Articles Menu

October 18, 2019 •

While many Canadians were celebrating Thanksgiving weekend, events in Ecuador generally did not catch media attention. After 11 days of an indigenous-led national general strike and state repression, an agreement was achieved by both parties on the night of October 13th that reversed one aspect of the paquetazo (package) of austerity measures. Those events seem very disconnected with the rhythms of life in Canada, but in many ways there are significant connections. Further, while the general strike has been called off, there is an important need to build or revitalize movements of international solidarity at the contemporary conjuncture.

From October 3rd to 13th tens of thousands of people under the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) organized a national general strike. This action centered on paralyzing the country’s capital, Quito, but protests, blockades, and occupation of public spaces and government buildings occurred across multiple sites in the country. Such an intensive and extensive movement was possible because of the widespread mobilization among the country’s various indigenous nations.

The general strike was called in response to austerity measures taken by the Ecuadorian government as part of conditionalities of signing a $4.2-billion loan with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Government reforms included the removal of subsidies on gasoline prices (Decree 883), that temporary contracts be renewed with a 20% reduction in wages, and public employees be no longer given 30 days of vacation but 15 days. An anti-austerity movement coalesced through the leadership of the CONAIE and brought together student, feminist, environmental justice, and labour movements. In addition, there have been solidarity actions across the world, including La Paz, Buenos Aires, Valencia, Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao, México, Paris, Montreal and New York. Actions in several places included protests outside of the offices of Ecuadorian embassies and consulates.

The Ecuadorian state, under president Lenin Moreno, responded to these protests by declaring a state of exception, which gave significant liberty to the armed forces to repress protesters and censor media critical of the government. From the 3rd to 13th of October, 1192 protesters were detained, 8 were killed, and 1340 injured.1 It has to be remembered that the state repression was unprecedented when considering the immediate past. The previous national indigenous uprisings of 1990, 1994, 1997, and 2000 did not witness such brute force. In the present struggle, this has included the military and police terrorizing indigenous men, women, and children who received refuge in Quito’s universities by throwing tear gas bombs. The armed forces invaded indigenous communal territories in the middle of the night and rounded up their leadership. In multiple cases protesters were beaten, tortured, and trampled upon.

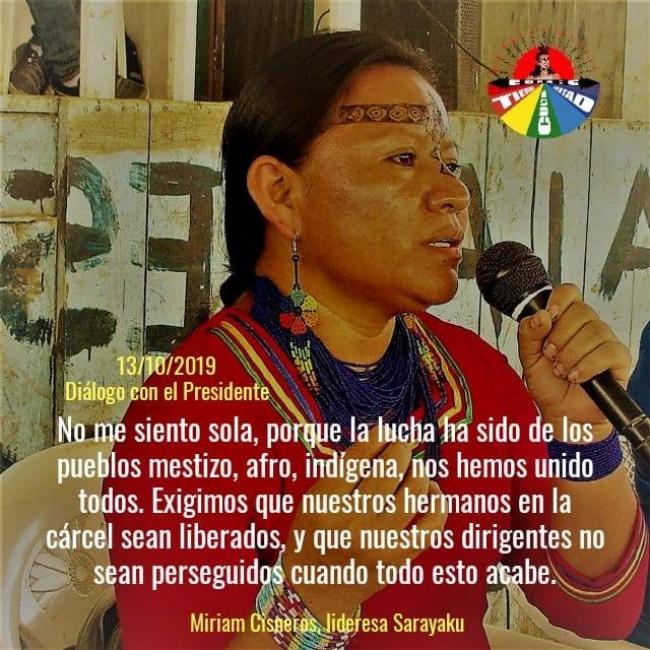

During the dialogue between the CONAIE and the government, Miriam Cisneros, the presidenta of the Sarayaku community in the Amazon, spoke with strength directly to the President:

“Our brothers and sisters have died. This means that our president [of Ecuador] has sent men with arms to kill when we come as a non-violent movement. We have left our children in the jungle [to come to Quito] without knowing that they are eating well. Instead, we have passed 12 days on the streets, Mr. President. […] Our sisters have suffered by being stepped on and beaten by the police and military. Last night when we were staying at the Casa de la Cultura,2 they were not compassionate with us, Mr. President. Doesn’t it hurt you to know that the military and police comes to confront women and children? This is what I have come to tell you as an Amazonica woman, Mr. President. I hope that these assassinations remain in your conscious.”

The power of the general strike was first felt when the government temporarily shifted the seat of its power from Quito to Guayaquil, an important commercial port city that has in the recent past been dominated by conservative forces. And then on October 13th, the government agreed to meet the demand of the CONAIE to remove Decree 883. While much of the Ecuadorian media has focused on the question of the removal of gasoline subsidies for consumers, the CONAIE has emphasized that this movement goes beyond the question of gasoline prices as such.

The national general strike was provoked by IMF conditionalities and this frames the recent direct actions. The movement is confronting how government reforms will further exasperate unequal social relations into the future. On the seventh day of the national general strike the CONIAE wrote:

“The capitalist class sells our homeland and is pro-imperialist, they want to secure the loans of the International Monetary Fund so that their debts and economic crisis is paid by the working class, the indigenous people, and the popular sectors.

“This fight is not only about the conditions of today, nor is it just about the price of gasoline. Our struggle is to prevent that they mortgage our future, such that our next two and three generations will pay with more hunger and poverty for what we didn’t stop today.”3

The neoliberal project represented in the austerity paquetazo is also a colonial project. It is difficult not to think about these actions without remembering that 527 years ago on October 12th was the beginning of colonialism in the Americas.4 Contemporary social stratification is a product of historical processes of organizing society based on racial categories (e.g. white, mestizo, indigenous, black). These processes are still ongoing, but through less explicit mechanisms. During the national general strike, the Ecuadorian government and a section of the white elite and mestizo middle class delegitimized the movement through racist discourse. For example, Jaime Nebot, the mayor of Guayaquil, questioned why indigenous people were invading the cities when their place in society were the highlands (paramo). The general image in Ecuadorian society was that the “indian,” the “savage,” had no place in urban civilized life and their presence was an unnecessary inconvenience.

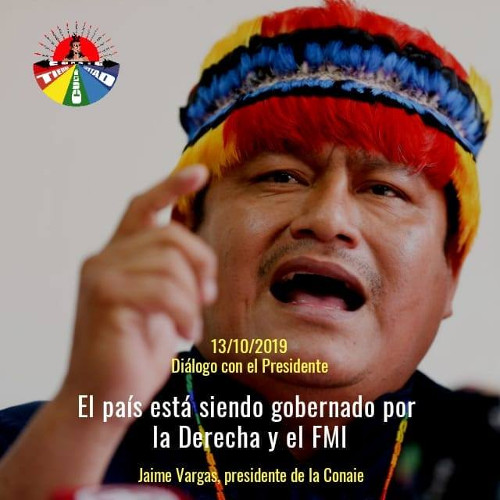

But, the issue is more then just words, as this discourse develops consensus around social organization on the basis of racial hierarchies. Indigenous people’s experience of neoliberalization has been the loss of land and environmental damage through further mining and oil exploration in their territories against their consent. The CONAIE has emphasized that at issue is the liberalization of the economy for the benefit of national and transnational capital that includes the ongoing dispossession of indigenous peoples. During the dialogue process with the government, CONIAE president Jaime Vargas emphasized that “the country is being governed by right-wing forces and the IMF.” All efforts are being made by the current government to maintain the rate of profit of the capitalist class by violently reducing the compensation received for the labour of indigenous people, peasants, and workers. Just as neoliberalization is part of a colonial-capitalist project, this indigenous-led movement against the IMF and the Ecuadorian government is anti-colonial and anti-capitalist.

The CONAIE outlined in a recent report how displacement, dispossession, and exploitation are the mechanisms for violently accumulating more by compensating people less:

“The Government has launched permanent public campaigns to position the so-called ‘benefits’ of mining and extractivism among corporate media, such as El Comercio and Televistazo, and with the support of government institutions. This is all the while advancing the dispossession of the territories and suffering among the population. This includes, but is not limited to the following:

- The imposition of the oil concession of block 28 in the province of Pastaza.

- Conflicts over the start of mining in the subtropical zones of the Cotopaxi and Bolívar provinces, in Intag (on the border between the provinces of Imbabura and Pichincha) and in Río Blanco (Molleturo, Azuay province).

- The beginning of the exploitation phase of mining concessions in the Cordillera del Cóndor and Shuar territory.

- The abuses by the shrimp companies in the area of the Gulf of Guayaquil and on the Puná Island against their workers and against the adjacent communes that were previously stripped of their territories.

- The persecution of labour leaders in the banana sector and the covering up the abuses committed among workers on large landholdings (haciendas).”5

The Moreno government was able to convince international funding institutions to provide Ecuador with a loan by demonstrating that the country was open for mining exploitation by foreign companies. The IMF advised the Ecuadorian government to change their tax regime to favour mining companies.6

Acción Ecológica, an Ecuadorian environmental justice NGO, has argued that:

“The agreement with the IMF implies that the country’s debt will be financed through mining and petroleum exploitation, thus exasperating the extractivist model, aggravated by economic measures that generate greater poverty to the Ecuadorian people and destroying nature.”7

As part of the IMF austerity package, the Ministries of Production and Agriculture announced that import tariffs would be reduced between 50 and 100% for 200 products that include raw materials and capital goods for the agricultural sector. While this appears as providing benefits to small-scale peasants by reducing the cost of agricultural inputs, the reality is that this liberalization only benefits capital-intensive, large-scale, and export-oriented agro-businesses, and transnational agricultural and food corporations. The effect of this measure is that the government is subsidizing capitalist agriculture.8

The indigenous-led anti-austerity movement forced the government to revoke the executive decree removing petroleum subsidies. This is indeed a major victory given that peasants and workers would have otherwise seen an increase in the cost of living. It also reversed a trend that forced working people to pay for the country’s debt and subsidize national and transnational capital. Yet, the other aspects of the austerity paquetazo remain intact. Acción Ecológica has argued that what is behind the austerity measures are the expanding mining, petroleum and agro-business frontiers. They call for struggling against this expansion to get at the root of the austerity project.9

In this sense, the struggle is not over. Indigenous communities in the Amazon continue to resist the expansion of the frontiers of petroleum exploitation. Banana workers continue to fight for better working conditions. The struggle continues since the IMF package enables the continued dispossession and exploitation of working people by national and transnational capital. Given the international connections that are embedded in the IMF package, a corresponding international response of solidarity with the struggles of indigenous people, workers, and peasants is necessary. In the Canadian context, given that the country’s mining companies are significant players in Ecuador and are set to benefit from the IMF package, it is imperative for international solidarity groups in Canada to make these links.

The uncontrolled military force that repressed the national general strike is a signal of the increasing authoritarian character in defense of imperialist interests and capitalist development in the region, from Brazil to Colombia. It should be remembered that the recent authoritarian neoliberal moment builds upon the history of colonialism. That there was little global denunciation of state violence is another reason why movements for international solidarity need to organize. •

Acknowledgments: I want to thank Gladys Calvopiña for feedback and comments. The cited texts are my own translations from Spanish. All errors are my own.

Kasim Tirmizey is a teacher, writer, and activist. He currently teaches at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. He has lived in Ecuador where he was involved with different social organizations including Acción Ecológica.

[Top photo: Photo of Miriam Cisneros, president of the community of Sarayaku. Translation: “I don’t feel alone because this struggle has been alongside the mestizo, afro, and indigenous communities. We have struggled together. We demand that our sisters detained in the prison be liberated, and that our leaders no longer be persecuted when this is over.” Photo Credit: CONAIE.]