Articles Menu

Dec. 29, 2023

Mining companies seeking precious metals under the ocean floor — led by Canadian corporations — are launching a global expedition into uncharted, poorly regulated and risky territory.

Advocates say deep-sea mining would produce a fraction of the carbon emissions of traditional mining. And that it would produce large amounts of nickel, manganese and cobalt, essential for producing electric car batteries.

But critics say the companies are endangering pristine environmental areas and privatizing ocean resources that the public owns. And they note that the companies are well positioned to exploit economically vulnerable countries in the Global South as they seek cheap places to mine.

Who stands to benefit or lose the most?

This summer we travelled to the International Seabed Authority meetings in its headquarters of Kingston, Jamaica. The authority was established under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to manage deep-sea mining. Today, delegates from 168 countries and the European Union decide if projects should go ahead and who should get any royalties.

In conversations with more than a dozen people — experts, mining company representatives, technical experts, environmental NGOs — and on-the-ground coverage in Kingston, we were left with one conclusion.

Private companies have gained the upper hand in international negotiations for contracts to mine the ocean floor. Despite pushback, multinational companies with financial muscle, seeking to mine the deep sea for precious metals, are lobbying their way to advance their interests and seal better deals.

And some have succeeded in turning that advantage into exploration contracts for big chunks of the international seabed reserved for developing countries.

History repeating itself

We’ve been here before. In 2011, Papua New Guinea partnered with Nautilus Minerals, a Vancouver-based company eager to mine the country’s waters. The Solwara 1 project never made money, lost half a billion dollars in investors’ funds and went bankrupt by 2019.

Papua New Guinea’s partnership with Nautilus was ill-advised. Its 30 per cent share resulted in a loss of $120 million, equivalent to nearly a third of the country’s annual health-care budget.

Gerard Barron was one of the main investors of Nautilus. An Australian in his early 40s, he is trying once again to mine the sea floor, this time as CEO of the Metals Co., another B.C.-based startup partnering with tiny island countries like Nauru, Kiribati and Tonga. The goal is to become the first venture to get a licence to exploit deep-sea resources in international waters.

Environmental organizations and local communities in Papua New Guinea warn against a repeat of the costly Nautilus project.

“There are many parallels between TMC [the Metals Co.] and Nautilus Minerals — same founders, same modus operandi. The TMC business plan, like Nautilus’s, is riddled with risks relating to litigation, potential liabilities, lack of insurability, market uncertainty for the metals it plans to mine, and huge questions over technical and financial feasibility,” said Helen Rosenbaum, co-ordinator of the Deep Sea Mining Campaign by the Ocean Foundation.

The difference is that this time the new Canadian player, TMC, has set its focus not on shallow coastlines but on mining the depths of the high seas, a “very lofty ambition,” according to Barron, who is publicly marketed as the Australian Elon Musk.

The specific target is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean, between Hawaii and Mexico. This area borders the exclusive economic zones of the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga. The zone is a deep-sea trench approximately the size of the European Union. It holds an estimated 21 billion tonnes of polymetallic nodules, or what Barron likes to call “batteries in a rock,” alluding to the metals these nodules contain that could potentially power the world’s needed “green transition.” TMC calculates it will get over $30 billion in profits over the 30-year mining project of these little rocks.

Global players and controversial allocations

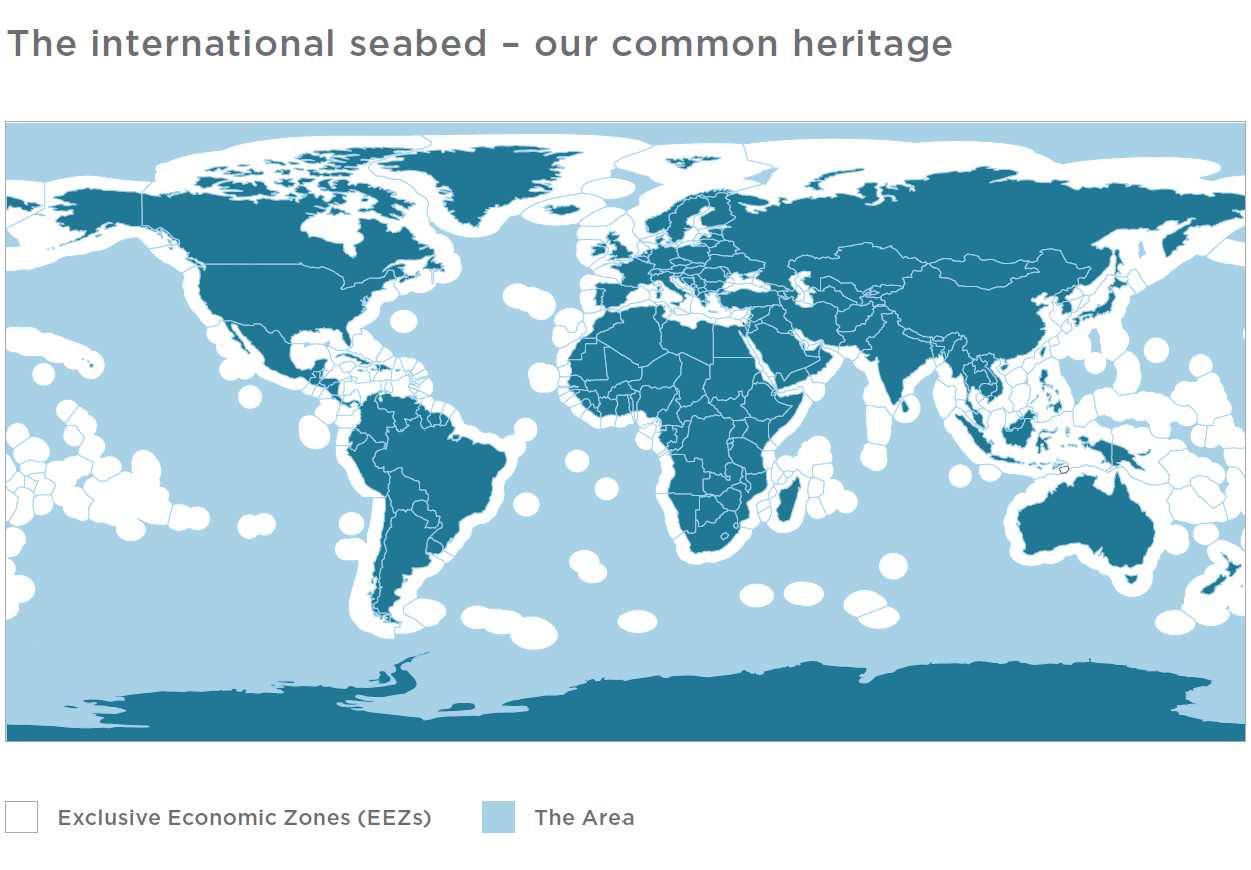

Small and little known by UN standards, the International Seabed Authority has the power to control and govern exploration and mining over half of the Earth, everywhere the deep-sea bed expands across international waters. It holds the keys to the world’s underwater treasures.

Over the past 15 years, the authority has issued more than 30 exploration contracts to companies and their partner nations. Private companies, through their sponsoring states with contracts for exploration, pay the ISA.

The authority has not yet issued a commercial mining licence to any company. But the Metals Co. is inching closer to approval. The Chinese government is just behind TMC, holding five exploration contracts.

To gain access to potentially rich reserves, private companies must navigate a requirement dictated by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This stipulates that the richest portions of the international seabed resources must be set aside for developing countries.

The system of “reserved areas” is supposed to ensure that developing countries have access to deep-sea mineral resources and promote equity. However, the profit-sharing benefit between wealthy players and tiny islands — developing countries — has not been at the centre of the discussions at the ISA.

The authority has given out eight exploration contracts to teams of companies and sponsoring states to explore the richest areas of the deep sea for polymetallic nodules. TMC and its operator partner, Allseas, an offshore construction company based in the Netherlands and registered in Switzerland, control half of them. All together the area TMC can explore is the size of Italy.

A common pattern in these exploration contracts has been the match between wealthy investors, western companies and small developing countries.

TMC partnered with three little Pacific island nations, Nauru, Tonga and Kiribati, to explore the seabeds for metals, promising potential profits for the economically challenged countries. However, details of these agreements are not disclosed.

Jamaica is the latest small island nation to become a sponsoring state to a new contractor, Blue Minerals Jamaica Ltd., which is a subsidiary of Allseas, a company connected to the Swiss Allseas Group and TMC’s operating partner.

Allseas, a family-owned western company, is involved in nearly 50 per cent of the currently approved areas for developing countries. Similar partnerships exist between Global Sea Mineral Resources, a subsidiary of the DEME Group, a Belgian company working with Cook Islands, which holds contracts to 11 per cent of the area.

More than 60 per cent of the current contracts have been set aside for only two western private companies with out-of-the-public-eye agreements with developing countries.

A system ‘open to abuse’

According to experts, this strategy has led to the privatization of significant portions of the seabed under rules that let governments grant access to international seabed areas for mining, with the condition that the benefits be distributed to humankind as a whole.

“It is a system open to abuse,” said Pradeep Singh, an expert on ocean governance and climate policy and a fellow of the Research Institute for Sustainability in Potsdam, Germany.

Andrew Whitmore, finance advocacy officer at the Ocean Foundation’s Deep Sea Mining Campaign, calls it a “cunning ruse.”

“Essentially, it is a link in a chain of people profiting from a resource that should, by its very nature, be considered a global commons,” Whitmore said. “What they’ve done is they’ve created a system that effectively... privatizes it. Individuals are making money off of this backdoor privatization.”

But can these collaborations be advantageous for the developing countries?

Smaller countries do lack the capability to develop the technology and resources needed for such a costly undertaking. They are in a fragile position where they have to rely on external expertise, technology and financial assistance.

The International Seabed Authority governs this process, but researchers argue its effectiveness. It has faced significant criticism for lack of transparency and close ties to corporate interests.

Some ISA meetings have been attended by politicians, company owners and representatives from nearly 200 countries with political and economic interests. Yet the scarcity of journalists at the latest ISA meetings underscores a troubling lack of public oversight.

“It is like to ask the wolf to take care of the sheep,” remarked Sandor Mulsow, a marine geologist who was the authority’s chief environmental officer for five years, in an interview with the Los Angeles Times.

A flawed model

One of the mandates of the ISA is to ensure the exploitation of seabed resources “for the benefit of humankind as a whole.”

But big questions remain unanswered. How will the profits be shared? What are the proposals to make it equitable and beneficial to humankind?

Several delegations have brought up these concerns at ISA meetings. Delegates from Germany and Costa Rica have emphasized the need to substantially raise the payment rates to the ISA from companies.

“It is evident that the current proposals fall short, especially since they do not adequately factor in the environmental costs,” said Singh.

‘A can of worms’

Amidst the many uncertainties, experts are raising concerns about deep-sea mining and whether it can be made beneficial for the wider population, rather than exclusively benefiting a few mining companies.

The ISA’s budget of more than $10 million comes from ISA member states and mining contractors.

As projects are approved, more money in fees and royalties will boost revenues.

And the authority will have to figure out how to cover its operating expenses and provide compensation to land-based mining countries that experience losses due to deep-sea mining, a potential obligation.

All of which will create financial pressures.

“To make the ISA financially viable, it might need to approve a substantial number of mining activities,” said Singh. That could result in pressure to approve risky mining applications, he said.

“It is a can of worms that we don’t want to open.”

Who gets the money?

So far, it’s not clear how much revenue is possible or how it would be shared.

However, recent research under the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Code Project argues that knowing the amount of money to be made from deep-sea mining does matter.

It matters because it helps the countries involved decide how to use that money. It helps people understand whether deep-sea mining will really benefit everyone, as required by international law. Without this information, people might have “unrealistic expectations” about the financial benefits, the paper notes.

The African group of ISA member countries reached a similar conclusion in a joint statement to the ISA in 2019. It concluded the proposed returns to “mankind” and sponsor countries are minimal and unfair.

Singh has seven years focusing on deep-sea mining policy research and participated as an observer at the latest ISA meeting. “If deep-sea mining doesn’t make sense from a benefit-sharing perspective, then it doesn’t make sense to allow it at all,” he said.

The requirement for “equitable benefit-sharing” in Article 140 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea encompasses the fair distribution of not only financial gains but also “other economic benefits.” While the nature of these additional benefits is not explained in detail, some delegates from mining companies — and even the secretary-general of the ISA, Michael Lodge — have previously alluded to a range of potential benefits for “humankind,” with a primary focus on the technology ubiquitous in our daily lives, such as phones, computers or, more distinctively, for those who can drive them, Teslas.

“Everybody in Brooklyn can then say, ‘I don’t want to harm the ocean.’ But they sure want their Teslas,” said Lodge, as reported by the New York Times.

Mining companies affirm deep-sea mining would be more beneficial and less detrimental to our environment than current terrestrial mining practices in places like Indonesia or Congo, often linked with child labour and human rights violations.

Overpromises and opportunism?

Private companies insist they will adhere to law-of-the-sea guidelines, sharing revenues with the Pacific nations sponsoring their endeavours. But the ISA hasn’t yet started the debate about profit sharing.

Rory Usher, TMC spokesperson, said the company doesn’t have the number yet because it has not started production.

Royalties per tonne of minerals, local taxes and substantial investments in host nations are among the ways TMC says it plans to contribute to the local economies in its sponsoring states, such as Nauru.

However, experts mention the information doesn’t need to be publicly available, making it hard to judge fairness.

“We expect to be probably the largest contributor to Nauru economy once we get into first production,” Usher said.

TMC has said that the Nauru and Tonga areas in the Pacific Clarion-Clipperton Zone contain an estimated 1.6 billion tonnes of nodules — enough nickel, copper, cobalt and manganese to electrify 280 million vehicles.

Usher said 90 per cent of its investment is focused on Nauru’s exploration area in the CCZ. Nauru and Kiribati, two phosphate-rich islands, still bear the scars of mining from the colonial era. The two island nations are vulnerable to the impacts of climate change such as rising sea levels, coastal erosion and droughts, and have very few opportunities for economic diversification.

A Greenpeace report found the leading proponents for deep-sea mining in the region are corporate entities that are “geographically, politically and economically removed from the small island nations that will bear the brunt of the consequences.”

Despite companies’ promises, concerns linger. Juan José Alava, principal investigator of the Ocean Pollution Research Unit at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, is skeptical about the returns for the nations.

TMC and other companies will want to make profits after making huge investments in offshore exploration.

“They would like to recoup their investments, so not too much will be given to the people. If at all, they would benefit very little from it,” Alava said.

In 2021, frozen fish was Nauru’s largest export with $123 million in sales. Phosphate was the second-largest export at $31.7 million.

A race for geopolitics

“The U.S. has no voice in these discussions, but we are gonna be severely impacted by the decisions made,” said Uncle Sol, an Indigenous Hawaiian who participated as an observer with Greenpeace at the July ISA meetings in Jamaica.

The U.S. opted not to ratify the treaty law of the sea, which means it is only an observer of the ISA, limiting its influence on shaping deep-sea mining regulations. However, the U.S. does participate as an observer in these discussions and remains a primary focus for lobbying efforts by TMC’s executives.

TMC leadership has been trying to convince American politicians that deep-sea minerals could provide an alternative source for critical minerals. A 2019 report from the U.S. Department of Commerce emphasized the need for the United States to mitigate the risk of dependency on critical mineral sources in countries like China and Russia.

“China’s carefully orchestrated strategy is seeing it catch up fast. At stake is access to the planet’s largest source of energy transition metals. Regulations, as mandated by UNCLOS, are close to being final, and maybe only then the sleepy West will awaken to what’s been on offer. Of course, by then, it’s game over. Sound familiar?” TMC’s Barron wrote on LinkedIn.

Critical minerals play a crucial role in the U.S. economy, affecting various industries such as transportation, defence, aerospace, electronics, energy, agriculture, construction and health care. However, the United States has become more dependent on foreign suppliers for these minerals in the last 60 years, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Uncertain road map for deep-sea mining

After five weeks of intense discussions and growing pressure to “stop deep-sea mining,” delegates to the ISA council — the organization’s 36-member-state policy-making body — agreed that the regulatory framework to start industrial-scale seabed mining is not ready yet. It has now set 2025 as the new deadline for developing mining rules.

The ISA already missed the first deadline for regulations fixed for July 9, and some delegate members already anticipate that the 2025 deadline is unrealistic and not binding.

TMC recently announced that the company intends to submit an application for commercial mining after the ISA meeting in March next year.

A TMC spokesperson stated that the review process would take at least a year. “If everything goes as planned, we are looking at starting the first production around the end of 2024, or the beginning of 2025,” Usher said.

‘No free lunch’

Multiple governments, including those of France, Chile and Vanuatu, and more than 760 scientists and marine experts worldwide have signed a petition calling for a pause or even a ban on deep-sea mining. Their goal is to ensure that environmental, social and economic risks are better understood and that alternatives to deep-sea minerals have been explored before the world decides to “sleepwalk into seabed mining.”

UBC’s Alava wants the precautionary principle to be adopted for deep-sea exploitation, ensuring no work happens before risks are understood and erring on the side of caution.

“I wish we had a pause for the moment to understand the risks on a large scale and the environmental impact, which needs evidence-based decision-making,” he said.

“People need to understand that the mandate of the ISA is to make seabed mining happen,” said one of the delegates at the ISA summit in July. “A mandate that is rather controversial. For some, it is also ‘outdated’ or ‘not fit for purpose.’”

Farah Obaidullah, an ocean advocate and founder of Women4Oceans, says the ISA has an inherent conflict in its mandate.

“On the one hand, to regulate mining — on the other hand, to protect the marine environment. These two are irreconcilable,” said Obaidullah.

“The rules need to change given the reality we are in,” she said, noting the ISA was developed at a time when we were less concerned about climate change, biodiversity and pollution. “We need to think of the deep sea and how it would serve us in the future, in terms of our health and our survival.”

Jeffrey Drazen is a scientist and professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and part of the team of scientists collaborating on the Metals Co.’s environmental assessment of seabed mining.

“Nothing we do as a human society comes without environmental risks,” he said.

Drazen said the core challenge is assessing whether the benefits of obtaining deep-sea mineral resources outweigh the potential harm to our ecosystem, which plays a crucial role in supporting the well-being of our planet. This includes vital functions like carbon sequestration and preservation of biodiversity, both essential for mitigating climate change.

“There is no free lunch; something has to get impacted in some ways,” said Usher.

Alava said the costs are too high. “The economic gains compared to the environmental consequences are incomparable.”

“Economics wins out over nature all the time” reflected Ekolu Lindsey, president of Maui Cultural Lands, an organization dedicated to the preservation of Hawaiian culture.

“It’s very rare that nature gets a win and if it does get a win, that’s because economics is still winning something,” he said.

It remains to be seen who will benefit from the ocean riches, and whether or not they can be effectively utilized for the good of humankind as a whole.

[Top photo: Companies hope to use new technology to mine the ocean floor. Critics wonder about environmental costs and who will benefit. Photo via the Metals Co.]