Articles Menu

Jan. 14, 2024

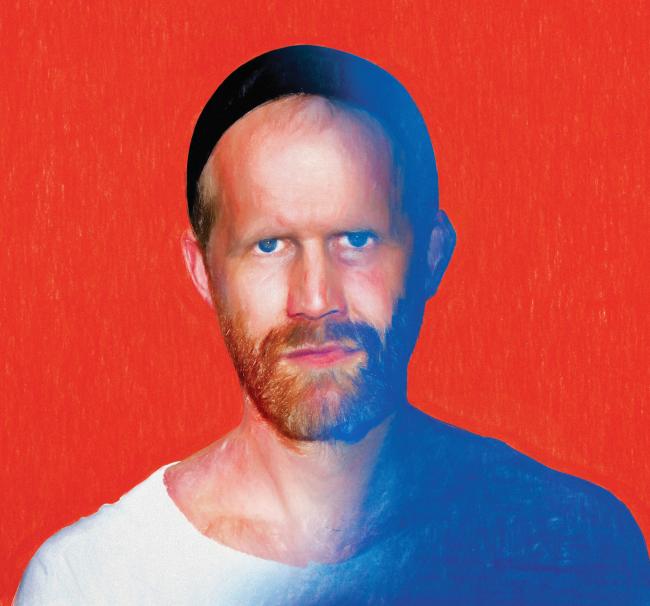

With the 2021 publication of his unsettling book, “How to Blow Up a Pipeline,” Andreas Malm established himself as a leading thinker of climate radicalism. The provocatively titled manifesto, which, to be clear, does not actually provide instructions for destroying anything, functioned both as a question — why has climate activism remained so steadfastly peaceful in the face of minimal results? — and as a call for the escalation of protest tactics like sabotage. The book found an audience far beyond that of texts typically published by relatively obscure Marxist-influenced Swedish academics, earning thoughtful coverage in The New Yorker, The Economist, The Nation, The New Republic and a host of other decidedly nonradical publications, including this one. (In another sign of the book’s presumed popular appeal, it was even adapted into a well-reviewed movie thriller.) Malm’s follow-up, “Overshoot: How the World Surrendered to Climate Breakdown,” written with Wim Carton and scheduled to be published this year, examines the all-consuming pursuit of fossil-fuel profits and what the authors identify as the highly dubious and hugely dangerous new justifications for that pursuit. But, says Malm, who is 46, “the hope is that humanity is not going to let everything go down the drain without putting up a fight.”

It’s hard for me to think of a realm outside of climate where mainstream publications would be engaging with someone, like you, who advocates political violence.1 Why are people open to this conversation?

If you know something about the climate crisis, this means that you are aware of the desperation that people feel. It is quite likely that you feel it yourself. With this desperation comes an openness to the idea that what we’ve done so far isn’t enough. But the logic of the situation fundamentally drives this conversation: All attempts to rein in this problem have failed miserably. Which means that, virtually by definition, we have to try something more than we’ve tried.

How confident are you that when you open the door to political violence, it stays at the level of property and not people? You’ve written about the need to be careful, but the emotions that come with violence are not careful emotions. Political history is replete with movements that have conducted sabotage without taking the next step. But the risk is there. One driver of that risk is that the climate crisis itself is exacerbating all the time. It’s hard-wired to get worse. So people might well get more desperate. Now, in the current situation, in every instance that I know of, climate movements that experiment with sabotage steer clear of deliberately targeting people. We might smash things, which people are doing here and there, 2 but no one is seriously considering that you should get a gun and shoot people. Everyone knows that would be completely disastrous. The point that’s important to make is that the reason that people contemplate escalation is that there are no risk-free options left.

I know you’re saying historically this is not the case, but it’s hard to think that deaths don’t become inevitable if there is more sabotage. Sure, if you have a thousand pipeline explosions per year, if it takes on that extreme scale. But we are some distance from that, unfortunately.

Don’t say “unfortunately.” Well, I want sabotage to happen on a much larger scale than it does now. I can’t guarantee that it won’t come with accidents. But what do I know? I haven’t personally blown up a pipeline, and I can’t foretell the future.

The prospect of even accidental violence against people — But the thing we need to keep in mind is that existing pipelines, new pipelines, new infrastructure for extracting fossil fuels are not potentially, possibly — they are killing people as we speak. The more saturated the atmosphere is with CO2, putting more CO2 into the atmosphere causes more destruction and death. In Libya in September, in the city of Derna, you had thousands of people killed in floods in one night. Scientists could conclude that global warming made these floods 50 times as likely as if there hadn’t been such warming.3 We need to start seeing these people as victims of the violence of the climate crisis. In the light of this, the idea of attacking infrastructure and closing down new pipelines is a disarmament. It’s about taking down a machine that actually kills people.

I’m curious: How do you communicate with your kids 4 about climate? I’m not sure that I’ve had any deliberate plan, but it has been inevitable, with my 9-year-old at least, that we’ve had conversations.

Do you anticipate having the conversation where you explain the radical nature of your ideas? Well, yeah. Both of them have watched the film, “How to Blow Up a Pipeline.”5

Your 4-year-old? Yes. There were a couple of scenes that stayed with them, particularly when people were wounded. They found this fascinating. They know that their father is a little politically crazy, if I can put it that way.

A scene from the film “How to Blow Up a Pipeline,” adapted from Andreas Malm’s book. Neon

Generally we teach kids that violence or breaking people’s things is bad. Do you feel you can honestly give your kids the same message? I hope that I communicate through my parenting that generally you shouldn’t break things. But I hope that they get the impression that I consider there to be exceptions to this rule. My 4-year-old, for instance, when we were biking around Malmo,6 where we live, he would be on the lookout for S.U.V.s. He knows these are the bad cars. I think they have an awareness of the tactic of deflating S.U.V. tires.7

7

Malm was among a group of activists who used this protest tactic in Stockholm in 2007. Deflating S.U.V. tires in protest has not been uncommon in Europe. In 2022, the tires of roughly 900 S.U.V.s were deflated in a single night of coordinated protest, according to the protesters.

Is there not a risk that smashing things would cause a backlash that would actually impede progress on climate? I fundamentally disagree with the idea that there is progress happening and that we might ruin it by escalating. In 2022, we had the largest windfall of profits in the fossil-fuel industry 8 ever. These profits are reinvested into expanded production of fossil fuels. The progress that people talk about is often cast in terms of investment in renewables and expansion in the capacity of solar and wind power around the world. However, that is not a transition. That is an addition of one kind of energy on top of another. It doesn’t matter how many solar panels we build if we also keep building more coal power plants, more oil pipelines, and on that crucial metric there simply is no progress. I struggle to see how anyone could interpret the trends as pointing in the right direction. Now, on the question of what kind of reaction would we get from society if we as a climate movement radicalized: There might be more repression of the movement. There might be more aggressive defense of fossil-fuel interests. We also see signs that radical forms of climate protest alienate popular audiences. But the kind of tactic that mostly pisses people off, and I’m talking about the European context, is random targeting of commuters by means of road blockades. Sabotage of particular installations for fossil-fuel extraction can gain more support from people because these actions make sense. The target is obviously the source of the problem, and it doesn’t necessarily hurt ordinary people in their daily lives. We have to be careful about not doing things that alienate the target audience, which is ordinary working people.

8

For 2022, the Saudi state-controlled Aramco reported a record profit of $161.1 billion; Exxon reported a record profit of $56 billion; BP reported a record profit of nearly $28 billion. (Full 2023 profits have not been reported yet.)

Don’t you think, with companies as wealthy as the oil giants, if activists smash their stuff, they’ll just fix it and get back to business? Here’s a big problem that we deal with quite extensively in the “Overshoot” book: stranded assets. ExxonMobil and Aramco and these giants exude this worry that a transition would destroy their capital and that this shift could happen quickly. So in this context, the rationale of sabotage is to bring home the message to these companies: Yes, your assets are at risk of destruction. When something happens that makes the threat of stranded assets credible, investors will suddenly realize, there’s a real risk that if I invest a lot of money, I might lose everything.

Explain the term “overshoot.” The simplest definition of “overshoot” is that you shoot past the limits that you have set for global warming. So you go over 1.5 or 2 degrees. But the term has come to mean something more in climate science and policy discourse, which is that you can go over and then go back down. So you shoot past 1.5 or 2, but then you return to 1.5 or 2, primarily by means of carbon-dioxide removal. I think this is extremely implausible. But the idea is that you can exceed a temperature limit but respect it at a later point by rolling out technologies for taking it down.

10

Direct air capture, a technology to remove carbon dioxide from the air.

11

Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, the chief executive of ADNOC, who somewhat counterintuitively was president of the recent COP28 climate conference. (Where, it must be said, more than 200 countries agreed to a pact that calls for “transitioning away from fossil fuels.”) Al Jaber was criticized for saying, shortly before COP28, that “there is no science out there, or no scenario out there, that says that the phaseout of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5.”

A few minutes ago, you said you’ve never blown up a pipeline. If that’s what you think is necessary, why haven’t you? I have engaged in as much militant climate activism as I have had access to in my activist communities and contexts. I’ve done things that I can’t tell you or that I wouldn’t tell others publicly. I live my life in Malmo, pretty isolated from activist communities. Let’s put it this way: If I were part of a group where something like blowing up a pipeline was perceived as a tactic that could be useful for our struggle, then I would gladly participate. But this is not where I am in my life.

I don’t want to encourage you, but if people did only the activism that was congruent with where they were at in their life, hardly anybody who lives a comfortable life would do anything. Like I said, I’ve participated in things that I can’t tell you about because they’ve been illegal and they’ve been militant. I’ve done it recently. But I can do that only as part of a collective of people who do something that they have decided on together. We shouldn’t think of activism as something that is invented out of thin air, deduced from abstract principles, and then you just shoot off and do something crazy. I can’t tell you what things I have done, but the things that I do and that any other climate activist should be doing cannot be an individual project.

Greta Thunberg went by herself and sat in front of a building instead of going to school.12

Sure, sure, sure, and she became the person she became thanks to the millions who joined her. Maybe I should do something similar.

In “Overshoot,” you write this about the very wealthy: “There is no escaping the conclusion that the worst mass killers in this rapidly warming world are the billionaires, merely by dint of their lifestyles.” That doesn’t feel like a bathetic overstatement when we live in a world of terrorist violence and Putin turning Ukraine into a charnel house? Why is that a useful way of framing the problem? Precisely for the reason I tried to outline previously, which is that spewing CO2 into the atmosphere at an excessive scale — and when it comes to luxury emissions, it is completely excessive — is an act that leads to the death of people.

But by that logic, unless we live a carbon-neutral lifestyle, we should all be looking in the mirror and saying, I am a killer. I don’t live a zero-carbon lifestyle. No one who lives in a capitalist society can do so. But the people on top, they are the ones who have power when it comes to investment. Are they going to invest the money in fossil fuels or in renewables? The overwhelming decision they make is to invest it in fossil fuels. They belong to a class that shapes the structure, and in their own private consumption habits, they engage in completely extravagant acts of combustion of fossil fuels.13

On the level of private morals: Do I practice what I preach? I try to avoid flying. I don’t have a car. I should be vegan, but I’m just a vegetarian. I’m not claiming to be any climate angel in my private consumption, and that’s problematic. But I don’t think that is the issue — that each of us in the middle strata or working class in advanced capitalist countries, through our private consumption choices, decide what’s going to happen with this society. This is not how it works.

At the protest against the “megabasin” reservoir project in western France last March. Ugo Amez/Sipa, via Associated Press

We live in representative democracies where certain liberties are respected. We vote for the policies and the people we want to represent us. And if we don’t get the things we want, it doesn’t give us license to then say, “We’re now engaging in destructive behavior.” Right? Either we’re against political violence or not. We can’t say we’re for it when it’s something we care about and against it when it’s something we think is wrong. Of course we can. Why not?

That is moral hypocrisy. I disagree.

Why? The idea that if you object to your enemy’s use of a method, you therefore also have to reject your own use of this method would lead to absurd conclusions. The far right is very good at running electoral campaigns. Should we thereby conclude that we shouldn’t run electoral campaigns? This goes for political violence too, unless you’re a pacifist and you reject every form of political violence — that’s a reasonably coherent philosophical position. Slavery was a system of violence. The Haitian revolution was the violent overthrow of that system. It is never the case that you defeat an enemy by renouncing every kind of method that enemy is using.

But I’m specifically thinking about our liberal democracy, however debased it may be. How do you rationalize advocacy for violence within what are supposed to be the ideals of our system? Imagine you have a Trump victory in the next election — doesn’t seem unimaginable — and you get a climate denialist back in charge of the White House and he rolls back whatever good things President Biden has done. What should the climate movement do then? Should it accept this as the outcome of a democratic election and protest in the mildest of forms? Or should it radicalize and consider something like property destruction? I admit that this is a difficult question, but I imagine that a measured response to it would need to take into account how democracy works in a country like the United States and whether allowing fossil-fuel companies to wreck the planet because they profit from it can count as a form of democracy and should therefore be respected.

Could you give me a reason to live?14

What do you mean?

Your work is crushing. But I have optimism about the human project. I’m not an optimist about the human project.

So give me a reason to live. Well, here’s where we enter the virgin territories of metaphysics.

Those are my favorite territories. Wonderful.

I’m not joking. Yeah, I’m not sure that I have the qualifications to give people advice about reasons to live. My daily affective state is one of great despair about the incredible destructive forces at work in this world — not only at the level of climate. What has been going on in the Middle East just adds to this feeling of destructive forces completely out of control. The situation in the world, as far as I can tell, is incredibly bleak. So how do we live with what we know about the climate crisis? Sometimes I think that the meaning of life is to not give up, to keep the resistance going even though the forces stacked against you are overwhelmingly strong. This often requires some kind of religious conviction, because sometimes it seems irrational.

I think all you need to do is look at your children. Yes, but I have to admit to some kind of cognitive dissonance, because, rationally, when you think about children and their future, you have to be dismal. Children are fundamentally a source of joy, and psychologically you want to keep them that way. I try to keep my children in the category of the nonapocalyptic. I’m quite happy to go and swim with my son and be in that moment and not think, Ah, 30 years from now he’s going to lie dead on some inundated beach. You know what I mean?

Which of your arguments are you most unsure of? I cannot claim to have a good explanation for what is essentially a mystery, namely that humanity is allowing the climate catastrophe to spiral on. One of my personal intellectual journeys in recent years has been psychoanalysis. Once you start looking into the psychic dimensions of a problem like the climate crisis, you have to open yourself to the fundamental difficulty in understanding what’s happening.

Is it possible for you to summarize your psychoanalytic understanding of the climate crisis? Not simply, because it’s so complex. On the far right, you see this aggressive defense of cars and fossil fuels that verges on a desire for destruction, which of course is part of Freud’s latent theory of the two categories of drives: eros and thanatos.15

Another fundamental category in the psychic dimension of the climate crisis is denial. Denial is as central to the development of the climate crisis as the greenhouse effect.

What about you, psychoanalytically speaking? I have my weekly therapy on Thursday.

But what’s your deal? You mean in my private life?

Yes. I have to try to figure out how this ties in with my climate activism. I guess this is some sort of a superego part of it: a strong sense of duty or obligation; that I have to try to do what I can to intervene in this situation. That’s a very strong affective mechanism. For instance, I constantly give up on an intellectual project that would be far more satisfying, a nerdy historical project,16 because I feel that I cannot with good conscience do this when the world is on fire.

But I’m asking what caused your impulses. Now we’re into the deep psychoanalytic stuff. I had a vicious Oedipal conflict with my father. One way that this came to express itself was that in the preteen years, I clashed with my father — even more violently during my teenage years. My way to defend myself against what I perceived as his tyranny was to become as proficient as he was in arguing and beat him in his own game by rhetorically defeating him. I think I did. I think he accepted that I’m his superior when it comes to writing and arguing. Psychoanalytically, of course, the things that I’ve continued to do can be understood as an extension of my formative rebellion against my authoritarian father in a classically Oedipal setting, if you see what I mean.17

I asked why you aren’t blowing up pipelines, and you gave this answer about how action has to happen in the context of a community and “Oh, but I have done very serious stuff” — there’s something fishy. You have actually engaged in property destruction? Or are you just scared of somebody calling you a hypocrite? There are things that I have done when it comes to militant activism recently that I, as a matter of principle and political expediency, do not reveal. Part of the whole point of it is to not reveal it. Sure, someone could accuse me of being a hypocrite because I don’t offer evidence that I have done anything militant. But those close to me know. That’s good enough for me.

I also said, “Give me a reason to live.” I will always remember this. No one ever asked me this before.

And I said that one of the reasons to keep going is kids. But you said their future is rationally going to be terrible. If you think your children’s future is going to be terrible, why keep going? One of the arguments in this “Overshoot” book is that the technical possibilities are all there. It’s a matter of the political trends. This feeling that my kids will face a terrible future isn’t based on the idea that it’s impossible to save us by technical means. It’s just, to quote Walter Benjamin, the enemy has never ceased to be victorious18 — and it’s more victorious than ever. That’s how it feels.

Opening illustration: Source photograph by Jeremy Chan/Getty Images

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity from two conversations.

[Top: Illustration by Bráulio Amado]