Articles Menu

Yesterday I presented the first of two “Am I wrong?” queries regarding the climate crisis. If you accept my facts, I said, you will see the massive challenge we face in transforming human assumptions and ways of living on Earth.

Today I ask:

Question 2: Human nature and our methods of governance are proving incapable of saving the world. We need to ‘get real’ about climate science. Am I wrong?

Remember the self-congratulatory hubbub following “successful” negotiation of the Paris climate accord in 2015? Was all that ebullient optimism justified?

And things are not about to change dramatically. The 2019 Energy Information Administration International Energy Outlook reference case projects global energy consumption to increase 45 per cent by 2050. On the plus side, renewables are projected to grow by more than 150 per cent, but, consistent with the trend I rudely pointed out yesterday, the overall increase in demand for energy is expected to be greater than the total contribution from all renewable sources combined.

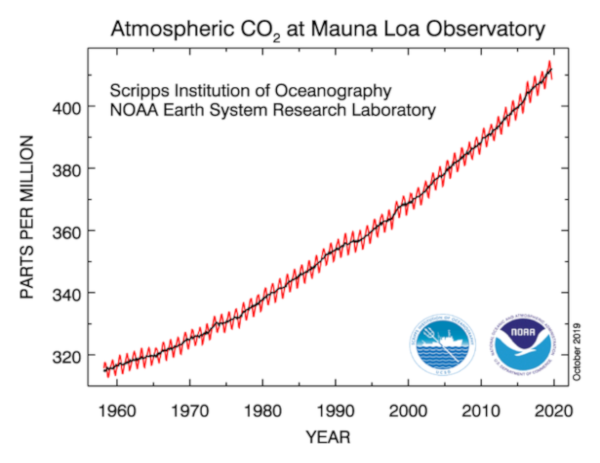

Fact: Without a massive rapid course correction, CO2 emissions will continue to climb. This threatens humanity with ecological and social catastrophe as much of Earth becomes uninhabitable.

Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas increases have already boosted global temperature by approximately 1 Celsius degree, mostly since 1980. Climate scientists tell us that the world is currently on track to experience 3 to 5 Celsius degrees warming. Five-degree warming would be catastrophic, likely fatal to civilized existence. Even a “modest” 3 degrees implies disaster — enough to inundate coastlines, empty megacities, destroy economies and destabilize geopolitics.

Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change therefore committed in 2015 to hold the rise in global average temperatures to “well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.”

But don’t relax just yet. Those commitments made in Paris — the so-called Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs — comprise only a third of the reductions needed to limit warming to 2 degrees. Even if fully met, they put us on track for a potentially catastrophic 3+ Celsius degrees mean global warming.

Systems dynamics confounds the issue. There is a decades-long lag between GHG cause and warming effect because of ocean thermal inertia — the seas absorb 90 per cent of accumulating heat but warm slowly, keeping atmospheric temperatures down. Even if held constant, present GHG concentrations commit the world to an additional 0.3 to 0.8 degrees Celsius warming this century, enough to overshoot the 1.5 degree limit.

There are more reasons to be concerned. Recent analyses suggest that “biogeophysical feedback processes” tied to such processes as permafrost melting, methane hydrate releases and the destruction of tropical and boreal forests may accelerate a cascade of feedbacks pushing the planet irreversibly onto a “Hothouse Earth” pathway.

To meet the Paris challenge of keeping the mean global temperature increase to less than 2 Celsius degrees means cutting CO2 emissions to almost half of 2010 levels and doing so by 2030. It also means completely decarbonizing the economy by 2050.

This, in turn, implies whole-sale transformations of social and physical communities and dramatic changes in material life-styles.

However, as laid out in part one, the current pace of shift away from fossil fuels and lower energy consumption is not remotely adequate. In fact, global energy use and carbon emissions are rising exponentially at the same rate they were four decades ago.

Which presents a conundrum: Reducing fossil fuel use on a vastly sped-up schedule, in the absence of adequate substitutes and a comprehensive wind-down plan, would soon produce some combination of inadequate energy supplies, broken supply lines, reduced production, declining incomes, rising inequality, widespread unemployment, food and other resource shortages, at least local famines, civil unrest, abandoned cities, mass migrations, collapsed economies and geopolitical chaos.

As economists have long recognized, humans are spatial, temporal and social discounters — we naturally favour the here and now, and close relatives and friends, over distant places, merely possible futures and total strangers. Under what circumstances would hundreds of millions of people in scores of countries with disparate political philosophies and political ideologies — people who currently enjoy the “good life” — be induced simultaneously to risk wrecking their comfortable lives to stave off a climate or eco-crisis that many are not convinced is happening and, even if it is, it is perceived likely mainly to affect other people somewhere else?

And keep in mind, the world is committed to accommodating several additional billions who have yet to join the energy-addicted consumer party but are pounding on the door to be let in.

It gets worse. Neoliberal economics is ecologically blind. Even Nobel laureate economists argue that we must maintain allegiance to growth and the illusion of “rescue-by-technology” so the next generation has the wealth and techno-mechanics to mitigate the consequences of climate change. Consistent with this illusory reasoning, many national and corporate leaders interpret the threat of climate chaos as an investment opportunity.

Politically acceptable approaches to reducing carbon emissions discussed at climate talks include technical and organizational capacity-building, wind turbines, various solar technologies, “smart city” infrastructure, electric vehicles, urban rapid transit, yet-to-be-developed carbon capture and storage and other “climate-safe technologies” — i.e., anything that would require major investment and create so-called green jobs (read “further economic growth and profit-making potential”).

Not on the table are ecological tax reform (beyond investment incentives and carbon taxes), structural changes to the economy that would lower consumer demand and reduce energy and material throughput, policies for income/wealth redistribution, major lifestyle changes or strategies to reduce human populations.

Perversely then, policy for climate disaster-avoidance seems designed to serve the capitalist growth economy and make the latter appear as the solution rather than cause of the problem. “Unfortunately,” as University of Vienna public policy professor Clive Spash points out, “many environmental non-governmental organisations have bought into this illogical reasoning.” (Note that many NGOs are dependent on the corporate sector for financial support.)

And this is why the international community — despite the Paris accord, Greta Thunberg, climate strikes and mass public protests — seems determined to stay its growth-driven fossil-fuelled course.

In these circumstances, the world can anticipate more and longer heat waves/droughts, desertification, tropical deforestation, melting permafrost, methane releases, regional water shortages, failing agriculture, regional famines, rising sea levels, the flooding (and eventual loss) of many coastal communities, abandonment of over-heated cities, civil unrest, mass migrations, collapsed economies and possible geopolitical chaos.

Where does Canada fit into all this?

Canada’s Mid-Century Long-Term Low-Greenhouse Gas Development Strategy explores six model approaches supposedly being explored by the federal government to meet Canada’s Paris agreement emissions reductions commitments (net emissions falling 80 per cent from 2005 levels by 2050).

Energy analyst Dave Hughes estimates that, on average, these schemes would require construction of 37,000 two-megawatt wind turbines, 100 Site-C-sized hydroelectric dams and 59 one-gigawatt nuclear reactors. Average cost all in? More than $1.5 trillion.

No such plan is likely ever to be implemented. Instead, Ottawa has bought a pipeline. In fact, both the federal and B.C. governments are firmly on the go-with-carbon team.

Eleven steps

So, where might we go from here? A rational world with a good grasp of reality would have begun articulating a long-term wind-down strategy 20 or 30 years ago. The needed global emergency plan would certainly have included most of the 11 realistic responses to the climate crisis listed below — which, even if implemented today would at least slow the coming unravelling. And no, the currently proposed Green New Deal won’t do it.

Here, then, is what an effective “Green New Deal” might look like:

1. Formal recognition of the end of material growth and the need to reduce the human ecological footprint;

2. Acknowledgement that, as long as we remain in overshoot — exploiting essential ecosystems faster than they can regenerate — sustainable production/consumption means less production/consumption;

3. Recognition of the theoretical and practical difficulties/impossibility of an all-green quantitatively equivalent energy transition;

4. Assistance to communities, families and individuals to facilitate the adoption of sustainable lifestyles (even North Americans lived happily on half the energy per capita in the 1960s that we use today);

5. Identification and implementation of strategies (e.g., taxes, fines) to encourage/force individuals and corporations to eliminate unnecessary fossil fuel use and reduce energy waste (half or more of energy “consumed” is wasted through inefficiencies and carelessness);

6. Programs to retrain the workforce for constructive employment in the new survival economy;

7. Policies to restructure the global and national economies to remain within the remaining “allowable” carbon budget while developing/improving sustainable energy alternatives;

8. Processes to allocate the remaining carbon budget (through rationing, quotas, etc.) fairly to essential uses only, such as food production, space/water heating, inter-urban transportation;

9. Plans to reduce the need for interregional transportation and increase regional resilience by re-localizing essential economic activity (de-globalization);

10. Recognition that equitable sustainability requires fiscal mechanisms for income/wealth redistribution;

11. A global population strategy to enable a smooth descent to the two to three billion that could live comfortably indefinitely within the biophysical means of nature.

“What? A deliberate contraction? That’s not going to happen!” I hear you say. And you are probably correct. It should by now be clear that H. sapiens is not primarily a rational species.

But in being correct you only prove me correct. Disastrous climate change and energy shortages are near certainties in this century and global societal collapse a growing possibility that puts billions at risk.

Now I may be wrong but, if so, please tell me why... Please.

Read the first of this two-parter here. ![]()

William E. Rees is professor emeritus of human ecology and ecological economics at the University of British Columbia.

[Top image: A rational world with a good grasp of reality would have begun articulating a long-term energy and consumption wind-down strategy 20 or 30 years ago.]