liquefied natural gas plants on the West Coast, a particular hobby horse of Smith, even encouraging Alberta and the industry to pursue carbon credits for “clean LNG” sold to Asia where it displaces coal.

The Liberals are also fine with growing oil production, promising that there will not be a production cap to meet emissions goals.

The Liberals are trying to thread the policy needle by pushing oil and gas decarbonization while letting global markets dictate Canadian supply. Policies to date have been mostly carrots. Even the mildest policy sticks provoke vociferous denunciations of “attempts to kill Alberta’s oil and gas” followed by political rage-farming online and in the news media.

No wonder Alberta sees no need to imagine a post-combustion future.

What should Alberta do instead?

To start, Alberta needs to imagine that post-combustion future for its oil and gas sector. There isn’t much effort being expended on this task. Frankly, Alberta and its oil and gas industry are stuck, mired in an incumbency dilemma.

The huge incumbent corporations don’t have an obvious new business model (like legacy automakers, which are rapidly, though painfully, pivoting to electric vehicles). Therefore, they double down on the status quo: frantically cutting costs, demanding public subsidies and policy concessions, and blaming others (including the Trudeau Liberals) for their misfortunes.

The latter strategy effectively hobbles Liberal efforts to push harder for an energy transition strategy within the province.

Nevertheless, Alberta needs Canada to help unstick the conversation about oil and gas extraction and the evolution of a post-combustion economy in the province.

Markham Hislop is a Canadian energy and climate journalist and commentator.

[Top photo: Petroleum can be used for super strong and light carbon fibre, a material key to technologies we’ll need in a low-emissions economy. Photo via Shutterstock.]